How did dinosaurs grow so big?

And how did Noah fit them on the Ark?

Dinosaurs fascinate kids of all ages, not least because of their immense size. Actually, only a few of them were very large, and they are understandably the most famous. But most were a lot smaller—Compsognathus was only as big as a chicken. Dr Neil Clark, curator of paleontology at the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow, has recently discovered in the Isle of Skye a footprint of a sparrow-sized dinosaur looking like Coelophysis.1

What about the huge ones? Were they simply old?

There were comparatively few real kinds of dinosaur compared to the number of named ‘species’.

Until fairly recently, scientists thought that the dinosaurs could grow so big because they were reptiles. Reptiles can keep growing till they die, while mammals (including man) stop growing at adulthood. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica CD (2005):

‘The significant difference between growth in reptiles and that in mammals is that a reptile has the potential of growing throughout its life, whereas a mammal reaches a terminal size and grows no more, even though it may subsequently live many years in ideal conditions’ [italics added].

The pro-evolution Walking with Dinosaurs website provided an example of this reasoning:

‘A huge animal called Seismosaurus was found in New Mexico and many palaeontologists believe it is really an old Diplodocus. It weighed 30 tonnes and was 45 metres (150 ft) long.’2

And the Walking with Dinosaurs TV series itself claimed that the huge size (150 tonnes) they claimed for the pliosaur Liopleurodon meant it must have been over 100 years old.

Teenage growth spurts

But this couldn’t explain everything. There’s no way a gecko or skink, for example, will grow as big as a 50-tonne Brachiosaurus. Gregory Erickson, a paleontologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee, and other researchers, studied dinosaur bones for their equivalent of growth rings.3 They showed that dinosaurs had a type of adolescent growth spurt—the pattern is called sigmoidal, or s–shaped. In fact, the growth pattern is more similar to that of birds and mammals than that of reptiles.4,5

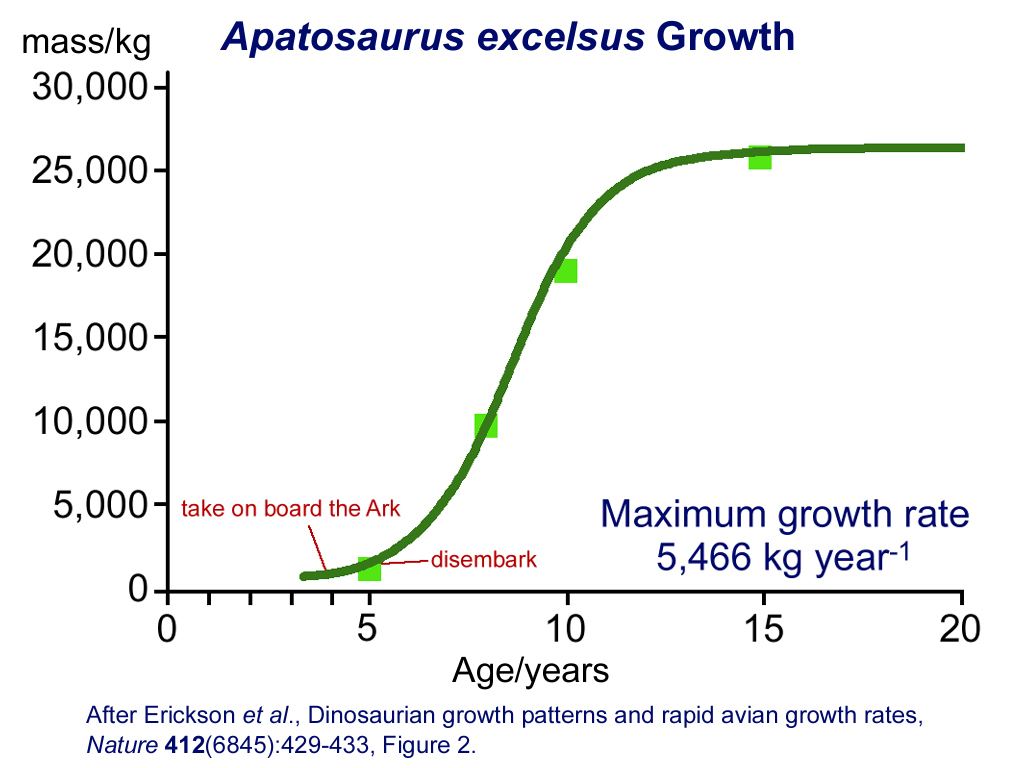

For example, in the huge Apatosaurus, the spurt started at the age of about five years, when the dinosaur was only one tonne. During the spurt, it grew at over five tonnes per year, then the growth levelled off at the age of 12–13, when it was about 25 tonnes (see graph, above right). This was the most dramatic example, but other dinosaurs such as the 1700 kg (3700 lb) Maiasaura and the much smaller 20 kg (44 lb) Syntarsus and Psittacosaurus had the same sigmoid pattern.

Erickson later led a distinguished team in a study just of the tyrannosaurid kind, including the mighty T. rex. This showed the same pattern. At the age of 10, it was still less than half a tonne. But after it started its growth spurt, from age 14–18 it grew at a rate of about 2 kg (4–5 pounds) per day, or a maximum of 767 kg per year. By its early 20s, it was about as big as it would ever be, they said—about 5½ tonnes.6 However, the biggest specimen, the famous ‘Sue’, was also the oldest, but they still estimated that it was only 28 when it died (full of injuries7). Erickson said, ‘T. rex lived fast and died young. They were like the James Dean of dinosaurs.’8

Dinosaur skulls

Top: Apatosaurus excelsus

Bottom: Diplodocus carnegii

The skulls above are from two huge sauropods with different names. Yet the skulls are almost identical. Thus they are likely from the same Diplodocid kind. Diplodocus was a very long and slender variety (27 m long, but only 10 tonnes), while Apatosaurus was a slightly shorter but much heavier variety (25 m, 35 tonnes). So, while there are many dinosaur names, there were most likely comparatively few created kinds. This means that Noah’s Ark needed comparatively few pairs of dinosaurs.

Photos: Don Batten

This study also analyzed other tyrannosaurids called Daspletosaurus, Gorgosaurus and Albertosaurus. These all had the same growth patterns, but not nearly as extreme. So it seems that they were the same created kind, and T. rex was simply a giant form, just as we have in some humans. And as with many giant humans, the giantism comes at a cost.

Superficially, the T. rex body plan might give the impression it was a fast runner. But this structure simply will not allow fast running for this type of animal over one tonne, which the T. rex reached at age 13.6 So the Jurassic Park scene of a T. rex outrunning a jeep is pure fiction—to do that, it would have needed muscle weighing over twice the entire animal!9,10

Noah’s Ark cargo—not a problem!

Bibliosceptics frequently mock the account of Noah and the Ark by asking, ‘How could Noah round up all the huge dinosaurs?’ Of course, this is a leading question—Noah didn’t have to round up anything, because God sent the animals to him (Genesis 6:20).

Certainly, dinosaurs would have been on the Ark: God told Noah to take two of every kind of land animal (seven of the few ‘clean’ animals). Dinosaurs were land animals, and they must have been alive then, because so many of them were fossilized in the Flood.

But these new studies show, once again, that it’s rash to claim that the Bible is wrong based on current data. The sceptic can never be sure that no new data won’t refute the claim of biblical error. These studies suggest a means of fitting the animals on board. God could well have chosen specimens He knew would undergo their growth spurt as soon as they left the Ark. This would solve the common sceptical problem of fitting and feeding huge dinosaurs on the Ark. That is, they weren’t actually that huge while they were on board. The growth spurt just after the Ark would also mean that they could quickly outgrow predators.

And the tyrannosaurid study suggests that a T. rex pair was not required. Rather, another pair, not affected by gigantism, could have represented this created kind. This applies to all the dinosaurs. Diplodocus and Apatosaurus have virtually identical skulls (see photos, above right), so it’s possible that the former was a very long and slender variant and the latter, a shorter, but much more massive, variety. And this diplodocid kind included the huge Seismosaurus, as mentioned above.

In all, although there are an estimated 668 dinosaur ‘species’, it’s more likely that there were only about 55 created kinds with lots of varieties within these kinds.11,12

Update: Female dinosaurs have been discovered to have medullary tissue in their bones—this lines bone marrow and keeps them from losing calcium from their bones when they use it to make egg shells. Furthermore, this tissue has been found in dinosaurs that were not fully grown. It follows that dinosaurs didn’t need to be fully grown before they could reproduce.13

Summary

Noah would have been able to take all the dinosaur kinds on board the Ark because:

- Most dinosaur kinds were small.

- Even the big dinosaurs were small before their teenage growth spurt.

- There were comparatively few real kinds of dinosaur compared to the number of named ‘species’.

References and notes

- The world’s smallest dinosaur footprint? University of Glasgow Newsletter 257, gla.ac.uk, 25 August 2004. Return to text.

- Walking with Dinosaurs Dino fact file: Diplodocus, abc.net.au, 25 August 2004. Return to text.

- For example, there are lines of arrested growth (LAGs) when bones stopped or slowed growing. Also, fast-growing bone has a characteristic fibrolamellar texture, where fibres are quickly deposited, and leave holes that are filled with bony structures called osteons. Conversely, slow-growing bone has a lamellar-zonal structure, which is finely layered. See Stokstad, E., Dinosaurs under the knife, Science 306(5698):962–965, 5 November 2004. Return to text.

- Erickson, G. et al., Dinosaurian growth patterns and rapid avian growth rates, Nature 412(6845):429–433, 26 July 2001. Return to text.

- Fast-growing dinosaurs, Creation 24(1):9, 2001. Return to text.

- Erickson, G.M. et al., Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs, Nature 430(7001):772–775, 12 August 2004. Return to text.

- Sarfati, J., ‘Sue’, the T. rex: Does it show that dinosaurs evolved into birds? Creation 22(4):18–19, 2000. Return to text.

- Gosline, A., Bone rings hold the secrets to dinosaurs’ enormous size, New Scientist 183(2460):8, 2004. Return to text.

- T. Rex was a lumbering old slow coach, New Scientist 173(2332):6, 2 March 2002. Return to text.

- T. Rex: The bigger they are, the slower they go, Creation 24(3):56, 2002. Return to text.

- Batten, D. (Ed.), Catchpoole, D., Sarfati, J. and Wieland, C., The Creation Answers Book, ch. 13, Creation Book Publishers. Return to text.

- Sarfati, J., Refuting Compromise, chs. 7–8, Master Books, Arkansas, USA, 2004. Return to text.

- Morton, M.C., Teen pregnancy in dinosaurs a good thing, Geotimes, January 2008. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.