Journal of Creation 34(3):35–38, December 2020

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

A fantastical dinosaur journey

A review of: The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: The untold story of a lost world by Steve Brusatte

Macmillan, London, 2018

Steve Brusatte (b. 1984) is a rising star in the world of palaeontology and dinosaurs (figure 1). He was born in the USA, but is now Reader (the second highest rank of lecturer) in Vertebrate Palaeontology at the University of Edinburgh. He has discovered many new species of fossil vertebrate. Thus, he is often looked to for some relevant quote when a new discovery in his field of expertise is found.

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs is his eighth book and is rather adequately described as an adult pop science book, which makes it easy to digest. There are no references within the main text for the reader, but at the end of the book there are notes on the sources Brusatte used for each chapter.

It follows a narrative style telling the reader the ‘current’ evolutionary story that Brusatte holds to, hence he must add some important disclaimers. Interwoven throughout dinosaur history are personal stories involving Brusatte, alongside a who’s who of other up-and-coming palaeontologists, as well as those firmly established as leaders in their field. These insertions read more like someone vying for credibility rather than adding anything of any genuine substance to the text. He also includes the background to a number of historical dinosaur bone hunters who are interesting in their own right.

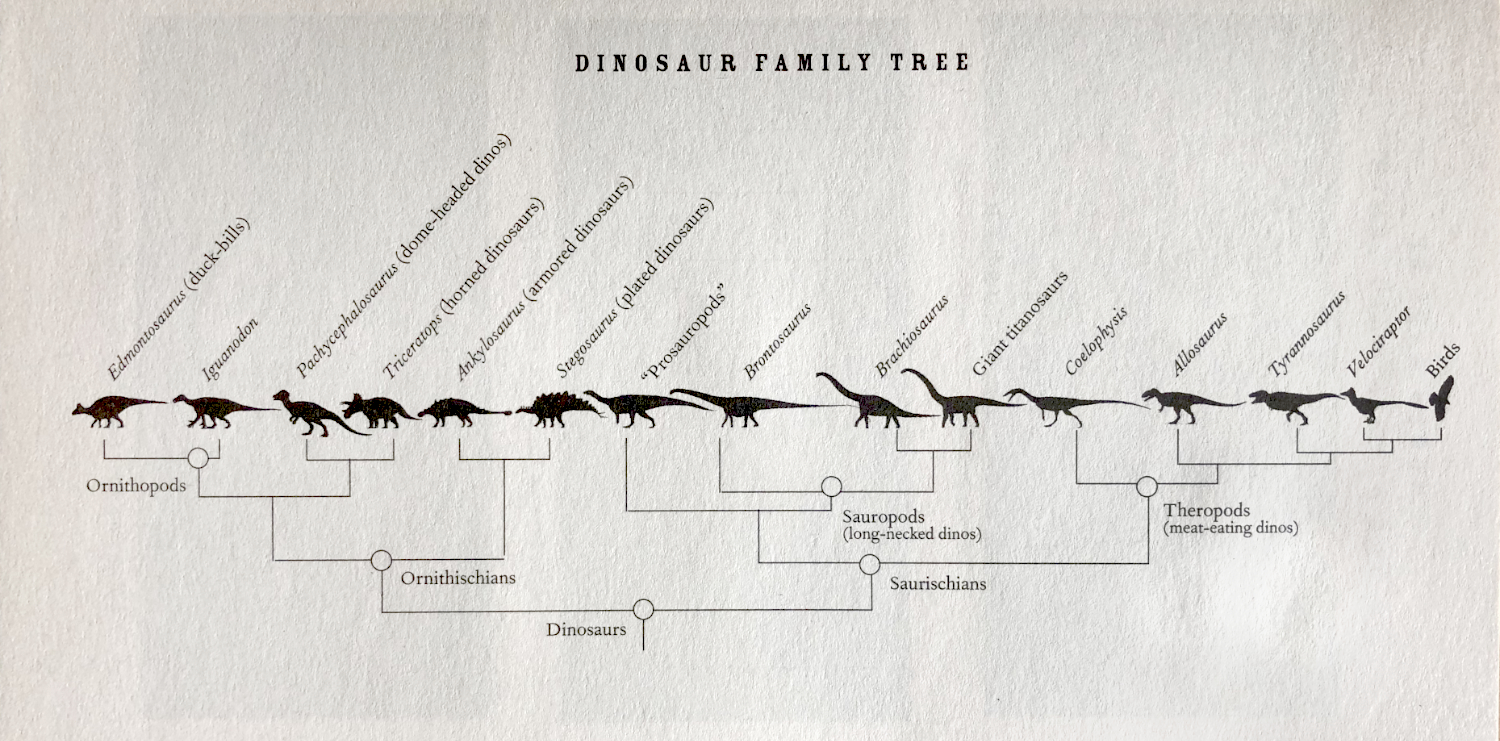

The premise of the book is stated in the title, and, other than the (many) insertions mentioned above, the text attempts to tell the story of the dinosaurs in three phases. Their beginning, their dominance, and their extinction. All three phases are surrounded by mass extinction events. Before the book starts properly there is a dinosaur family tree included which looks more like a creationist dinosaur kind line-up (with the exception of birds) rather than an evolutionary one (figure 2). It also sums up the evolutionary depth of the book. As the family tree shows, there is no adequate precursor to the dinosaurs, and there were distinct kinds.

There are currently around 1,000 dinosaur species, which biblical creationists place in 50–55 kinds. Due to the large number of animal species, skeptics have asked how they could all have fitted on Noah’s Ark. The high numbers that this would require for dinosaurs alone is fodder for such skeptics. Brusatte explains that “A new species of dinosaur is currently being found, on average, once a week. Let that sink in: a new dinosaur every … single … week. That’s about fifty new species each year” (p. 6). Apart from the maths, it alludes to more going on. There appears to be a systematic failure in current palaeontology whereby even the smallest difference between dinosaurs which are obviously related1 results in their being given different names, rather than being grouped together using their abundant similarities.

The dawn of the dinosaurs

Brusatte is a very clear evolutionist, believing that “Rocks record history; they tell stories of deep ancient past long before humans walked on earth” (p. 13). The story starts with a vividly described picture of the alleged Permian–Triassic (P–Tr) extinction, 252 Ma ago. Volcanoes, streams of liquid rock, explosions, eruptions, dust, ash, acid rain, a landscape scorched with lava, barren landscapes, food chains collapsing. It is claimed to be the most severe mass extinction of all, in which around 90% of all species disappeared. However, as life is resilient, it was in this gap that the scene was set for dinosaurs to make their appearance—enter the Triassic.

This is when the story gets very messy, with Brusatte trying to explain to the reader exactly how dinosaurs took advantage of the extinction, and where they came from. He never does quite get around to this and ties himself and the reader in knots when attempting to do so. The first animal we are introduced to is the 250-Ma–old Prorotodactylus which was identified from a trackway in Poland.

However, Prorotodactylus is an ichnogenus, which is a classification based solely on fossil traces such as tracks or burrows where these are deemed to be distinctive and not from a type known from other evidence. In other words, no actual physical fossils of the animal have been found. It is a problem for evolutionists that trackways are often found millions of evolutionary years before any animal that could have made them. A better explanation is that the animals left tracks while trying to escape from rising floodwaters, but then the Flood caught up and buried the creature on higher land.

Brusatte says that Prorotodactylus was a small, house-cat–sized, quadrupedal archosaur, belonging to the animal line from which dinosaurs allegedly came. It walked in an upright fashion with arms and legs directly underneath the body, as opposed to sprawled out beneath the body.

Until this time, the sprawlers had dominated the Permian, so he calls this transition to walking upright “a landmark evolutionary event” (p. 28). There is no explanation as to how this actually happened. “We may never know exactly why … [they] started walking upright, but it probably was a consequence of the end-Permian extinction.”

But wait, Prorotodactylus is not just an archosaur, it is actually a dinosauromorph, “a member of that group that includes dinosaurs and the handful of their very closest cousins” (p. 31). Thus, this archosaur-cum-dinosauromorph is actually a dinosaur? Sorry, where exactly did dinosaurs come from again? Allegedly, “At some point, one of these primitive dinosauromorphs evolved into true dinosaurs. It was a radical change in name only. The boundary between nondinosaurs and dinosaurs is fuzzy, even artificial” (p. 33).

From here we learn that from the study of more dinosauromorph trackways in Poland (and others found in France, Germany, and the USA) by 246 Ma ago they are now the size of wolves and racing around on only two legs. This is stated as a fact with no attempt to explain how any such transition took place. The ‘true’ dinosaurs then arose between 240 and 230 Ma ago. But Brusatte doesn’t really know, as maybe some of the footprints made earlier than this

“ … were made by real, true, honest-to-goodness dinosaurs. We just don’t have a good way of telling apart the tracks of the earliest dinosaurs and their closest nondinosaur relatives, because their foot skeletons are so similar. But maybe it doesn’t matter too much, as the origin of the true dinosaurs was much less important than the origin of the dinosauromorphs” (p. 34–35).

For Brusatte, trying to figure out this line between true dinosaurs and their dinosauromorph ancestors continues to cause him ‘headaches’, but they are “ripe to be solved by the next generation of palaeontologists” (p. 34). Kicking the origin of the dinosaurs and their ancestors onto the next generation is not only exceptionally weak, but the reader is left to wonder for a man only in his mid-30’s what he will be doing for the next 20–30+ years himself.

Brusatte has already had to spend some of this time correcting his own thinking about dinosaurs during this period in evolutionary history. At the time of publication, Brusatte believed that there were no truly gigantic sauropods that weighed over ten tons, as they didn’t reach this scale until at least 170 Ma (p. 102). However, the discovery in Argentina of a bus-sized sauropod, ‘dated’ as having lived around 210 Ma, has moved the ‘evolution’ of gigantism back tens of millions of years.2 Ingentia prima is estimated to have been up to 10 metres (32 feet) long and weighed up to 11 tonnes. In response to the discovery Brusatte said, “I think it’s one of the most important dinosaur finds of the last few years. These new fossils force us to rethink when, and how, dinosaurs got so enormous”.3 Not only does this find change evolutionists’ ideas on dinosaur evolution, it also presents them with some gigantic problems. As Brusatte believes that the first true dinosaurs, which were small (cat to wolf size), only entered the scene at the most 252 Ma ago, he now has a significantly shorter period of time to explain how these vast anatomical differences arose.

Dinosaurs rise up

During the Triassic period, the dinosaurs quickly evolved into three major groups: theropods, long-necked sauropods, and ornithischians. Again, no mention of how these radically different body plans actually took shape. But by 200 Ma they were still relatively small in numbers compared to other species that lived at the time (p. 81). In order to mount their global revolution, there needed to be another mass extinction, called the Permian–Jurassic (Tr–J) event.

Around 201 Ma, the supercontinent Pangea breaks up. This sparks a 600,000-year reign of terror with megamonsoons—extreme seasonal changes in wetness and dryness—plus volcanoes spewing out lava. “In all, some three million square miles of central Pangea were drowned in lava” (p. 87), treacherous weather and extreme climates. In this mass extinction event over 30% of all species, and maybe more, died out. It was this event, killing off the competition, which Brusatte claims allowed the dinosaurs to greatly diversify in response and rise to their dominant position.

“Somehow dinosaurs were the victors. They endured the Pangean split, the volcanism, and the wild climate swings and fires that vanquished their rivals. I wish I had a good answer for why. It’s a mystery that quite literally has kept me up at night” (p. 98).

But of course, rather than attempt to actually figure this out within his own evolutionary worldview, he again kicks the problem down to the next generation, stating, “Whatever the answer, it’s a riddle waiting for the next generation of paleontologists to figure out” (p. 99). There is unfortunately a very distinct pattern forming in the book in which Brusatte again tells a wonderful story but totally fails to explain any of the details. Having now firmly entered the Jurassic period, this marks the proper period of the dinosaurs’ dominance on the earth’s landscape.

Dinosaurs die out / take flight?

The third piece of the puzzle, where the dinosaurs went after their dominant period in evolutionary history, is also explained by another familiar-sounding mass extinction event. We are again met by fantastical scenes of total catastrophe on a day some 66 Ma ago told form the dinosaur’s perspective. Duckbills eating flowers, raptors chasing prey, T. rexes terrorizing the other dinosaurs. Some of them may have noticed a glowing orb in the sky (p. 309). That orb was a comet or an asteroid, “we aren’t sure which” (p. 315), which collided with the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. It, “hit with the force of over 100 trillion tons of TNT, somewhere in the vicinity of a billion nuclear bombs’ worth of energy” (p. 315). This event led to the extinction of some 70% of species, including all of what he calls “non-avian dinosaurs”, over the course of a few thousand years.

Brusatte then attempts to answer the all-important puzzle of:

“Why did all the non-bird dinosaurs die at the end of the Cretaceous? After all, the asteroid didn’t kill everything. Plenty of animals made it through … . So what was it about T. rex, Triceratops, the sauropods, and their kin that made them a target?” (p. 336).

And we can add marine reptiles—the plesiosaurs and mosasaurs (the ichthyosaurs disappeared earlier, for some unknown reason).

The subsequent answer amounts to that other animals, such as mammals, being smaller and having more omnivorous diets, were able to hide in burrows and eat a greater variety of food. Or crocodiles being able to hide in aquatic ecosystems close to land, and birds being able to lay and hatch their eggs in about half the time of the dinosaurs. Dinosaurs apparently had none of these advantages, so died. That is the disappointing sum totality of the evidence provided. But, of course, dinosaurs didn’t really die out; part of their empire remains.

Brusatte toes the current evolutionary mainstream line, stating that “Dinosaurs are still among us today. We’re so used to saying that dinosaurs are extinct, but in reality, over ten thousand species of dinosaurs remain” (p. 271).

“There is a dinosaur outside my window. I’m watching it as I write this … . A real, honest-to-goodness, living, breathing, moving dinosaur … . The dinosaur I’m watching is a seagull … . Seagulls, and all other birds, evolved from dinosaurs. That makes them dinosaurs” (p. 269–271).

Brusatte accepts Archaeopteryx as the first true bird, ‘dated’ to be 150 Ma old, which comes arrayed in feathers. In an interesting admission Brusatte states that “If dinosaurs did have feathers, that would be the final jab in the gut to the few old-blood leftovers who didn’t accept the connection between dinosaurs and birds” (p. 279). Is this perhaps why feathered dinosaurs are so often falsely pushed and depicted?4,5 While, of course, nothing in the creation model excludes dinosaurs from having feathers, the fossil evidence for this as of yet has been lacking.6

Brusatte presents to the reader Sinosauropteryx as evidence of the start of the journey showing that true non-avian dinosaurs had feathers. Surrounded by a ‘dino fuzz’ it was thought to display proto-feathers. However not only have these instead been shown to be partially decayed collagen fibres in skin,7 but, as Sinosauropteryx comes 20 Ma after Archaeopteryx, any discussion about these alleged protofeathers, which Brusatte calls the “earliest feathers” (p. 292), is a moot point. The reality is, as Brusatte points out, “You need fossils to study major transitions, because they’re not the sort of thing we can re-create in the lab or witness in nature” (p. 281). While Brusatte admits that “The first flapping fliers must have originated sometime before 150 million years ago” (p. 303), there are no fossils to study this alleged major transition, which he states would have been 170–180 Ma ago. Neither is there any ancestor to the fully formed bird Archaeopteryx actually proposed in the book.

Dinosaur depictions

When biblical creationists give presentations on dinosaurs, they normally show depictions of them through the past 4,000 years. For example, the late Eastern Zhou (3rd century bc) wine vessel excavated in 1975 from a tomb in Sanmenxia, Henan Province, China, demonstrates this beautifully (figure 3). There are four sauropod dinosaurs, one on each side, which may very well be depicting a Camarasaurus. When discussing some dinosaur footprints that Brusatte found on the Isle of Skye, Scotland, he writes:

“If I were handed a blank sheet of paper and a pen and told to create a mythical beast, my imagination could never match what evolution created in sauropods. But they were real: they were born, they grew, they moved … . And there’s absolutely nothing like sauropods around today—no animals with a similar long-necked and swollen gut type body, no creatures on land that even remotely approach them in size” (p. 108).

Brusatte goes on to inform the reader that when sauropod dinosaurs were originally found, in the first half of the 1800’s, the finders were in a bind as they didn’t know what they were, thinking, due to their size, they were whale bones. If it is the case that his own imagination could not stretch to create such beasts, and that it took a number of years to figure out what the sauropod bones belonged to, then why do we have depictions of dinosaurs from every continent except Antarctica going back a few thousand years? Rather than such clear and true images coming from someone’s wild imagination, it makes much more sense that they are actual depictions of animals that people saw and interacted with. Such evidence is not considered in this book.

Same old, same old

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs presents little new in the way of major up-to-date discoveries and fails to interact at all with the discovery of dinosaur soft tissue, which has been an established fact for over 15 years. While introducing mass extinction events for the dinosaurs’ rise, dominance, and fall, there is little to no substance for how any of these alleged events actually contributed to their history other than dumb luck that they survived the first two and were snuffed out in the third. There is no explanation at any point as to how the range of dinosaur body plans came about or changed from small animals (cat- to wolf-sized) to the huge and memorable Tyrannosaurus rex or Diplodocus. The numerous insertions about Brusatte’s own interactions with other palaeontologists feel like they are there to pad out a made-up story that lacks any real detail.

From a biblical perspective, the mass extinction (death) events aforementioned should not be viewed as separate events as all took place during the Flood in a considerably shorter time frame. The mass fossil graveyards are testimonies to judgment by God as outlined in Genesis 6–8. And, of course, the Bible is clear that their kinds were preserved in Noah’s Ark and lived on after the Flood. That some of the animals such as dinosaurs8 are not found in more modern rock layers does not mean that they did not live beyond this point. As Brusatte acknowledges, “Absence of evidence is not always evidence of absence, as all good paleontologists must constantly remind themselves” (p. 59).

While Brusatte is a good storyteller, he may fare better with creating a fantastical Hollywood film than describing the historical past. In the end, his so-called untold story just feels like the same old told (discredited) story.

References and notes

- See, for example: Catchpoole, D., Dino ‘puberty blues’ for palaeontologists, creation.com/dino-puberty-blues, 15 Jun 2010. Return to text.

- Apaldetti, C. et al., An early trend towards gigantism in Triassic sauropodomorph dinosaurs, Nature Ecology & Evolution 2:1227–1232, 2018 | doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0599-y. Return to text.

- Geggel, L., Discovery of ‘first giant’ dinosaur is a huge evolutionary finding, livescience.com, 10 July 2018. Return to text.

- Robinson, P., Sorry, how many feathers did you find? creation.com/sorry-how-many-feathers-did-you-find, 1 December 2016. Return to text.

- Robinson, P., Separating fact from fiction in a farcical story! creation.com/dino-feathers-southpole, 3 December 2019. Return to text.

- Thomas, B. and Sarfati, J., Researchers remain divided over ‘feathered dinosaurs’, J. Creation 32(1):121–127, 2018; creation.com/feathered-dinosaur-debate. Return to text.

- Tay, J., Feathered pterosaurs: ruffling the feathers of dinosaur evolution, J. Creation 33(2):93–98, 2019; creation.com/feathered-pterosaurs. Return to text.

- Or, for example, the Wollemi pine not found in rock layers below an alleged 65 million years ago, but currently growing in Australia. For more see: Sensational Australian tree … like ‘finding a live dinosaur’, Creation 17(2):13, 1995; creation.com/woll. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.