When God rescued King Hezekiah, part 3

Archaeology confirms the biblical account—Jerusalem’s deliverance and Sennacherib’s end

Parts 1 and 2 of this series covered many archaeological finds consistent with Assyria’s invasion of Judah in 701 BC, as recorded in 2 Kings 18–19. In this concluding article, we turn to the evidence supportive of the fact that God kept His promise to spare Hezekiah and the city of Jerusalem. We also see how the people of Judah continued to endure and recover after the devastation wrought by Assyrian king Sennacherib.

Jerusalem miraculously spared

It would be fair to say that Sennacherib did achieve many of his goals in his campaign against Judah. He turned back the combined forces of Egypt and Cush. He devastated many Judahite cities. He returned power to several pro-Assyrian vassal kings. He received a hefty tribute from Hezekiah. Yet Hezekiah himself and his capital city survived without having to fight a battle there—just as Isaiah had predicted. Although Sennacherib did boast in his annals about trapping Hezekiah inside Jerusalem, he said nothing about destroying or defeating that city. In fact, Sennacherib did not even besiege the city as some older translations of the Assyrian texts claimed. Rather, the terminology Sennacherib used speaks merely of a blockade.1 Sennacherib could only claim, “I confined him [Hezekiah] inside the city Jerusalem, his royal city, like a bird in a cage.”2

The Bible gives us a fuller picture of why Jerusalem was not taken. It is obvious why Sennacherib would not want to publicize the rest of the story.

And that night the angel of the Lord went out and struck down 185,000 in the camp of the Assyrians. And when people arose early in the morning, behold, these were all dead bodies. Then Sennacherib king of Assyria departed and went home and lived at Nineveh. (2 Kings 19:35–36)

While this miraculous defeat is not mentioned in the Assyrian records, the fact that Sennacherib did not include any rhetoric about a complete triumph over Jerusalem could be seen as tacit testimony to the authenticity of this biblical miracle. Admittedly, some historians think this is overstating things. They argue that Sennacherib had no intention of capturing Jerusalem and only meant to restore order, being satisfied with Hezekiah’s submission and tribute payment. On the other hand, A.R. Millard argues that it was “unusual” for Sennacherib not to depose Hezekiah. He writes,

Rebels had to be punished, that was the purpose of Sennacherib’s campaign. … For the majority that was disgrace and captivity or death … If they tried to resist, their cities were besieged, captured, and despoiled … the booty being carried off to Nineveh.3

Millard mentions that there were some exceptions, where Assyrian kings showed mercy, but he says that Hezekiah’s case still violates the normal pattern in many respects. For example, Millard points out,

Sennacherib encircles Jerusalem with watchtowers,[ref.] yet does not press a siege. This contrasts with his action against the other towns of Judah …

Jerusalem did not suffer that fate. Yet Sennacherib’s sparing of the city is not expressed in his campaign records. There is … no announcement ‘Hezekiah the Judean came out of Jerusalem and brought his daughters to be my servants, together with his son. I had mercy on him and replaced him on his throne. A tribute heavier than before I imposed upon him.’ Nothing hints at the Assyrians entering the city. …

[T]he tribute was paid, not to Sennacherib at Lachish or at Libnah or outside Jerusalem, but later; ‘after me’, says Sennacherib, ‘he sent to Nineveh my royal city’. The rebel ruler … was left on his throne, left in his intact city, required only to pay tribute. Hezekiah was treated lightly in comparison with many. …

Further, the note of triumph with which the reports of Assyrian campaigns normally end is absent from this one. True, the list of Hezekiah’s tribute has a note of success, yet it is muted in comparison with the ending of every other one of Sennacherib’s campaigns in which he proclaims what he had done. …

For whatever reason the reliefs of Lachish were carved, the fact remains that they were the ones to be set prominently in a room to themselves rather than reliefs portraying the surrender of the capital, Jerusalem, or the tribute of its king, Hezekiah.4

In sum, Sennacherib’s lack of emphasis on Jerusalem makes perfect sense if the biblical account is true. Whether or not he desired to take further action against Hezekiah, the evidence we have is consistent with the biblical record. Though Judah suffered great losses, God spared Jerusalem. Hezekiah remained on the throne, and Sennacherib returned home to Nineveh.

Sennacherib’s demise

Some time afterward, the Bible records that Sennacherib was murdered by his own sons.

And as he was worshiping in the house of Nisroch his god, Adrammelech and Sharezer, his sons, struck him down with the sword and escaped into the land of Ararat. And Esarhaddon his son reigned in his place. (2 Kings 19:37)

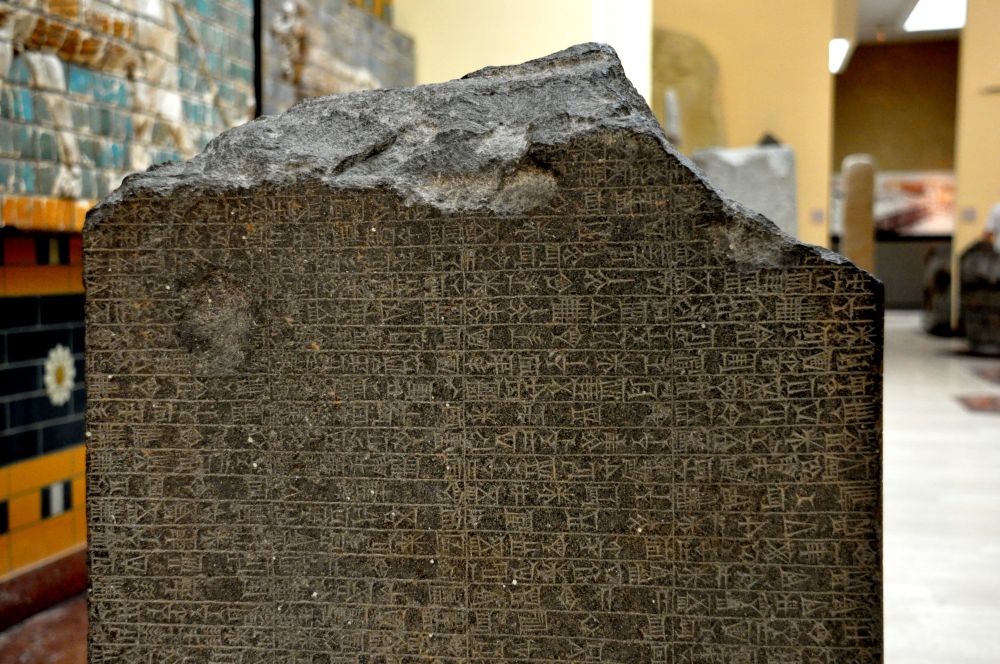

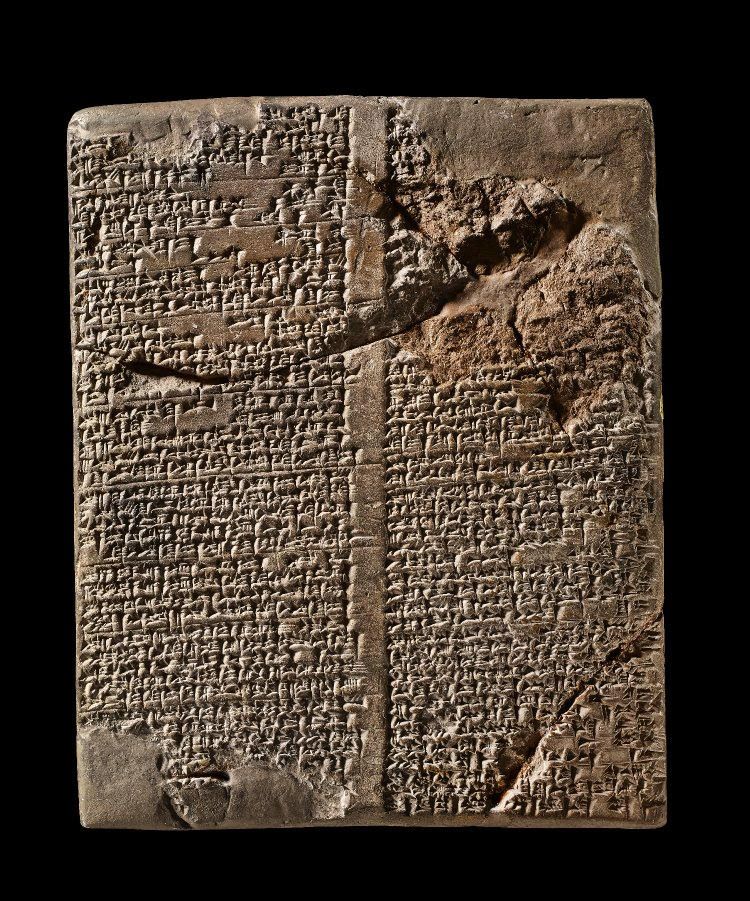

Several ancient documents confirm that Sennacherib was slain by at least one son. The Istanbul Stele of Nabonidus (figure 3.1), for example, testifies that, “The king of Subartu [i.e., Assyria] … his son—the offspring of his heart—struck him down.”5 Similarly, the Babylonian Chronicle of Nabonassar (figure 3.2) casually mentions that, “On the twentieth day of the month Tebêtu, Sennacherib, king of Assyria, was killed by his son in a rebellion.”6 Most significantly, the Assyrian document Letter to Sennacherib Concerning Conspiracy (figure 3.3) describes an attempt to alert Sennacherib of plans by his son to kill him, and it names the son as Arda-Mulissi. This is the Assyrian equivalent of the biblical form, Adrammelech.7

The reason for the conspiracy appears to be related to Sennacherib’s appointment of a successor. Esarhaddon, whom Sennacherib designated as the crown prince, was his youngest son, so perhaps the older brothers did not take kindly to being passed over. In a prism made by Esarhaddon after he became king (figure 3.4), he describes how his brothers opposed him and how he prevailed.

Afterwards, my brothers went out of their minds and did everything that is displeasing to the gods and mankind, and they plotted evil, girt (their) weapons, and in Nineveh, without the gods, they butted each other like kids for (the right to) exercise kingship. …

Moreover, those rebels, the ones engaged in revolt and rebellion, when they heard of the advance of my campaign, they deserted the army they relied on and fled to an unknown land.8

Though the murder of his father, Sennacherib, is not explicitly mentioned by Esarhaddon, the violent hostility of his brothers and the flight of the rebel leaders to a distant land coincides well with the biblical text. So, once again, in all these details the Bible is well supported by the available historical evidence.

God’s faithfulness and the remnant of Jerusalem

Sennacherib may have been proud of all his conquests and military achievements, but God through Isaiah told Sennacherib that he was only a tool in the hands of a sovereign Lord.

Have you not heard that I determined it long ago? I planned from days of old what now I bring to pass, that you should turn fortified cities into heaps of ruins, … (2 Kings 19:25)

This same sovereign God promised to preserve and protect a remnant of survivors in Jerusalem. Isaiah prophesied that the people would be growing their own crops and reaping a harvest in three years, and that, without needing to sow seed in the meantime, they would have food to sustain them (2 Kings 19:29). After this, the remnant would begin to flourish.

And the surviving remnant of the house of Judah shall again take root downward and bear fruit upward. For out of Jerusalem shall go a remnant, and out of Mount Zion a band of survivors. The zeal of the Lord will do this. (2 Kings 19:30–31)

Archaeology broadly supports these claims as well. After the devastation wrought by Sennacherib, Judah did not return to its former glory. The nation was certainly downsized and only a remnant of the people remained, including many who sought shelter in Jerusalem. Yet rebuilding began to occur in the 7th century BC, and God remained faithful to His people, causing them to endure. The God of Israel continued to demonstrate the truths acknowledged by Hezekiah when he pleaded in prayer for deliverance.

O Lord, the God of Israel, enthroned above the cherubim, you are the God, you alone, of all the kingdoms of the earth; you have made heaven and earth. … Truly, O Lord, the kings of Assyria have laid waste the nations and their lands and have cast their gods into the fire, for they were not gods, but the work of men’s hands, wood and stone. Therefore they were destroyed. So now, O Lord our God, save us, please, … that all the kingdoms of the earth may know that you, O Lord, are God alone. (2 Kings 19:15–19)

Conclusion

Given that over 2,700 years have transpired since these events, it is remarkable that archaeological remains corroborate the Bible to the extent that they do. But this should not be so surprising to those who, like Hezekiah, continue to trust in the Lord today. Despite the strong aversion to ‘biblical archaeology’ displayed by many contemporary scholars, the Scriptures have a long history of reliably guiding archaeologists to truth, and they are regularly backed up by archaeological finds. In fact, the Bible has a delightful habit of being exonerated by discoveries that overturn the claims of its critics. Where apparent discrepancies or questions remain, we can take comfort from the fact that much of the Bible’s history has already been clearly confirmed. As the episode between Hezekiah and Sennacherib helps to illustrate, our trust in the Bible as a reliable text is well placed. It is, after all, the very Word of God.

Assyrian army destroyed by rodent-based plague?

Oftentimes, modern references to Sennacherib’s defeat at Jerusalem associate it with a rapidly spreading plague introduced into the Assyrian camp by mice. For example, a 2018 article in Haaretz was titled, “How mice may have saved Jerusalem 2,700 years ago from the terrifying Assyrians.”9 Did mice or plague have anything to do with the biblical event?

Unlike the account of the Philistine capture of the Ark of the Covenant, in which mice play a central role (1 Samuel 5–6), the Bible does not explicitly mention any rodents or illnesses in connection with this event. It says that “the angel of the Lord” was responsible for decimating the Assyrian army in a single night (2 Kings 19:35). The claim that mice and disease were involved comes from an attempt to harmonize the Bible with several other ancient witnesses.

For example, the Greek historian Herodotus, who lived in the fifth century BC, recorded an occasion in which field mice supposedly gnawed the quivers, bows and shield handles of Sennacherib’s soldiers, leaving them unarmed for battle the following day, when many were killed.10 According to Herodotus, however, this happened at Pelusium in Egypt rather than near Jerusalem, and the warriors were killed as they fled, not in their sleep. Admittedly, the Bible is not explicit about where the Assyrians were decimated, but a question mark remains as to whether Herodotus and the Bible are even referring to the same event.

The other witness is Josephus, writing in the first century AD. In his Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus refers to Herodotus’ account of the mice gnawing through the Assyrian weaponry at Pelusium, but he actually differentiates this from the encounter at Jerusalem.11 He says the mice first brought about an Assyrian retreat in Egypt and then, upon returning to Jerusalem, Sennacherib found a plague devastating the army he had left there with the Rabshakeh.

Many contemporary writers suggest that each of these stories is based upon the same event, but perhaps corrupted in the details and given a theological spin. The historical core to the story, they surmise, could have been a mice-borne plague which broke out in the Assyrian army, forcing a retreat. But this is speculative, and rooted in a mindset that demands a naturalistic explanation for everything.

While it is possible that the angel could have used mice or plague as his means, the support for this conclusion is weak. It is certainly clear that not all of the details of these stories can be reconciled. So, either they refer to different occasions or some of the details were distorted during transmission in the extra-biblical records. But, given that the Bible is the Word of God, it is the account we can trust. Hezekiah was indeed rescued by supernatural intervention, whether the angel used intermediaries or not.

References and notes

- Elayi, J., Sennacherib, King of Assyria, p. 76, SBL Press, Atlanta, GA, 2018. Return to text.

- Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period (RINAP) 3, Sennacherib Chicago/Taylor Prism, 3:27–28. Return to text.

- Millard, A.R., Sennacherib’s Attack on Hezekiah, Tyndale Bulletin 36:69, 1985. Return to text.

- Millard, A.R., Sennacherib’s Attack on Hezekiah, Tyndale Bulletin 36:70–72, 1985. Return to text.

- My composite translation from: Cogan, M., Sennacherib and the Angry Gods of Babylon and Israel, Israel Exploration Journal 59(2):167–168, 2009 and Mitchell, T.C., The Bible in the British Museum, p. 74, Paulist Press, Mahwah, NJ, 2004. Return to text.

- ABC 1.iii (From Nabû-Nasir to Šamaš-šuma-ukin), Livius.org. This same document also confirms Sennacherib’s succession by Esarhaddon. Return to text.

- Parpola, S., The Murderer of Sennacherib, in Alster, B. (ed.), Death in Mesopotamia, RAI 26, Akademisk, Copenhagen, 1980. Return to text.

- RINAP 4, Esarhaddon Nineveh Prism A, 1:40–84. Return to text.

- Bohstrom, P., How mice may have saved Jerusalem 2,700 years ago from the terrifying Assyrians, Haaretz, 18 April 2018. Return to text.

- Herodotus, Histories 2.141. Return to text.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 10.1.4–5. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.