Journal of Creation 35(3):34–40, December 2021

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Reliable and accessible commentary

A review of: Genesis (Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries) by Andrew E. Steinmann

IVP Academic, 2019

Andrew Steinmann is a Lutheran biblical scholar and currently serves as Distinguished Professor of Theology and Hebrew at Concordia University in Chicago, USA. He has written many scholarly journal articles and a number of books and commentaries on the Bible, including commentaries on Ezra and Nehemiah, Proverbs, and Daniel. This volume on Genesis is part of the Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries series and replaces the original, and now very old (1967), volume by Derek Kidner. As with other updated volumes in the Tyndale Commentary series, this new commentary is much thicker and more detailed than Kidner’s. Moreover, unlike Kidner’s volume, which promoted the day-age view of the Creation Week, Steinmann adopts the traditional literal ‘solar day’ view advocated by Young Earth Creationists (YEC).1

The Tyndale Old Testament Commentary series are designed to be nontechnical and easily accessible commentaries on the English text, aimed at the busy pastor or preaching layman.

The commentary opens with an Introduction to Genesis where the author highlights that this book is the book of beginnings and relates to the beginning of the world, of sin, of God’s promise of redemption and of the nation of Israel, whom God chose as His people.

Authorship

Regarding the authorship, composition, and date of Genesis, Steinmann argues that the Pentateuch (including the book of Genesis) was compiled and edited by Moses. He cites evidence from the Pentateuch itself, the witness of the rest of the Old Testament, the witness of the New Testament, and post-Mosaic additions and glosses in the Pentateuch. However, since Genesis is entirely about events that occurred before Moses was born—the last event in the book, the death of Joseph, took place more than three centuries before Moses’ birth—the case for Mosaic authorship is more vulnerable to challenge than for the other books of the Pentateuch.

Nevertheless, Jesus confidently asserted Moses’ writing of the first book of the Torah. Indeed, John 1:17 says the Law was given through Moses. Jesus is quoted as ascribing the Torah to Moses without dispute or objection from his Jewish opponents (John 7:19–23). This passage assigns to Moses the covenant of circumcision in Genesis 17:1–27.

Documentary hypothesis

Steinmann includes a comprehensive discussion of the so-called ‘Documentary Hypothesis’, which claims Genesis is a patchwork conglomeration of several source texts (Jahwist, Elohist, Deuteronomist, and Priestly sources). He goes on to note the major flaws in this hypothesis. Firstly, the method of identifying the four source documents is highly subjective. The alleged source documents have never been found and there is no historical evidence to indicate they ever existed. In any case, supporters of the hypothesis have never been able to agree among themselves as to the content of each document.

Another weakness of this hypothesis relates to the way it relies on the use of particular vocabulary to distinguish the various source documents. Steinmann rightly notes there are numerous problems with using vocabulary in this way. For example, two passages from different source documents may use similar vocabulary because they are addressing the same subject or describing the same events. In addition, even the use of synonymous terms does not necessarily indicate different traditions. Two words are rarely ever exactly synonymous “and their use may be determined by the different nuances in their denotations or connotations rather than by different authorship” (p. 11). In fact, even words or phrases that are assigned to one source document may appear frequently in another. For example, the term ‘land of Canaan’ is usually a characteristic of P (e.g. Gen. 12:5; 17:8), yet it appears frequently in texts ascribed to both J (e.g. 42:5, 7, 13, 29, 32) and E (e.g. 44:8).

Steinmann points out that the Documentary Hypothesis depends heavily on two popular philosophical developments of the 19th century: the Hegelian philosophy of history and Darwinian notions of evolution. But contemporary historians recognize that the events associated with the historical developments of movements and ideas do not follow any such rigid, prescriptive pattern, and thus, they no longer employ Hegelian historical analysis. In addition, it is not possible to demonstrate that religion evolves in a Darwinian fashion from more primitive forms to more advanced forms.2

Toledot vs colophon

Steinmann also discusses the toledot formula that forms the structural breaks in the text of Genesis. He notes that P.J. Wiseman’s contention that the toledot is a colophon (authorship note) is problematic because each toledot identifier more naturally describes the text that follows rather than the text that precedes. For example, Genesis 25:19 refers to the account of Isaac, but the preceding verses (12–18) list the descendants of Ishmael, whereas the subsequent verses list the descendants of Isaac. Similarly, Genesis 37:2 refers to the account of Jacob, but the preceding verses (36:1–37:1) list the descendants of Esau, whereas the subsequent verses tell the story of Jacob and his descendants.

Genre

Unfortunately, there is no discussion at all on the literary genre of Genesis. Steinmann appears to simply assume the book is historical narrative and processes the text accordingly. This is surprising given that the genre of Genesis has been the subject of much debate with numerous old-earth advocates claiming Genesis 1–2 is poetry, ‘prose-poetry’, analogical, or a literary framework.

Nevertheless, Steinmann is right to note that the focus of the book is continuously being narrowed. Genesis begins with all of creation and ends with the sons of Jacob in Egypt—the beginning of God’s chosen people. The literary structure of Genesis highlights the work of God as more attention is given to the line of Abram/Abraham.

Steinmann also examines the supposed parallels between the biblical creation account and other Near Eastern creation accounts. Regarding the Babylonian Enuma Elish account (figure 1), he points out there are several problems with viewing it as providing the Near Eastern background for the Genesis account. For example, the claimed etymological connection between Tiamat (Akkadian) and tehom (Hebrew) is dubious and controversial. In any case, the most distinctive thing about this account compared to the Genesis account, is the differences rather than the similarities.

Thus, a number of commentators have suggested that the Genesis account is a polemic against Near Eastern creation mythology in general and Egyptian mythology in particular. In other words, the Genesis account serves as a refutation of other ancient Near Eastern creation myths, even though it does not directly reference them.

(Chrono)genealogies

Young-earth creationists routinely argue that because the genealogies in Genesis 5 and Genesis 11 list the age of each ancestor at the time of what appears to be the birth of their descendant, the approximate age of the earth may be calculated by adding these numbers together. However, Steinmann offers a caution in doing this, arguing that the Hebrew words for ‘father’ (ab) and ‘son’ (ben) can at times denote ‘ancestor’ and ‘descendant’, respectively. Moreover, citing the Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, Steinmann points out the verb translated ‘begat’ or ‘became the father of’ (yalad) does not always denote direct fatherhood:

“The word does not necessarily point to the generation immediately following. In Hebrew thought, an individual by the act of giving birth to a child becomes a parent or ancestor of all who are called a son of David and a son of Abraham, yalad marks the beginning of an individual’s relationship to any descendant” (p. 21).

This would mean that, for example, while Seth ‘begat’ Kenan’s ancestor when he was 90 (Gen 5:9), the focus moves to Kenan (5:12–14) as the next major figure only after Enosh’s full life of 905 years (5:11).

To argue his point, Steinmann points to the genealogy of 10 generations from Perez to David in Ruth 4:8–22, where the Hebrew word yalad is also used. In this instance, given that there were 837 years between Perez and David, there had to be more than 10 generations between the two men. It appears that the author of Ruth deliberately omitted some generations so that Boaz would be listed as the honoured seventh person in the genealogy, and David would be the 10th generation.

According to Steinmann, a study of ancient Near Eastern genealogies has shown that genealogies tend to be limited to 10 generations at most, and many are much shorter. For Steinmann, this suggests that these genealogies may skip any number of generations, making it impossible to assume that adding up the years of pre- and post-diluvian ancestors of Abraham will yield the correct number of years from the creation of Adam to the birth of Abraham. Although it is clear that these genealogies sometimes consecutively list father, son, and grandson (e.g. Adam, Seth, and Enosh), Steinmann believes we cannot be certain that this is always the case. But Gerhard Hasel had rebutted this idea years ago, noting:

“The repeated phrase ‘and he fathered PN’ (wayyôled et-PN) appears fifteen times in the OT all of them in Genesis 5 and 11. In two additional instances the names of three sons are provided (Genesis 5:32; 11:26). The same verbal form as in this phrase (i.e. wayyôled) is employed another sixteen times in the phrase ‘and he fathered (other) sons and daughters’ (Genesis 5:4, 7, 10, etc.; 11:11, 13, 17, etc.). Remaining usages of this verbal form in the Hiphil in the book of Genesis reveal that the expression ‘and he fathered’ (wayyôled) is used in the sense of a direct physical offspring (Genesis 5:3; 6:10). A direct physical offspring is evident in each of the remaining usages of the Hiphil of wayyôled, ‘and he fathered’, in the OT (Judges 11:1; 1 Chronicles 8:9; 14:3; 2 Chronicles 11:21; 13:21; 24:3). The same expression reappears twice in the genealogies in 1 Chronicles where the wording ‘and Abraham fathered Isaac’ (1 Chronicles 1:34; cf. 5:37 [6:11]) rules out that the named son is but a distant descendant of the patriarch instead of a direct physical offspring. Thus the phrase ‘and he fathered PN’ in Genesis 5 and 11 cannot mean Adam ‘begat an ancestor of Seth’.”3

God spoke creation into being

Regarding the method of creation, Steinmann highlights that God uses His spoken word to create, and that—unlike other ancient Near Eastern creation accounts—Genesis emphasizes that God alone created the heavens and the earth and everything in them. In addition, Genesis 1 emphasizes that God created in six days. The repeated formula “and there was evening and there was morning, the Xth day” used to describe the creation days is not, as many have claimed, a mere literary feature that is an inconsequential part of a literary framework, but an important and key element of the description of the creation:

“This image of God with his hands in the dirt is remarkable; this is no naive theology, but a statement about the depths to which God has entered into the life of the creation. In contrast to the near Eastern creation accounts, God’s creation was good and perfect, without strife, conflict or contention” (p. 24).

To highlight the orderliness of the creation as opposed to the chaotic process envisaged by the pagan myths, Steinmann argues that Genesis presents the creation over six days as a logical and sequential process organized by God, albeit in a schematic pairing between two sets of three days (Days 1 and 4; Days 2 and 5; Days 3 and 6). Yet he acknowledges that this is only an approximation of what Genesis demonstrates about God’s work, and that the pairings or parallels are partial and incomplete. Indeed, he recognizes that there are connections between pairs of days that do not fit into this scheme. For instance, the lights that God created on Day 4 are placed in the expanse created on Day 2. The sea creatures made on Day 5 inhabit the sea that was made on Day 3. Humans were created on Day 6 to rule over the animals created on Days 5 and 6. Steinmann adds that “it would be a false economy to pit the literary features of the text against its chronological features, as some have attempted.”4

Steinmann rightly acknowledges that the term ‘day’ is not always used the same way, even in the Genesis creation account, but notes that the real question is how to understand the phrases in which ‘day’ is used to demarcate the stages of creation. The creation account contains a variety of temporal terms: ‘beginning’, ‘evening’ and ‘morning’, ‘day’, ‘night’, ‘seasons and days and years’. The meaning of all these temporal terms is shaped by the linguistic context in which they appear. Therefore, Steinmann concludes:

“In the light of this, the term day is used in phrases that designate stages of creation to mark off a single cycle of daylight and night-time. It seems impossible to argue that all of the other terms are used in their usual sense to denote ordinary evenings and mornings, seasons and years, but that day is not … it is a dubious argument to suggest that day means anything other than a single rotation of the earth upon its axis” (p. 27).

Regarding alleged contradictions and inconsistencies between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 that the Documentary Hypothesis implies, Steinmann rightly posits that, rather than being two contradictory creation accounts, these two chapters are complementary. Genesis 2 is clearly not a complete account: the existence of the heavens and the earth is assumed; there is no mention of the sun, moon, and stars; there is no mention of the creation of sea creatures. Therefore, Genesis 2 is actually an expansion or elaboration of the description of the creation of human beings in Genesis 1.

The Fall

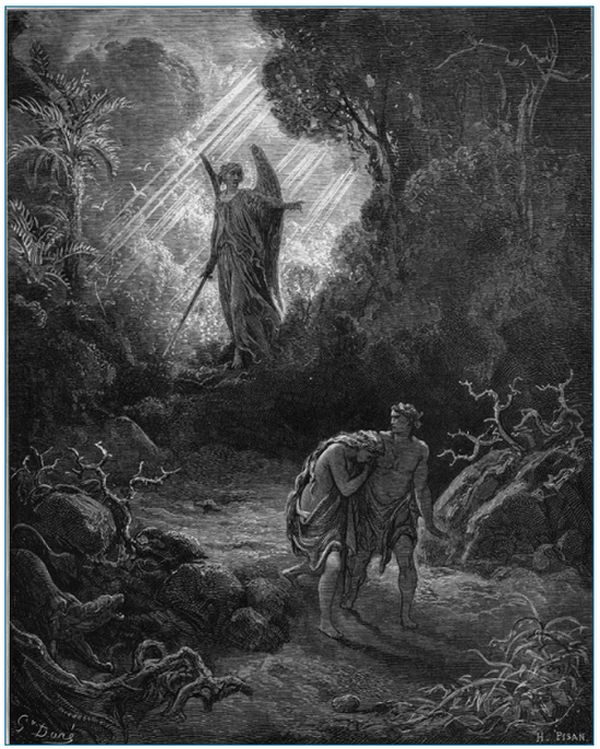

The consequences of the Fall are highlighted throughout the commentary. The first murder is related immediately after humans were expelled from Eden, and several times Genesis directly states that sin had become permanently attached to human nature (6:5; 8:2). The Fall also led to God providing clothing to Adam and Eve (figure 2) at the expense of the life of an animal, given the garments were made from animal skin.

Ultimately, sin led to the great ‘undoing’ of creation—the worldwide Flood at the time of Noah. The land that emerged from the primeval ocean on Day 3 is once again submerged in the waters of the Flood, and then re-emerges afterwards.

Noah is a kind of second Adam, since all subsequent human beings stem from him through his sons. Although Noah was initially judged to be righteous and blameless (Gen 6:9), he also gives in to sin in an echo of the Fall of Adam and Eve (Gen 9:20–27).

Other themes

Steinmann points to the notion of ‘God’s Chosen People’ as a prominent theme throughout the book of Genesis. God chooses his people by favouring a particular line of descendants. God chooses Seth over Cain, Shem over his brothers, Jacob (renamed Israel) over Esau.

‘Justification by faith’ is another important theme and is clearly demonstrated in the life of Abraham. Abraham believed the gracious promise of God that through him and his seed all the nations of the earth would be blessed. Despite Abraham not understanding how this prophecy would be fulfilled through the incarnation and death of Christ, he still trusts in God’s grace and promises: “Abraham believed God, and it was credited to him as righteousness” (Romans 4:3). Indeed, Hebrews 11 also indicates that Abel, Enoch, and Noah were also righteous through faith.

The commentary

Each pericope or section of text is treated with three separate sections: (1) Context, (2) Comment, and (3) Meaning. The Context section discusses the historical and literary context of the particular section of text. The Comment section provides more detailed commentary on the text itself. Though all verses in the text are covered, it is not strictly a verse-by-verse commentary. Given that this commentary is pitched at pastors and laymen rather than other scholars, there is no detailed Hebrew exegesis, though the author does make occasional reference to key Hebrew words and terms, along with clear explanations. Finally, the Meaning section offers a brief summary and meaning of the text, along with any theological notions and implications.

Numerous ‘Additional Notes’ that discuss a particular topic, idea, or interpretation in more detail also appear throughout the commentary. Topics include ‘The seven days of creation’, ‘Knowledge of the name Yahweh in Genesis’, and ‘The ages of the persons in the genealogies of Genesis 5 and 11’.

Given the length of this commentary, I will confine my specific comments to the topics that will most interest the readers of this Journal: Creation and the Flood.

Protoevangelium

On the messianic promise in Genesis 3:15 (aka protoevangelium), rather than being a collective noun, the woman’s ‘seed’ should be taken as singular, given that whenever seed is used with singular verbs and adjectives and especially with singular pronouns it is always singular rather than collective. In this verse, the verb ‘strike’ (shuph; ‘bruise’ in some translations) is singular. Steinmann notes that it is used with a singular pronoun, even though a pronoun is not required by Hebrew syntax in this instance. The superfluous use of the pronoun emphasizes that God is promising a particular seed—a single descendant—of the woman who will crush the serpent’s head.

The word זרֶַע (zera‘) always conveys the concept of a close resemblance between the seed and what produced it. In other words, the descendant is like the ancestor—a human being like Eve—and this keyword zera‘ is used throughout Genesis to refer to the original promise of the Messiah, and the notion is further developed as the story of God’s people is elaborated.

Day 1

Steinmann notes that God is elsewhere identified as the Creator of heaven and earth (Isaiah 40:28; 45:18; Ephesians 3:8–9; Colossians 1:16). Therefore, the first verse (Genesis 1:1) cannot simply be a summary of everything else in the chapter, but must be a statement of the creation of the earth before it was formless and void (1:2). Moreover, for the author of Genesis, God’s existence outside of time and space is simply assumed: God created, but He Himself has no beginning or origin.

Steinmann rightly argues that unless one asserts an unmentioned (and therefore unlikely) gap in time between the creation of the ‘heavens and earth’ and God’s activity beginning in Genesis 1:3, the creation mentioned in verse 1 is part of the activity that is later summed up by verse 5 as ‘one day’. For Steinmann, “In the beginning …” is a statement that “locates the creation of space, matter and time when God, including the person of the Son of God, already was (John 1:1–3; 17:5, 24)”. He rightly rejects the ‘liberal’ and convoluted rendering “When God first created … God said …” and notes that there is little textual support for this.

“Now the Earth …”, in verse 2, focuses the narrative on the—at this point—“formless and void” earth. The ‘deep’ (tĕhôm) signifies the primeval ocean that covers the earth. Steinmann rejects the view that, because tĕhôm shares a common Semitic root with Tiamat (a pagan God), Genesis was derived from, or dependent on, the Enuma elish, the Babylonian pagan creation myth.

In verse 3, “God said …” signifies the power of God “to simply speak things into existence” (cf. 2 Corinthians 4:6; Hebrews 11:3; 2 Peter 3:5). The creation of light precedes the creation of the sun, moon, and stars, and although the source of light is not explicitly stated, the scriptures elsewhere suggest that God himself, the second Person of the Trinity, will be the source (John 1:1–5; Revelation 22:5).

Steinmann argues the first day’s length is summarized by the statement “there was evening and there was morning”, which he contends may be better understood as “In summary, there was evening, then there was morning”. The evening and morning are then said to make one day. He adds that in most Bible versions this is translated as ‘the first day’. “However”, he says, “the Hebrew text contains no article (‘the’), and the number is ‘one’ not ‘first’. The beginning of the day is reckoned from evening. This would dictate the way sacred days were celebrated in Israel (Exo. 12:6; Lev. 23:5, 32; Neh. 13:19)” (p. 52).1

A second day

God divides the waters of the deep and creates the ‘expanse’ (Heb. raqia), which Steinmann identifies as ‘the sky’ (p. 53). He notes that the meaning of the verb form (raqa) is ‘stretch out’ or ‘spread out’ and is used elsewhere of God spreading out the heavens and the earth (Psalm 136:6 Isaiah 42:5; 44:24). The verb is also used in Job 37:18 to describe God’s spreading out the clouds. Thus, Steinmann identifies the expanse as the sky, the upper waters as the clouds, and the waters below as the seas.

However, like many commentators on this part of Genesis 1, Steinmann focuses too much on ‘the waters’ rather than on what was actually created on this day: the expanse!

A fourth day

Steinmann contends that the narrative for the fourth day has a “strong anti-mythological” and “anti-polytheistic” cast to it. “The sun, moon, and stars are creations of the one God, not gods to be worshipped” (p. 54). Indeed, God assigned functions to them (Acts 14:15; 17:24), so they are not self-actualizing and autonomous gods.

The sixth day

Steinmann acknowledges God’s utterance, “Let us create … Our image … Our likeness” has been the subject of much theological discussion. According to Steinmann, a common theory is that this includes the angels or the ‘heavenly court’, despite humans not being depicted as sharing an angelic image anywhere in Scripture. Another theory is that the plural depicts God’s majesty, but this is without grammatical support because the so-called ‘plural of majesty’ does not exist in biblical Hebrew verbs. Another view is that the plural depicts God’s self-deliberation, but this use cannot be demonstrated elsewhere in the Old Testament. However, as Steinmann points out, the text (see the mention of the Spirit in verse 2) clearly depicts God as “an inward plurality and outwardly singular”. Steinmann adds that although this phrasing has been understood to be a reference to the Trinity, the notion of one God in three persons is only implicit here at best.

In any case, although the human beings God creates possess His image, they are not God—as the events of Genesis 3 amply demonstrate. Nevertheless, humans display God’s image by ruling over the animals created on Days 5 and 6.

Steinmann notes that the repeated chronological summary formula “Then there was evening and then there was morning” emphasizes the conclusion of all of God’s creative activity; but in this instance, the definite article precedes the ordinal ‘sixth’, indicating the correct translation as being “a day, the sixth one”.

The seventh day

For Steinmann, the lack of the evening and morning refrain at the end of this day signifies a literary device that sets the seventh day apart and emphasizes its holiness. Indeed, the term ‘the seventh day’ occurs three times in Genesis 2:2–3 to denote three activities of God. Firstly, God completed His work on the seventh day. Secondly, God rested on the seventh day. Steinmann rightly notes that the Hebrew word can mean ‘to cease’ and, in this instance, denotes a cessation of God’s creative work. Finally, God blessed the seventh day and declared it to be holy because on that day He ceased His creative work. And, as Steinmann points out, God did not cease all work, only His creative work.

Interpretations of Genesis

The Framework Hypothesis

Regarding the so-called ‘framework hypothesis’—the view that the days of creation are merely a literary device consisting of two parallel sets of three days, and therefore not intended to be understood literally—Steinmann argues that it draws a false distinction between the literary aspects of the text and its chronological features—as if they are mutually exclusive.5

Analogical Day View

On the Analogical Day View (championed by C. John Collins), Steinmann points out the obvious flaw with this approach: that later references in the Scriptures refer to the events of creation as real and historical. There are no references to the Creation Week being ‘like six days’ followed by a sabbath. Rather, they state that the Israelites are to work for six days and then rest on the sabbath, because God performed His work of creation in six days and then rested on the seventh day (Exodus 20:11; 31:17). Moreover, in these verses the causal relationship runs in the opposite direction to what the advocates’ analogy requires: “the Israelite seven-day working week is compared to God’s work of creation, not vice versa” (p. 60).

Note also that the references to the Sabbath Year make no mention of the Creation Week (Leviticus 25:1–6, 20–22; Deuteronomy 15:1–3; 31:10–13). Yet, if the Creation Week is an analogy, why does it not apply to the sabbath year?

Literal Day View

For Steinmann, Genesis 1 presents a view of creation that is contrary to the primary assumptions and beliefs of other ancient Near Eastern cosmologies from Mesopotamia and Egypt: Genesis is strictly monotheistic rather than polytheistic; and Genesis does not present its actors as autonomous gods, but as subject to the will and power of the Creator. Moreover, that Genesis alone reports God’s creative work occurring over a number of days should not be lightly dismissed.

Steinmann rightly argues that there are compelling reasons for understanding Genesis 1:1–31 to be “depicting six actual, regular days” (p. 61). All six days include the passing of both evening and morning, and the references to days and years on the fourth day (v. 14) clearly refer to literal days and years. The regulations for the sabbath day (Exodus 20:11; 31:17) are based on the pattern of God’s work during Creation Week, without any indication that the creation days are anything other than ordinary days. Thus, Steinmann follows the conclusion of 4th-century Church Father Basil the Great (figure 3):

“And the evening and the morning were one day. Why do Scriptures say ‘one day’ not ‘the first day’? Before speaking to us of the second, the third, and the fourth days, would it not have been more natural to call that one the first which began the series? If it therefore says ‘one day’, it is from a wish to determine the measure of day and night, and to combine the time that they contain. Now twenty-four hours fill up space of one day—we mean of a day and of a night … . It is as though it said: twenty-four hours measure the space of a day, or that, in reality, a day is the time that the heavens starting from one point take to return there. Thus, every time that, in the revolution of the sun, evening and morning occupy the world, their periodical succession never exceeds the space of one day” (pp. 61–62).

Genesis 2

The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil has been the subject of much speculation. But according to Steinmann, the term ‘Good and Evil’ is often used to denote the ability to decide or determine what is acceptable or unacceptable, legally correct or incorrect, and the fruit of this tree probably bestowed the proclivity to depend on oneself rather than God.

On Adam’s need for a helper, Steinmann points out that the word translated ‘helper’ (ezer) does not imply inferiority. Indeed, God is often called a ‘helper’ for humans (Exodus 18:4; Psalm 10:14; 27:9; 40:17; 118:7).

Furthermore, Steinmann emphasizes that marriage is intended to be permanent. Genesis presents marriage as a divine gift to humankind intended to benefit the entire earth with its plants and animals, and thus, “marriage is not merely a humanly devised convention to be changed or adapted to new circumstances or conceptions of human sexuality” (p. 68).

The Curse and Redemption

Steinmann rightly rejects the view that the Fall is some kind of parable or myth, noting that the New Testament treats Adam and Eve as real historical people. Indeed, Jesus, the last Adam, whose life, death, and Resurrection reversed the curse on Adam, is a descendant of the first man, Adam (Luke 3:23–38). And as Paul states, sin came into the world through one man, and death came as a result of sin (Romans 5:12).

Although the curse on the serpent is usually understood as God transforming him to move on his belly, Steinmann points out that the other judgments of God did not transform the basic nature of either the woman or the man. The woman was always the one to bear children through labour and the man was always intended to labour in the fields. Therefore, Steinmann contends that it is unlikely that the Curse transformed the movement of snakes, but, rather, their movement was subjected to futility in that the serpent will now ingest dust—the raw material that was used to make Adam and that will be left as a result of human death.

By restricting their access to the Tree of Life and banishing them from the garden, God prevents humans from living forever in a permanent state of estrangement from their Creator. Since God is the source of life, restricting access to the Tree of Life also restricted access to eternal communion with God. All human beings, even the most pious, are infected by sin and subject to its effects. Yet God promised a “seed of the woman” who would overcome the serpent. The good news is that this seed has already conquered death and overcome evil: through Christ we may have our relationship with God restored (Romans 5:1–2; Ephesians 3:10–12). Therefore, Genesis 3:1–24 is not simply about the effects of sin but also about the love, compassion, and grace of God.

The Flood

Surprisingly, Steinmann makes no explicit statement regarding the extent of the Flood or whether it was local or global. This may be because he believes it was clearly global and there is no need to state the obvious. Indeed, his general comments do indicate a belief in a global Flood.

For instance, Steinmann notes that the last use of the term ‘flood’ occurs with the notice of the rising waters during the 40 days of rain that lifted the Ark to float above the mountains (vv. 17–19). He comments:

“The waters are said to have been 15 cubits above the mountains. Since the Ark was 30 cubits high, this probably indicates that the ark’s draft was 15 cubits (v. 20). Thus, the water rose high enough to lift the ark at least 15 cubits over the highest peak … While the faithful Noah survived with all the life on the Ark, the rest of the world perished (7:21–23). Even the earth’s animals, which are amoral creatures, incapable of sin against God, were affected by the consequences of the tide of sin which had overwhelmed the earth.”

Summary

Steinmann’s commentary is an order of magnitude better than Derek Kidner’s previous volume on Genesis in this series. It contains clear and generally accurate historical and theological explanations of the book of Genesis. This is the purpose and goal of the Tyndale Old Testament Commentary series. Although the author often makes reference to Hebrew words and other ancient Near Eastern cognates, you will not find technical discussions of Hebrew grammar and linguistics. What you will find is a concise, reliable commentary on the text of Genesis that is also accessible to the busy pastor and preaching layman.

References and notes

- Compare Steinmann, A., אֶחדָ as an ordinal number and the meaning of Genesis 1:5, J. Evangelical Theological Society (JETS) 45(4):577–584, 2002. Return to text.

- See Stark, R., Discovering God: The Origins of the great religions and the evolution of belief, HarperOne, New York, 2007. Return to text.

- Hasel, G.F., The meaning of the chronogeneaologies of Genesis 5 and 11, Origins 7(2):67, 1980. Return to text.

- See especially Henri Blocher (In the Beginning, translated by Preston, D.G., IVP, Leicester, 1984) and Meredith Kline (Space and time in the Genesis cosmogony, Perspectives on Science and the Christian Faith 48(1), March 1996). Return to text.

- For a comprehensive rebuttal of this view see Kulikovsky, A.S., A Critique of the Literary Framework view of the days of creation, CRSQ 37(4), March 2001. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.