Egypt and the short Sojourn

Part 1: A biblical analysis

Introduction

The time that the Israelites spent in Egypt (a period of peace and prosperity followed by enslavement) was a significant milestone in the development of the nation of Israel. This is foundational to Christian theology also, because from this new Israelite nation would eventually come the Messiah, who took away the sins of the world (John 1:29). Yet, many people have significant questions about various aspects of this Israelite history. We have tried to answer many of these, including questions about their early history, later history, and genetics. Another huge question deals with how long they were in Egypt.

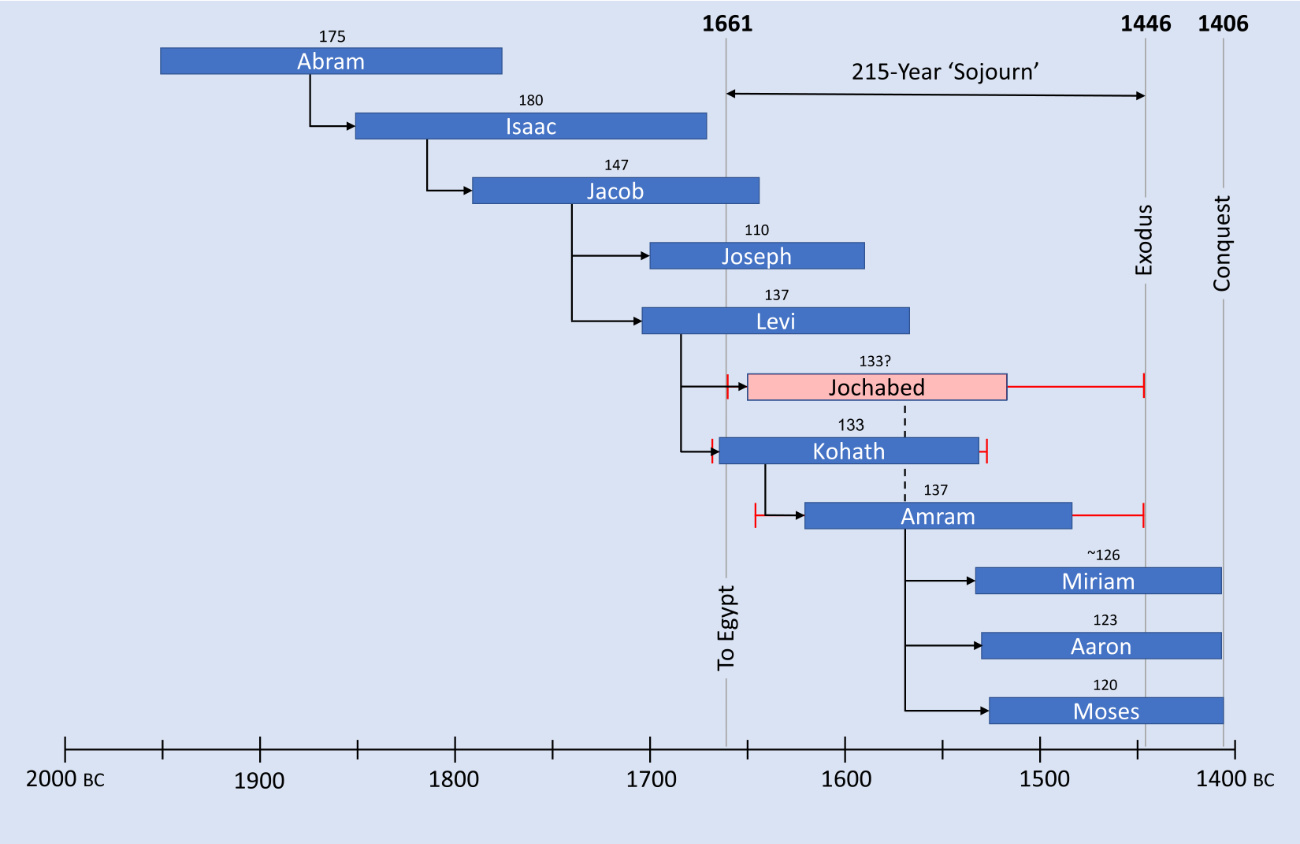

There are two main opinions about the length of the Egyptian Sojourn. It was either 430 years or approximately 215 years, depending on how one interprets and integrates the relevant Scripture passages, and the debate is over 2,000 years old.1 This issue is so complex that it will not be answered in a single article. Yet, as we have studied this issue more and more, we have found ourselves leaning toward the ‘short’ Sojourn. This was not the original position of most people at CMI. Hence, the frequently cited The Biblical Minimum and Maximum Age of the Earth mentions it only for the sake of taking in all views.

The timing of the Exodus is an entirely different question. Many scholars believe the Israelites left Egypt not circa 1446 BC, as a straightforward reading of Scripture would indicate (1 Kings 6:1), but much later, around 1225 BC. This ‘late’ Exodus date is not based on solid biblical data but beliefs about who must be the pharaoh of the Exodus (e.g., that the pharaoh must be a 19th Dynasty Ramesside king). This is because Scripture says that the Israelites were tasked with building the cities of Pithom and Rameses (Exodus 1:11), and in Egyptian history, the name Rameses does not appear until well after 1446 BC. The regnal date of that proposed king is then touted as the Exodus date, even though multiple chronological statements in Scripture contradict this (see Part 2 of this article for more on how Egyptian history aligns with the biblical dates). This article will presume the ‘early’ Exodus date around 1446 BC.

Regarding the short Sojourn, though, it would be far easier to have an extra two centuries to account for the archaeological record of civilizations between the Flood and the Exodus, the population growth of the Israelites in Egypt (assuming several million at the time of the Exodus), etc., but we don’t base our views on convenience. Interestingly, the standard 1446 BC Exodus date is not part of the Sojourn debate. Hence, many scholars like Dr Douglas Petrovich and CMI agree here, even if we disagree over the length of the Sojourn.

First and foremost, CMI is Bible first. Thus, we are going to go with the view that fits (or best fits) a straightforward biblical reading. This requires an examination of the genre, higher-order structures, and internal grammatical constructions. We will also apply several rules that we have used over the years, including the ‘Timothy test’ (developed by Dr Russel Humphries in his book Starlight and Time) and the principle of multiple working hypotheses, with the goal of determining which hypothesis is the strongest among a field of competing ideas.

Many of these ideas appear in other articles, but we wanted to bring everything together so the reader can have all the information available in one place. It also gives us the ability to make changes and updates as we learn more.

Definitions

Before we get into the main discussion, we must make sure everyone is on the same page, so let’s define some terms. The backstory is long, but it can be summarized easily enough. Abraham and his descendants lived in Canaan (modern day Israel and Palestine) for several generations before they were driven out by a great famine. Meanwhile, Abraham’s great-grandson Joseph had been sold by his brothers into slavery in Egypt. When the brothers went to buy grain in Egypt, they learned that Joseph had risen to be second in the kingdom and that he was in charge of famine relief. The whole family, including their father Jacob (a.k.a. Israel), was invited to move to Egypt, which they did. Their time in Egypt is called the Sojourn. After some time, the Israelites fell under bondage. They were miraculously saved and left Egypt in an event called the Exodus.

- Long Sojourn: the view that the Israelites were in Egypt for 430 years, starting with the arrival of Jacob during the famine.

- Short Sojourn: the view that the 430 years also includes the time between God giving the promise to Abraham and Jacob’s arrival in Egypt. In this case, the Israelites were in Egypt for only ~215 years.

- Early Exodus: the view that the Exodus occurred about 1446 BC.

- Late Exodus: the view that the Exodus occurred about 1225 BC.

- AEH: Ancient Egyptian History. This is the secular version of history which must be compared to, and corrected by, biblical history when necessary.

How long was the ‘short’ Sojourn?

Most people assume the short Sojourn was exactly 215 years, but the precise figure depends on which event started the clock and when that event occurred. We also do not know how old Terah was when Abraham was born (Terah was at least 70; Genesis 11:26). We do not know how old Abraham was when he left Haran.2 We do not even know if Terah was dead yet (Genesis 11:32).3 Thus, we have to be very careful when discussing biblical events and their dates. If the Sojourn clock starts with Abraham, we might not be able to pin it down to a specific year.

God makes his first promise to Abram (soon to be renamed Abraham) when he is still in Haran:

Now the Lord said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonors you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Genesis 12:1–3).

Right after this, we get the first statement for the chronology of the short Sojourn:

Abram was seventy-five years old when he departed from Haran (Genesis 12:4b).

But does the sojourn clock start ticking when Abraham is 75, as many assume? Or does it start later? For example, Abram receives another promise at Shechem:

Then the Lord appeared to Abram and said, “To your offspring I will give this land.” So he built there an altar to the Lord, who had appeared to him” (Genesis 12:7).

We do not know when that promise was made. Abram continues to travel south, then goes to Egypt and back (Genesis 12), after which he and Lot separate (Genesis 13). Then God appeared to Abraham again:

The Lord said to Abram, after Lot had separated from him, “Lift up your eyes and look from the place where you are, northward and southward and eastward and westward, for all the land that you see I will give to you and to your offspring forever. I will make your offspring as the dust of the earth, so that if one can count the dust of the earth, your offspring also can be counted. Arise, walk through the length and the breadth of the land, for I will give it to you” (Genesis 13:14–17).

The first promise of ‘four hundred years of affliction’ is made in another undated vision. This important passage marks God’s covenant with Abraham, when the smoking pot and flaming torch passed through Abraham’s sacrifice:

Then the Lord said to Abram, “Know for certain that your offspring will be sojourners in a land that is not theirs and will be servants there, and they will be afflicted for four hundred years. But I will bring judgment on the nation that they serve, and afterward they shall come out with great possessions. As for you, you shall go to your fathers in peace; you shall be buried in a good old age. And they shall come back here in the fourth generation, for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete” (Genesis 15:13–16, emphasis ours).

In that same dream, we read:

On that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram, saying, “To your offspring I give this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates, the land of the Kenites, the Kenizzites, the Kadmonites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Rephaim, the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Girgashites and the Jebusites” (Genesis 15:18–21).

This was done before the birth of Ishmael, when Abraham was 86 years old, and before the covenant of circumcision was enacted, when Abraham was 99 years old (Genesis 17:1) and Ishmael was 13 (Genesis 17:25). Thus, the promise of ‘400 years of affliction’ was made sometime between Abraham’s 75th and 86th year.

Most short-Sojourn advocates start the affliction clock when Abraham is 75, but this is probably not correct. Allowing time for Abraham to travel from Haran, to Shechem, to Bethel, to the Negeb (Genesis 12:8–9), to Egypt, and back to Shechem, means that the “400-year” promise must have occurred well after he left Haran at 75. This means the short Sojourn has to be less than 215 years, but only by a few years.

The ‘215 years’ comes from simple math. Isaac is born when Abraham is 100 years old, 25 years after he left Haran. Jacob is born when Isaac is 60 (Genesis 25:26). Jacob enters Egypt at age 130 (Genesis 47:28). 25 + 60 + 130 = 215 years. This calculation, however, fails to account for several events. The ‘short’ Egyptian Sojourn is probably a little more than 215 years.

When does the ‘430-year’ period start in the short Sojourn view?

We have several contrasting verses that must be addressed. We have already seen that God promised that Abraham’s descendants would be persecuted for “400 years”. Yet, Exodus 12:41 tells us that they left Egypt after “430 years” and “on that very day”.

The time that the people of Israel lived in Egypt was 430 years. At the end of 430 years, on that very day, all the hosts of the Lord went out from the land of Egypt (Exodus 12:40–41).

Note: The Greek Septuagint (LXX) adds “and the land of Canaan” here as follows:

And the sojourning of the children of Israel, while they sojourned in the land of Egypt and the land of Canaan, four hundred and thirty years (emphasis ours).

This follows Exodus 6:4, where God says:

I also established my covenant with them to give them the land of Canaan, the land in which they lived as sojourners.

God said this to Moses prior to the Exodus. Thus, the ‘sojourn’ clock starts before they get to Egypt (e.g., in the time of Abraham). But how can we reconcile the difference between “400” (Genesis 15:13) and “430” (Exodus 12:41) years, and when does the persecution clock start? First, “400” could be a rounded number. But under a short Sojourn, the ‘400-year affliction’ could have started ticking when Ishmael mocked Jacob:

And the child grew and was weaned. And Abraham made a great feast on the day that Isaac was weaned. But Sarah saw the son of Hagar the Egyptian, whom she had borne to Abraham, laughing (Genesis 21:8–9).

If the clock starts ticking when Abraham is about 75, and if Isaac is born when he is 100, and if his weaning happened when he was, say, 5, that totals about 30 years. Hence, the Exodus was 430 years from the time of the promise and 400 years from the start of the persecution.

Of course, as noted above, the promise made to Abraham in Genesis 15 was highly unlikely to have occurred when he was 75. This does not affect the total time, but it does affect the length of the Sojourn. If, say, the promise was made when Abraham was 80, the time in Egypt would be 220 years instead of the often assumed 215 years. This would also mean that the mocking of Isaac did not start the persecution clock. The “400 year” statement would have to be interpreted as a generic timespan of ‘about 400 years’ and could not be used to date the Exodus to a specific year.

It would be understandable to presume that the affliction can only refer to the time of the Hebrews in Egypt, but this cannot be true. Joseph and his extended family initially lived in Egypt under special favour of the pharaoh. If the 400 years of affliction all happened in Egypt, it must have started after the rise of a pharaoh that ‘did not know Joseph’. That is, there was first a time of favour and then a time of affliction. Joseph was about 39 when his family arrived in Egypt (compare Genesis 41:46, 47, 53; 45:6, 11) and he died at 110 (Genesis 50:22). Thus, the Israelites were in Egypt for at least 71 years before the persecution erupted. This has to be added to the total time in Egypt, so the Sojourn would have to be at least 471 years, which cannot be true, for they were in Egypt for 430 years max. This discrepancy is solved in the short Sojourn model, where the 400-years of persecution start prior to the entry into Egypt.

In other words, nobody, whether they believe in the long or short Sojourn, can use the entire time in Egypt as the affliction ‘clock’. A common objection to the short Sojourn is that the Israelites are not under obvious persecution until they arrive in Egypt. Yet, the long Sojourn advocates also have to believe the ‘400 years of affliction’ was not as long as specified.

Under a short Sojourn, the affliction includes Ishmael’s mocking of Isaac, the persecution of Isaac by the Philistines (Genesis 26:17–22), and the persecution of Jacob under Laban. For example, in Genesis 31:42, Jacob says:

If the God of my father, the God of Abraham and the Fear of Isaac, had not been on my side, surely now you would have sent me away empty-handed. God saw my affliction and the labor of my hands and rebuked you last night (emphasis ours).

Supporting evidence

There are many pieces of evidence that support the short Sojourn view. Here are a few.

LXX variant

As mentioned, the LXX translators included the statement “and in the land of Canaan” in Exodus 12:40. They clearly believed in a short Sojourn. Not only that, but the ‘Canaan’ addition is included in several other ancient versions of Exodus (though in some the order of Canaan and Egypt is switched), such as the Samaritan Pentateuch and Dead Sea Scrolls manuscript 4Q14Exod. But the Masoretic text does not contain the longer reading, and it is more trustworthy than these other versions.4 It is possible that this is an exceptional case, in which the Masoretic text lost the original reading. But the short Sojourn view does not depend on this speculative idea. Even if ‘Canaan’ wasn’t in the original Hebrew, these other versions can be understood as attempts to clarify the meaning of the Hebrew. In a lengthy treatise on this issue, researcher Vilis Lietuvietis points out that the Hebrew grammar of Exodus 12:40 in the Masoretic simply emphasizes the completion of the 430-year period, not that the Hebrews were in Egypt for the entire 430 years.5 The text could be translated, “Now the sojourning of the children of Israel, who dwelt in Egypt, was 430 years.” So, either the Septuagint translators added that phrase to clear up a seeming difficulty or they pulled it from some now-lost Hebrew manuscript. Either way, Exodus 12:40 need not contradict the short Sojourn, and this perspective goes back at least to the 3rd century BC.

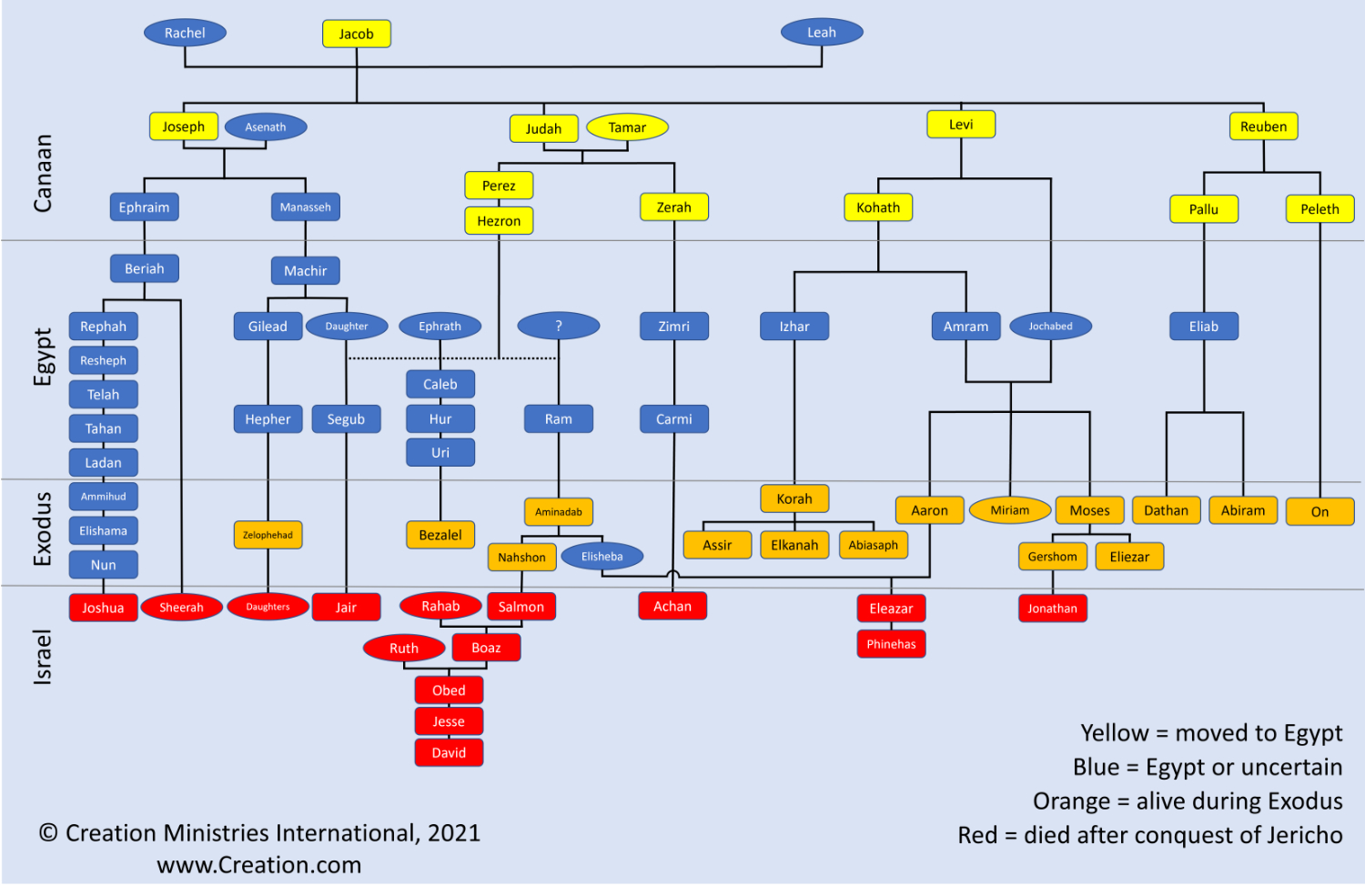

The chronology of Moses’ lineage

The Bible traces Moses’ ancestry from Levi and gives the impression that direct father-son relationships are described with no generational gaps. Some object that other lineages, like Joshua’s, have far more generations in the same amount of time, but this is not unreasonable. In fact, it is expected.6 Also, it would be nigh unto impossible for every lineage that spans the Sojourn to mesh together so perfectly if there were ‘missing generations’.7 It also lists the total lifespans of these men, which places a limit on how long the Hebrews were in Egypt. The math is straightforward:

| Levi begat Kohath before moving to Egypt | (Genesis 46:8, 11; Exodus 6:16; 1 Chronicles 6:1; 23:6) | |

| Kohath lived a total of | 133 years | and begat Amram (Exodus 6:18; 1 Chronicles 23:12) |

| Amram lived a total of | 137 years | and begat Moses (Exodus 6:20; 1 Chronicles 23:13) |

| Moses was | 80 years old | at the time of the Exodus (Exodus 7:7) |

| 350 years | (maximum) | |

Since Kohath and Amram surely didn’t sire these children on the last day of their lives, the time in Egypt had to be significantly less than 350 years. This nicely suits a short Egyptian Sojourn of approximately 215 years, not a long Egyptian Sojourn of 430 years.

New Testament witness

There are three main New Testament passages that impinge on this debate. The first is in the midst of Stephen’s defense in Acts 7:

The God of glory appeared to our father Abraham when he was in Mesopotamia, before he lived in Haran, and said to him, “Go out from your land and from your kindred and go into the land that I will show you.” Then he went out from the land of the Chaldeans and lived in Haran. And after his father died, God removed him from there into this land in which you are now living. Yet he gave him no inheritance in it, not even a foot’s length, but promised to give it to him as a possession and to his offspring after him, though he had no child. And God spoke to this effect—that his offspring would be sojourners in a land belonging to others, who would enslave them and afflict them four hundred years. “But I will judge the nation that they serve,” said God, “and after that they shall come out and worship me in this place.” And he gave him the covenant of circumcision. And so Abraham became the father of Isaac, and circumcised him on the eighth day, and Isaac became the father of Jacob, and Jacob of the twelve patriarchs (Acts 7:2–8, emphasis ours).

Here, we quoted more than just the typical ‘Acts 7:6’ (in bold) so the reader has additional context. It is easy to lift the phrase “enslave them and afflict them 400 years” from the middle of this passage and apply it to the Egyptian Sojourn. The conjoining of ‘enslave’ and ‘afflict’ seems to indicate that the 400-year timespan occurs after the enslavement begins. However, Abraham’s descendants were sojourners in a land belonging to ‘others’ up to the time of the conquest of Canaan under Joshua, e.g., 40 years after the Exodus. Also, as we said above, if the Israelites were afflicted for 400 years in Egypt, the entire Sojourn must have been longer than 430 years, because the affliction does not begin until sometime after the death of Joseph.

The next verse that must be analyzed is nested within Paul’s speech to the synagogue in Pisidian Antioch:

The God of this people Israel chose our fathers and made the people great during their stay in the land of Egypt, and with uplifted arm he led them out of it. And for about forty years he put up with them in the wilderness. And after destroying seven nations in the land of Canaan, he gave them their land as an inheritance. All this took about 450 years. And after that he gave them judges until Samuel the prophet (Acts 13:17–20, emphasis ours).

We now have a third number “about 450”. Is this a round number? A guesstimate? It is neither. Paul has simply summed up the 400-year period, the 40 years of wandering in the desert after the Exodus, and “about” 10 years to complete the conquest of Canaan under Joshua. Either way, we must ask what “all this” is referring to. If it goes back to when “God chose our fathers”, the clock starts ticking when the Fathers (e.g., Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob) were called. “Fathers” is plural, so it is not referring to the call of Jacob alone, although it could be referring to Jacob and his sons. If it starts with the Israelites ‘becoming great’ in Egypt, the clock starts with Jacob. This passage is a bit ambiguous, and by itself may not definitively establish either the long or short Sojourn view.

Yet, the natural reading of Galatians 3:16–17 indicates that Paul believed the clock started ticking with Abraham, not Jacob:

Now the promises were made to Abraham and to his offspring. It does not say, “And to offsprings,” referring to many, but referring to one, “And to your offspring,” who is Christ. This is what I mean: the law, which came 430 years afterward does not annul a covenant previously ratified by God, so as to make the promise void (emphasis ours).

What Paul wrote is Scripture!

Note that Paul would have been familiar with the reading in the Greek LXX and the Hebrew, yet he sure seems to be saying the 430-year Sojourn, the same 430-year period referred to in Exodus 12:41, started with Abraham when he said that the (Mosaic) Law came 430 years after the promise to Abraham. As Scripture is inspired, this passage is the lynchpin for the entire debate and presents great difficulties for a long Sojourn view. We should also keep in mind that the New Testament authors, when citing OT passages, were drawing from the LXX. When Paul says the Law came 430 years after the promise to Abraham, he is unequivocally agreeing with the LXX and is tacitly confirming the insertion made in Exodus 12:40 that the 430 years includes the sojourn in both Canaan and Egypt. Once Paul included this in his writings, it became part of the canon of Scripture. He was a scholar of high reputation and ability (Acts 5:32, 22:3). There is no doubt he could have read Hebrew and Greek. In other words, he must have been completely satisfied that what he was writing was factually accurate. To be a little pedantic, note the ‘and’ in “to Abraham and to his offspring”. Thus, Paul clearly believed the clock started with Abraham, not Jacob. Yet, the primary purpose of this passage is to point people to Christ. Let us not forget that!

Chronographers

The majority of chronographers in the past (e.g., Ussher, Newton) went with a short Sojourn to build their timelines. In fact, the famous “4,004 BC” date from Ussher would not have been possible without a short Sojourn. Likewise, most modern scholarship has gone with the short Sojourn.

Egyptian history

The standard chronology of Ancient Egyptian History (AEH) needs to be condensed because the earliest dates predate Creation and the Flood. But, as we have written elsewhere, it is the earlier parts of AEH where this can be done. The further one goes back, the sketchier the records become, with no archaeological records for some of the alleged kings. See Bates, Egyptian chronology and the Bible—framing the issues.

When starting with a 1446 BC Exodus, there are many ancillary facts in AEH that correspond to a short Sojourn. For example, it would mean that Joseph and his family arrived in Egypt while it was under the rule of Levantine Semites called the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (2IP).

Secular/Standard dating of Egyptian History

Note: These dates are in constant flux.

A dynasty usually refers to a sequence of rulers from the same family or group.

| DATE | PERIOD | DYNASTIES |

|---|---|---|

| Pre 3200 BC | Predynastic/Prehistory | |

| 3200–2686 BC | Early dynastic Period | 1st–2nd |

| 2686–2181 BC | Old Kingdom | 3rd–6th |

| 2181–2055 BC | 1st Intermediate Period | 7th–10th |

| 2055–1650 BC | Middle Kingdom | 11th–12th |

| 1650–1550 BC | 2nd Intermediate Period/Hyksos | 13th(?)–17th |

| 1550–1069 BC | New Kingdom | 18th–20th |

| 1069–664 BC | 3rd Intermediate Period | 21st–25th |

| 664–525 BC | Late Period | 26th |

| 525–332 BC | Achaemenid/Persian Egypt | 27th–31st |

| 332–30 BC | Ptolemaic/Greek Egypt | |

| 30 BC–641 AD | Roman & Byzantine Egypt |

Some brief points follow below. See part 2 for a more detailed explanation on how to synchronize AEH with the Bible.

- Archaeological excavations have revealed another group of Semites that were living under a special status—a kind of state within a state—while under the Hyksos rule of Egypt.

- Joseph rode in a chariot (Genesis 41:43). Chariots were not introduced into Egypt until the 2IP, along with the composite bow. In fact, the ancient Egyptians did not even have a word for ‘chariot’ prior to the Hyksos bringing them to Egypt.

- There are strong indications in Scripture itself that suggest Joseph/Jacob found favour under a non-Egyptian (a.k.a. Hyksos) pharaoh:

- Joseph’s original master was Potiphar, who is continually singled out as ‘the Egyptian’ (e.g., Genesis 39:1). It seems a bit redundant when Joseph is living and working in Egypt, unless Potiphar is also operating under the rule of a non-native (i.e., Hyksos) pharaoh.

- Joseph and his God were lauded for interpreting Pharaoh’s dream (Genesis 41:38). This would be offensive to the polytheistic Egyptian religion.

- Joseph told his father and brothers to tell Pharaoh that he and his sons were shepherds, “… for every shepherd is an abomination to the Egyptians” (Genesis 46:34b). Later, Pharaoh tells Joseph, “And if you know of any talented men among them, put them in charge of my own livestock” (Genesis 47:6). This makes no sense if Joseph’s pharaoh is a native Egyptian.

- Pharaoh gives Joseph ‘the best of the land’ (Genesis 45:18). This is simply an unthinkable thing for an Egyptian pharaoh to cede to foreigners.

- Ahmose, the pharaoh who expelled the Hyksos is a natural candidate for the king “who did not know Joseph” (Exodus 1:8).

- The name ‘Moses’ fits perfectly among the Thutmosid Dynasty names (e.g., Ahmose and his brother Khamose, Thutmose I–IV, etc.). There is no other period in Egyptian history besides the New Kingdom where such names are found in close association.

- After 40 years as an outlaw, God told Moses, “… all the men who were seeking your life are dead” (Exodus 4:19). We are not told how many men were seeking to kill him, or for how long they had been dead, but Pharaoh was among those who sought his life (Exodus 2:15), and he died while Moses was in Midian (Exodus 2:23). The long reign of Thutmose III makes him a natural candidate to have died while Moses was in his 40-year exile. In fact, he is the only pharaoh besides Rameses II to reign for over 40 years during the New Kingdom period of Egypt, although part of that was during his coregency with Hatshepsut. (She is also a candidate for the princess that drew Moses out of the Nile, BTW.)

- The pharaoh of Exodus did not die during the 10th plague. He must not have been a firstborn son. The straightforward timeline places the Exodus during the reign of Amenhotep II, who was not a firstborn son! He was succeeded by Thutmose IV, who was also not a firstborn son, which is important since God told the Exodus pharaoh that He would kill his firstborn (Exodus 4:23). The Dream Stele (that Thutmose IV placed between the paws of the Great Sphinx) confirms that he was not the natural heir to the throne, as would be the case if he had been firstborn.

- There was a dramatic change in foreign policy under Amenhotep II. His father (Thutmose III) conducted possibly 17 military raids into the Levant, establishing vassal states, yet he only brought back 2,214 captives. Amenhotep II conducted only two (three at most) campaigns and brought back over 100,000 people! This dovetails nicely with the depopulation of Goshen and the fact that the Egyptian leaders would need to refill the slave population there. Note: there are Hebrews (Habiru/Apiru) listed among the slaves that were brought back. Also note: this helped depopulate Canaan so that the Israelites had an easier time invading a few decades later.

- There was also a religious change in Egypt after 1446 BC. Amenhotep III (grandson of Amenhotep II and son of Thutmose IV) built the recently discovered Golden City of the Aten. This was dedicated to a single god, Aten, the sun god. His son was born Amenhotep IV but he later changed his name to Akhen aten. This was the famous ‘heretic king’ who worshipped only a single deity—the Aten. The timing of this change is very curious as the leadership of Egypt immediately following the Exodus would have been well aware of the concept of monotheism!

- Many of the Amarna Letters (mainly found in a new city called Akhetaten, meaning “The horizon of the Aten”, built by Pharaoh Akhenaten c. 1346 BC and dedicated to the Aten) are from Canaanite leaders in the vassal city-states that were established by Thutmoses III. They are pleading to Egypt for help because of raids by the marauding Habiru, who are taking over their lands. Their pleas to Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten fall on deaf ears and they cede territory to the marauding Habiru. All this dovetails nicely with the records of the Conquest in Joshua and Judges.

Objections:

Pi-Rameses

They built for Pharaoh store cities, Pithom and Raamses (Exodus 1:11b).

The Hebrew slaves could not have built the city of Rameses some 200 years before the name Rameses was ever in use, and Egypt could not have been called the “land of Rameses” during Joseph’s time when they were given the best of the land. Thus, both the early and late Exodus advocates have an issue with names, and shifting Exodus to the later date does not actually solve the problem.

After the Exodus, the Bible never mentions the name Rameses again. Yet, the city of Rameses was originally called Avaris when it was under the rule of the foreign invaders known as the Hyksos. But the Hyksos were expelled at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty. Over 200 years later, Rameses II expanded Avaris and he renamed the area after himself. How could the Hebrews live in a region and build a city named after someone who was not yet born? Is it possible that the biblical text was updated to reflect a later name?8 We know the biblical books were edited from time to time, including changing spellings and letter forms.9 There are many other passages where this clearly happened. Here are just two.

For example, Keaton Halley wrote:

Genesis 14:14, for instance, mentions Abraham traveling to the city of Dan in order to rescue Lot. Yet the city of Dan was not yet called ‘Dan’ in either Abraham’s time or the time of Moses, who wrote Genesis. The city was formerly called Laish and was not renamed by the tribe of Dan until the period of the Judges, as the Bible itself tells us (Judges 18:29). So the name of the city in Genesis 14:14 was updated well after the time of Moses.8

Cosner and Carter wrote:

Think about it: we know Moses wrote (e.g., Exodus 24:4, Numbers 33:2). But we also know that he could not have written about his own death. Therefore, the books attributed to Moses had to have an editor. We also know that editorial comments (e.g., “to this day”) were sprinkled into the Scriptures and that this was probably from the hand of multiple people. It would be a trivial matter for someone to simply update the name of an Egyptian city so that the people to whom they are writing would understand what was being written.9

There is no evidence that the word “Rameses” was used of any pharaoh prior to its first appearance in Egyptian records in the 19th Dynasty.

If we followed the logic of the late-Exodus arguments, the use of ‘Rameses’ in Genesis 47:11 would place Joseph and Jacob settling in the land in the 18th Dynasty, which essentially no one believes. Rather, Joseph and family settled in the location that later came to be called Rameses, and the city name in this verse was updated to reflect that.

There were too many Israelites at the Exodus

… All the persons belonging to Jacob who came into Egypt, who were his own descendants, not including Jacob’s sons’ wives, were sixty-six persons in all. And the sons of Joseph, who were born to him in Egypt, were two. All the persons of the house of Jacob who came into Egypt were seventy (Genesis 46:26–27).

All the descendants of Jacob were seventy persons; Joseph was already in Egypt (Exodus 1:5).

Only 70 descendants of Jacob went to Egypt (inclusive), yet Exodus 12:37–38 and Numbers 1:46 tell us that about two million left. There is a debate over the term translated ‘thousand’ in these texts, with some saying it refers to smaller units in certain contexts (including these) rather than a literal thousand. Assuming the conservative case, i.e., going from seventy to two million people, was this growth too rapid for 215 years? Some think so.10 Yet, in Modelling biblical human population growth, we showed that, under the right conditions, two million people at the Exodus is not unwarranted. Also, the high fecundity of the Hebrews is mentioned in both Genesis and Exodus. They may have even been more fertile than the Egyptians:

Thus Israel settled in the land of Egypt, in the land of Goshen. And they gained possessions in it, and were fruitful and multiplied greatly (Genesis 47:27).

But the people of Israel were fruitful and increased greatly; they multiplied and grew exceedingly strong, so that the land was filled with them (Exodus 1:7).

But the more they were oppressed, the more they multiplied and the more they spread abroad. And the Egyptians were in dread of the people of Israel (Exodus 1:12).

And the people multiplied and grew very strong (Exodus 1:20b).

There is a parallel argument that, if you consult the genealogical data in Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, etc., you will see that the number of known descendants of any given person does not match the number of people in each tribe. This is especially pronounced when one understands that the genealogies of these people run right through the Sojourn. How can a person have tens of thousands of descendants when only a handful are known to have lived?

Open question: what happened to Jacob’s household when he and his sons went to Egypt? If Abraham had 318 trained men in his house when he went to rescue Lot (Genesis 14:14), he had on the order of 1,000 persons in his household. Isaac inherited that household, as did Jacob. How many people were in Jacob’s house? 10,000?

Consider what the king of the Philistine city of Gerar said to Isaac:

And Abimelech said to Isaac, “Go away from us, for you are much mightier than we” (Genesis 26:16).

How could Isaac, who had but two sons at the time (Genesis 25:19–26), have been mightier than an entire town? Note that Isaac had servants to dig his wells (Genesis 26:25). He is not just a man with a small family and a couple of sheep. Instead, he is a major chieftain in the area, with a large household, who is involved in political power struggles. In the next generation, this much larger household went to Egypt. Seventy descendants of Jacob (inclusive) were among them.

These people would have married into the main family over time. Being that all the males were circumcised (after Abraham was 99 years old, Genesis 17), they were family, friends, and kin and they shared the same religion.

You shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskins, and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and you. He who is eight days old among you shall be circumcised. Every male throughout your generations, whether born in your house or bought with your money from any foreigner who is not of your offspring, both he who is born in your house and he who is bought with your money, shall surely be circumcised. So shall my covenant be in your flesh an everlasting covenant. Any uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin shall be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant (Genesis 17:11–14).

And all the men of his house, those born in the house and those bought with money from a foreigner, were circumcised with him (Genesis 17:27).

Did Jacob leave these people, who were included in the covenant, to die in a famine when he took his sons to Egypt? Consider:

So Israel took his journey with all that he had … (Genesis 46:1a).

Clearly not. Thus, more than 70 people entered Egypt. These people would have swelled the numbers listed in each tribe at the Exodus.

Note also that the brothers were married before they went to Egypt (Benjamin already had 10 sons!). The wives are not numbered. There was also a “mixed multitude that went up with them” when they left Egypt (Exodus 12:38).

We must understand that ‘descendants’ does not equal ‘tribe’ and that there was a lot of marriage between Israelites and non-Israelites over time. If a woman from outside marries in, and if her family was already living among one specific tribe, that family would be counted as part of the tribe, especially if the males are already circumcised. Thus, the numerous household servants would have married into the main families over time. Indeed, a man from Judah who had no sons allowed his Egyptian servant to marry one of his daughters and ten generations of descendants (~300 years!) are listed (1 Chronicles 2:34–41). Since this is recorded in a section talking about people in the time of David, one assumes the event took place about 300 years earlier, e.g., around the time of the Exodus. Given a pre-Sojourn household of several thousand people and several generations of intermarriage, one would not expect the number of people in each tribe at the Exodus to equal the number of direct descendants of the 12 Israelite patriarchs. Far from it, in fact.

Joseph in the Middle Kingdom?

Some suggest that the Genesis account seems to indicate a Middle Kingdom arrival time for Joseph. That is, a few aspects do not seem to fit into the 2IP. For example, when Pharaoh commanded that Joseph be taken out of prison, Joseph shaved himself before appearing to Pharaoh (“…they quickly brought him out of the pit. And when he had shaved himself and changed his clothes…“, Genesis 41:14). Being that the Egyptians were fastidious about shaving all body hair (one presumes this was to keep down lice and other pests), and being that we have images of the Hyksos with facial hair, this is seen as a direct reference to an Egyptian cultural setting. However, the Hyksos quickly ‘went native‘, as so many conquering cultures have done (especially in Egypt) over time. That is, they adopted the pharaonic and priestly system because it was an efficient way to run the country and to keep the local population happy. Thus, Joseph shaving does not necessarily equate to an Egyptian-specific culture. One would also presume that Joseph would need a good clean up after having spent several years in a prison. The text does not say that he completely shaved his head, face, and body as the Egyptians did, so we are left with some ambiguity.

The second issue that might speak to a Middle Kingdom setting is that Pharaoh had Joseph marry the daughter of the priest of On (a.k.a. Heliopolis to the Greeks). The temple to Re (the sun god) in On was one of the most important temples in Egypt. If the pharaoh was Hyksos, why did he not marry Joseph off to a daughter of the priest of Set, the favorite god of the Hyksos? First, the objection is presuming too much about which priest had an available daughter! Second, what if a particular woman had caught Joseph‘s attention and he had asked Pharaoh to do a favour for his favorite servant? Third, Joseph was second-in-command over all Egypt, so he had more freedom than anyone save Pharaoh himself. Fourth, assuming that all marriages at this level were arranged for political purposes, having the daughter of the most important priest in Egypt marry a foreigner had strong political and social ramifications. This could have been done to denigrate the priest or to bring the temple further under the influence of the Hyksos.

Conclusions

The length of the Sojourn has been hotly debated for a long time due to seemingly conflicting Scriptural passages. Yet, most scholars have sided with the ‘short’ Sojourn position. There are good reasons for this, but it takes some thinking and digging to find all the points of correspondence. We understand that many of us have just accepted the ‘430 years in Egypt’ given to us through church and secular culture such as popular movies. This includes the authors of this article. We trust, though, that you will see our heart in this. As a biblical apologetics ministry, we want to support the Bible, no matter what. Yet, as a ministry that focuses on Genesis, we have a mandate to explore every topic that impinges on the age of the earth. Interestingly, the Sojourn question is one of those things. We cannot date Creation without knowing how long the Israelites were in Egypt! After we started this line of inquiry, we discovered many ways in which Egyptian history matches the short Sojourn. This was quite unexpected, but also very exciting as it helped us more fully develop our biblical model of Egypt. Please continue reading as we present the reasons why Egyptian History aligns strongly with a short Sojourn. We also reveal our best candidates for the mysterious unnamed pharaohs in the book of Exodus. Please read part 2.

References and notes

- E.g., see Minge, B., ‘Short’ sojourn comes up short, J. Creation 21(3):62–64, 2007, and the subsequent replies. Return to text.

- Hardy, C. and Carter, R., The biblical minimum and maximum age of the earth, J. Creation 28(2):89–96, 2014. Return to text.

- Sibley, A., Was Terah dead when Abraham left Haran? Views on the meaning of Acts 7:4, J. Creation 31(2):78–83, 2017. Return to text.

- Sanders, L. and Carter, R., Is the Septuagint a superior text for the Genesis genealogies? creation.com, 25 Sep 2018. Return to text.

- Lietuvietis, V.I., Was the Masoretic Text’s Ex. 12:40 430 years sojourn to the Exodus begun by Abraham or Jacob? 7 May 2020; preprint doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.27734.06728. Return to text.

- See figure 8 in Carter, R., Patriarchal drive in the early post-Flood population, J. Creation 33(1):110–118, 2019. Return to text.

- Carter, R. and Sanders, L., How long were the Israelites in Egypt? Using their own family tree to resolve a debate, creation.com, 21 Sep 2021. Return to text.

- Halley, K., Exodus evidence revisited, creation.com, 18 June 2022. Return to text.

- Sanders, L. and Carter, R. The inspiration of Scripture comes in various forms, creation.com, 10 Sep 2019. Return to text.

- E.g., see Minge, ref 1. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.