Journal of Creation 26(2):11–12, August 2012

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Elasmosaurus? No, you goose …

Figure 1. Left, general view of sarcophagus: British Museum EA 32—Princess Ankhnesneferibre from Thebes, dated to the 26th Dynasty. Right, close up of the hieroglyph in question. Click for larger images.

There are several excellent examples of ancient art and/or artefacts that unmistakably depict dinosaurs. In the evolutionary timeline, such creatures are supposed to have died out tens of millions of years before any human walked on Earth.1

Since such artwork dates back from a period well before there were any books illustrating dinosaurs from reconstructed fossils, it strongly suggests human encounter with living examples of these reptiles.

Past co-existence of dinosaurs with humans is a straightforward deduction from biblical creation. Thus, when such examples are convincing, they serve as a useful reinforcement of (and evidence for) the truth of Genesis history.

Unfortunately, there is also a tendency for some overenthusiastic creationists to ‘see’ dinosaur images almost everywhere in ancient works, well beyond what the evidence warrants.

One driver in this is the human tendency to see hoped-for patterns in randomness—e.g. the ‘face of Jesus’ or other ‘deities’ in clouds at sunset, or in the random dots on a cork flooring tile; even the image of the Virgin Mary on a piece of cheese toast—sold on Ebay for thousands of dollars.2

At other times, a drawing or figurine may give tantalizing hints of a dinosaurian creature, such that the verdict has to be that it is at least ‘possible’… but given the philosophical and spiritual importance of the whole creation/evolution debate, that should never be sufficient. It would seem far better to err a thousand times on the side of caution than to bring any aspect of biblical apologetics into disrepute. The good examples referred to are already powerful enough to silence any fair-minded critic.

But it is particularly inexcusable when someone makes a claim about an object without even basic checks on the item in question. An example of this was recently doing the rounds of the internet, based on a YouTube video that referred to an item in the British museum.3 It is a series of Egyptian hieroglyphic symbols with one that looks like an Elasmosaurus (figure 1).

On receiving this, we asked creationist Egyptology expert Patrick Clarke to comment. He wrote:

“The sign is known to Egyptologists by the Gardiner designation G54;4 it is pronounced snḏw. It is a trussed goose. The word goose is, in any case, written as srw, so there should be no confusion about context. There are only two contextual usages known:

- as a determinative for goose (surprise, surprise)

- where fear is involved.

“In this inscription, it is the fear context which applies, due to the sarcophagus and its association with death and its unknowns. Snḏw can act as a noun (fear), or as a verb (to be afraid of). Regarding this sarcophagus, which I know well, snḏw acts as a noun—thus the vertical text portion shown in the video reads, ‘he fears that which is in the Amy [duat—i.e. the underworld].’

“This is a normal funerary text for the period concerned. The use of this symbol for ‘fear’ makes intuitive good sense. The goose has reached a destiny to be feared; even in English we use the expression that someone’s ‘goose is cooked’ to mean that an unwelcome end, i.e. one to be feared, has come to them.”

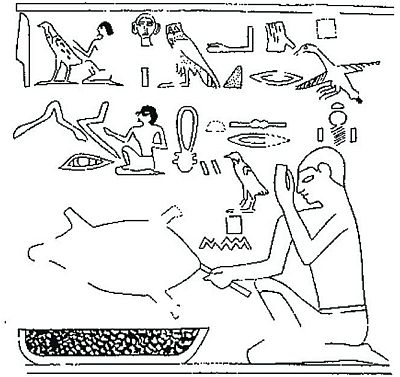

Clarke also supplied a line drawing of an inscription on a stele from Meir Tomb III (figure 2).5

Commenting on this drawing, Clarke wrote:

“Translated the scene reads: ‘I have been roasting since the beginning of time—I have never seen the like of this goose.’

“The three vertically placed hieroglyphs (read top to bottom) in front of the man’s head and raised hand are the one form of the Egyptian for ‘goose’, i.e.srw (see the three top to bottom). The other is

6.”

Note the similarity of the goose being roasted to the hieroglyph in question, including the alleged ‘flippers’; the head and neck are missing for obvious culinary reasons. And when the hieroglyph is viewed close up, the head looks more like that of a waterbird than anything else.

References

- See creation.com/bishop-bells-brass-behemoths. Return to text.

- www.msnbc.msn.com/d/6511148/ns/us_news-weird_news/t/virgin-mary-grilled-cheesesells/, accessed 13 April 2012. Return to text.

- YouTube clip, “Dinosaurs in ancient Egypt? (It’s NOT a scorpion!!)”, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8AtYXjOIeZ0&feature=context&context=C470f6e0ADvjVQa1PpcFNb4asLv7chvmIqwB3yvStaujFzJ1DIsWQ. Return to text.

- Vygus, M., Vygus Dictionary, www.pyramidtextsonline.com/documents/VygusDictionaryApril2012.pdf, p. 680, 2012; accessed 2 April 2012. Return to text.

- Featured in: Blackman, A.M., The Rock Tombs of Meir, vols. I and II, Egypt Exploration Society, London, 1914 and 1915. It was drawn by Richard Parkinson, Department of Egyptian Antiquities, British Museum and features in Collier, M. and Manley, B., How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs, British Museum Press, London, p. 1, 1998. Return to text.

- As illustrated in Collier and Manley, ref. 5 p. 6. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.