Oxford-trained scientist acknowledges the Creator

Dominic Statham interviews biophysicist Dr Yusdi Santoso

Dr Yusdi Santoso grew up in Bali, a province of Indonesia known for its beautiful mountains, stunning coastal regions and rich cultural heritage. Following high school, he moved to Singapore to study Computer Engineering at Nanyang Technological University (NTU). Yusdi then worked for a company specializing in bioinformatics, producing software which helps biologists study DNA. He became deeply interested in molecular biology and particularly the area of biophysics. In 2005 he was accepted as a Ph.D. student by the Department of Physics at Oxford University in the UK, funded by a scholarship from NTU. Much of his time at Oxford was spent studying DNA polymerase, one of the remarkable nanomachines found in the cells of our bodies. (See box). Yusdi now works in business and software consulting, and is married with two young children.

Raised in a Roman Catholic family, he attended a Catholic high school in Malang, East Java; however, he says he did not know God personally at this time. While studying in Singapore, his wife-to-be (Jessica) encouraged him to attend her Bible-believing church. Yusdi told me, “I came to see the Bible as the Word of God, and Christianity began to make sense. Prior to this, my life was compartmentalized and I couldn’t relate what I was taught about God to everyday life. I was ‘religious’, in that I went through the motions, going to church because it was a cultural expectation. I came to see the Bible as God’s revelation of Himself, which transcended any teaching of men. By reading it, I began to understand what God wants from us, and with this, God’s peace came into my life.” Yusdi told me that the books of the Bible he treasures most are Romans and Hebrews, “because they present the Gospel in such a logical way.”

Being a predominantly Muslim country, the creation/evolution debate does not have the same prominence in Indonesia as it does in much of the West. Yusdi had been taught Darwin’s theory of evolution at school, but as one view of origins, rather than as scientific fact. He remarked, “Actually, I didn’t really think about evolution very much until going to Oxford.” In the first year of his Ph.D., he was required to complete several courses covering the background biology needed for his research projects. The preliminary reading list included Richard Dawkins’ book, The Blind Watchmaker, which argues that life does not require a designer. “In the first week of lectures my professor told us that, if you are a biblical creationist, this course is not for you! Because of my confidence in the Bible I knew he was wrong, but I was not equipped to respond to his arguments.”

The church Yusdi attended in Oxford, however, taught biblical creation and he told me that he was helped much by John Ashton’s book, In Six Days,1 in which 50 Ph.D. scientists explain why they accept the Bible’s account of origins rather than evolution. “I particularly appreciated the scientific depth of the arguments presented.”

In Yusdi’s view, the greatest difficulty with the theory of evolution is its improbability. “The strength of evolution,” he said, “is in the narration—it’s a good story. However, when you look at the details it seems most unlikely.” He pointed out that several prominent scientists have concluded that it is very, very improbable that life could have arisen on earth all by itself. Evolutionist Francis Crick, one of the discoverers of the structure of DNA, admitted, “An honest man, armed with all the knowledge available to us now, could only state that in some sense, the origin of life appears at the moment to be almost a miracle, so many are the conditions which would have had to have been satisfied to get it going.”2

Yusdi continued, “Darwin’s theory is not measurable or testable. It’s also too vague to be of any use. There are so many moving pieces in the evolution story and you can fit any data into it. A good scientific theory provides a framework which enables scientists to make predictions about how things behave, and has explanatory power. Evolution is not like this.”

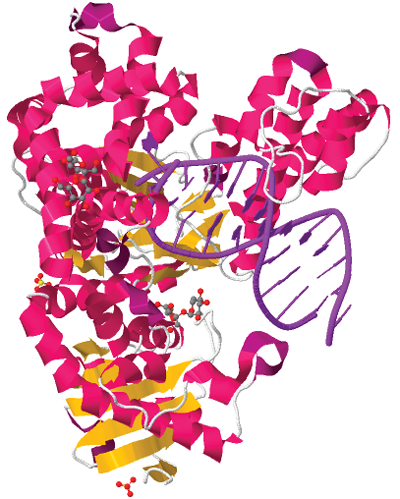

Yusdi spent three years studying DNA polymerase, a tiny machine used by the cell to copy DNA. When cells divide (make copies of themselves) the daughter cell requires its own copy of the original cell’s DNA, and this is produced by the DNA polymerase.

Could DNA polymerase have evolved? Yusdi replied, “None of my colleagues at Oxford can explain how a machine like this could have arisen through an evolutionary process.” The popular view among his colleagues, he said, is that life began by RNA molecules forming self-reproducing systems—the ‘RNA world hypothesis’. However, he said, “nobody can show, in a way that’s at all convincing, how a DNA polymerase machine made up of proteins could have evolved from RNA—and this would seem impossible to me.”

Yusdi explained that, according to the theory of evolution, less complex types of DNA polymerase (as in bacteria, e.g.) evolved into more complex types (e.g. as in humans). However, the difference, he said, between the DNA polymerase of a bacterium and that of a human is like that between a bicycle and a car (or perhaps even a bicycle and a factory) and we don’t find intermediate forms. “It is very difficult to see how this evolution could have happened. Indeed, it is impossible even to conceive of a series of steps that could produce one type from another. The intermediate forms would not function as well as the original forms, so they would be out-competed. The evolutionary explanations are just too simplistic and they ignore the details. To evolve a bicycle into a motorbike by adding an engine is a very big step, because engines are complex and need to be carefully designed. Similarly the differences between the different types of DNA polymerase would require much detailed design work at each stage.” To Yusdi, the strongest evidence for creation is the argument from design because, to him, living things are so well designed.

I asked Yusdi whether he came across Professor Richard Dawkins while he was studying at Oxford. He replied, “I saw him around the campus from time to time, but did not get to speak with him. His books are quite well thought of, but he is not regarded any more highly than other professors at the university. He is seen more as a popular science writer rather than a serious scientist. Some people would remark that his passionate stance against creationism, and even his apparent hatred of God, seemed incongruent with his claim to be unbiased and scientific.”3

Yusdi told me that, in the final year of his Ph.D., he realized that his belief in creation would lead to him being marginalized at work. Consequently, he pursued a career in business and software consulting, rather than science. He explained, “In many parts of the world, the scientific community discriminates against those who do not toe the party line on evolution. For example, it would have been very difficult for me to obtain funding for my work.” Despite this, Yusdi encourages young Christians to study science so that they can defend the faith and the creation worldview. However, he believes it wise for students to obtain their degrees first, before openly arguing for the biblical position. Moreover, he said, “Studying science enabled me to do something worthwhile. For example, my discoveries were a step towards a greater understanding of DNA replication which could lead to the curing of some genetic disorders.”

Yusdi is adamant that the reality of God can be seen in creation: “The Bible tells us that we are fearfully and wonderfully made (Psalm 139:14) and I saw this very clearly in much of my scientific work. My research into DNA polymerase, particularly, showed me just how complex life is. All this speaks of an awesome Creator.”

What is DNA polymerase?

DNA polymerase is an enzyme, a protein ‘machine’ that makes copies of DNA molecules. It is found in all living organisms in various levels of complexity and performs a number of important functions. For example, our bodies are constantly producing new cells and each one requires its own copy of our DNA. This is produced by the DNA polymerase. This amazing molecular machine is also used to repair damaged DNA and in copying DNA for the purposes of reproduction. Forensic scientists use DNA polymerase taken from bacteria to produce copies of human DNA for ‘genetic finger-printing’. DNA needs these machines to copy itself, but it also codes the instructions to build its own copying machines. But these instructions to build copying machines can’t be passed on unless copying machines are already present.

DNA is made up of two strands zipped together and wound into a double helix. Before being copied, it must be unwound and unzipped, which is accomplished by another protein machine called a ‘helicase’. The process is very fast and the helicase spins the DNA molecules at the speed of a jet engine. If we were to magnify a typical DNA polymerase machine taken from a bacterium, so that it occupied the same space as a kitchen food mixer, the new DNA strand would be generated at a rate of around 20 km/hour.

It is most important that the DNA polymerase copies the original molecules accurately, as otherwise the information carried by the copy will be corrupted, potentially leading to genetic diseases, birth defects or even cancer. This is achieved in a number of ways, including the use of a proof-reading system whereby the DNA polymerase checks the copy as it’s produced and cuts out any mistakes. Human DNA polymerase makes less than one mistake in a billion bases (letters). This is equivalent to misspelling one character when you copy the content of one thousand Bibles.

Yusdi’s research led to the discovery that, prior to proof-reading, there is an additional process that screens the DNA ‘letters’ before they are incorporated into the copy.1 Since defective screening leads to copying errors, Yusdi’s work may contribute to the curing of genetic disorders arising from inefficiencies in this process.

Reference

- Santoso, Y., et al., Conformational transitions in DNA polymerase I revealed by single-molecule FRET, PNAS 107(2):715–720, 12 January 2010 | doi:10.1073/pnas.0910909107.

References and notes

- Ashton, J.F. (ed.), In Six Days, Master Books, Arizona, USA, January 2001, available creation.com/store. Return to text.

- Crick, F., Life Itself: Its Origin and Nature, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1981, p. 88. Return to text.

- Until his retirement in 2008, Richard Dawkins was Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.