The Namblong people: ‘We need to know where we come from!’

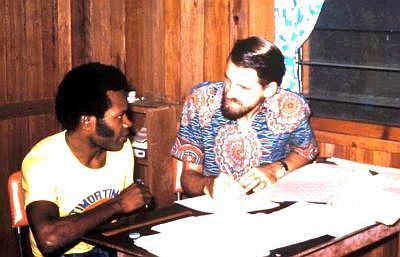

The people of Papua rebuked this SIL translator for wanting to postpone translation of Genesis 5

Kevin May, an Australian member of Wycliffe Bible Translators, served with the Summer Institute of Linguistics as translator for the Namblong people of Papua from 1978 to 1985. There was much that he and his wife Wendy learnt from them during that time. In this article, Kevin tells of a key factor that was crucial to the Scriptures’ relevance to the people.

In 1985 I was working with my language helper, Tomas,1 on translating the Scriptures for the Namblong people of the Indonesian province of Papua. We had completed some selected passages outlining the life of Christ, and then began on the beginning chapters of Genesis.

In chapter 5 we were working on verses that follow a regular pattern—each descendant of Adam was x years old when he had a son, and lived for y years after that and died at the age of (x + y). As this was repetitive and relatively uninteresting to me, I thought I would postpone it. I said to Tomas, ‘Let’s leave these for now, and I’ll be able to fill in the details later on.’

But Tomas was unhappy. He looked at me earnestly, and said, ‘You can’t do that! We must do it all now. We need to know where we come from!’ So we took the time to translate every verse, and Tomas was happy.

Among Namblong people, as in many similar people groups (for example, the Binumarien people2), relationships are at the heart of society. Each must know how he relates to everyone else so that he can behave appropriately. Younger people must respect those who are older, and special duties apply to particular relationships, especially how you relate to your mother’s clan—and conversely to your sisters’ children. Several times even I was asked whose ancestor was the elder one, mine or theirs. It was vital information that would tell the people how they should relate to me, a Westerner.

Tomas’ statement has a wider application than just among Namblong society. We all need to know where we come from, because meaning depends on origin. The difference it makes is extreme.

If we are mere products of chance, random processes, then life has no intrinsic meaning. Our thoughts are just the inescapable result of our brain chemistry, and we are no better than the victims of a cruel joke—or, as Prof. Dawkins has said, of “blind, pitiless indifference”.3

But if we are beings made in the image of God, able to be creative and to communicate4 with others, then life is full of meaning. God made us for the purpose of fellowship with himself, and he is delighted when we communicate with him, love him, and love one another.

How blessed we are to know that the latter is true! Knowing God as our great creator, and living daily in his presence, makes life meaningful and worthwhile. We have the greatest thing in all the world—Life with a capital L! We have purpose in living, and even beyond that, we know where we are going.

Reference

- May, K., Is Genesis myth or reality? Creation 17(3):22–23, 1995; creation.com/gen-myth. Return to text.

- Walker, T., How the Binumarien people of New Guinea discovered Jesus is real, 2012; creation.com/binumarien. Return to text.

- Dawkins, R., River out of Eden, Chapter 4, Weidenfeld and Nicolswi, 1995. Return to text.

- May, K., Born to communicate, Creation 31(2):40–42, 2009; creation.com/born-to-communicate. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.