Journal of Creation 35(3):116–124, December 2021

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Developments in paleoanthropology

This paper discusses some of the more recent fossil finds and/or developments in paleoanthropology from a creationist perspective. This includes a newly described Homo erectus cranium from South Africa, updates on Homo naledi, the controversy over a femur associated with Sahelanthropus tchadensis, and troubles for Australopithecus sediba. Also discussed is the European ‘bipedal’ ape Danuvius guggenmosi, as well as the implications such apes have on the supposed ‘hominin’ status of the australopithecines. The recently described Harbin cranium and Nesher Ramla Homo are also discussed.

Homo erectus in South Africa

In 2020 there was published the description of a Homo erectus cranium (DAN5/P1) from Gona, Afar, Ethiopia, with the exceedingly small cranial capacity of 598 cc (cubic centimetres), the smallest of any adult Homo erectus cranial capacity known in Africa.1 I subsequently discussed this specimen, along with the partial Homo erectus cranium BSN12/P1 (also from Gona) that was also described in the above paper.2 Another small Homo erectus cranium (DNH 134) was published soon after the DAN5/P1 cranium, but was not incorporated in my paper. DNH 134 (figure 1), along with an Australopithecus (Paranthropus) robustus cranium (DNH 152), were discovered in the Drimolen Main Quarry in South Africa and dated at between an alleged 1.95 to 2.04 Ma (million years ago).3 As for the setting the fossils were found in, Herries et al. reported that both “DNH 134 and DNH 152 were recovered partly from decalcified and partly from lightly calcified breccia and in close contact to solid breccia.”4 The DNH 134 cranium was recovered as a series of individual pieces during excavations in 2008, 2015, 2016, and 2019, with the single piece from 2008 said to be “not recognized as hominin until more of the cranium was recovered in 2015”.5

According to Herries et al.: “DNH 134 represents the oldest fossil with affinities to H. erectus in the world.”6 The cranial capacity was estimated at 538 cc, and assuming an age at death between 2 and 3 years, the authors estimated that the DNH 134 individual could have reached an adult cranial capacity between 588 and 661 cc according to a human model.7 Paleoanthropologist Susan Antón commented on the DNH 134 cranium assignment to Homo erectus as follows:

“The size and shape of the DNH 134 braincase (vault) merit its assignment to Homo and preclude its affiliation with two species of Homo living on the continent at the time (H. rudolfensis and H. habilis). H. erectus has a distinctly shaped vault compared with other early Homo species and one that is present even in young individuals; on this basis, the authors recognized DNH 134 as H. aff. erectus.”8

The distinct cranial vault shape of Homo erectus mentioned by Antón is likely what Stephanie Baker, a researcher involved in the study, described as “the characteristic teardrop shape seen in all Homo erectus specimens”—when viewed from above.9 Baker also stated that the DNH 134 Homo erectus specimen is “the first recorded representative of the species in South Africa.”9 However, convincing arguments have been advanced that the adult SK 847 cranium from Swartkrans, South Africa, is Homo erectus,10 which would mean that DNH 134 is not the first recorded representative of Homo erectus in South Africa. For example, on the status of SK 847, paleoanthropologist Ronald Clarke stated in 1985 that:

“Although one cannot say whether 847 had a brain size like that of Homo habilis or early Homo erectus, the erectus-like morphology of the frontal bone (which is not seen in any of the Homo habilis crania) plus the remarkable overall similarity to 3733 convinces me that 847 must now be classified as an early Homo erectus.”11

On the brain size of SK 847, due to the incompleteness of the specimen, which has most of its neurocranium missing, any estimate of its cranial capacity would be inaccurate, although it is likely to be very small.12

Of interest is the statement by Herries et al. that “DNH 134 is strikingly similar to the Mojokerto H. erectus cranium in overall cranial shape”, with the DNH 134 cranium superimposed on the Mojokerto cranium to illustrate the point.13 The cranium of the Mojokerto child from Mojokerto, Java, Indonesia was discovered in 1936, and has been dated to an alleged ~1.81 Ma—but later redated to <1.49 Ma.14 Its developmental age is uncertain, with proposed ages at death ranging between 0 and 8 years.14 According to Antón, “Reasonable cranial capacity estimates of the Mojokerto specimen range between 636 and 700 cc … with a direct liquid replacement measurement of 673 cc”.15 Antón subsequently stated that:

“If Mojokerto’s development is comparable to that of a 4–6-year-old modern human when 80–90% of cranial volume is attained … , an adult cranial capacity of 740–860 cc would result, assuming Hss [Homo sapiens sapiens] neural growth standards.”15

That characteristic features of the Homo erectus morphology are present in juvenile specimens indicates that the key features of Homo erectus morphology arose during the developmental processes to maturity (the adult stage), and not during the aging process.

Also, the striking similarity between the DNH 134 and Mojokerto crania, specimens as far apart as South Africa and Indonesia, reinforces the notion that Homo erectus individuals from different regions of the world (e.g. Indonesia, China, East Africa, North Africa, India, Georgia, Turkey) ultimately trace their origins back to an original and diverse Homo erectus population, likely from Babel.16 Although not recent, there is also controversial evidence suggesting Homo erectus people may even have migrated to Mexico. According to evolutionist Jeff Meldrum:

“Nearly as controversial as sasquatch itself is the interpretation that a fragment of a fossilized human brow ridge found at Mexico’s Lake Chapala may be from the skull of a relic Homo erectus. The attribution is a matter of considerable debate, but the close resemblance of the fragment to the cranial anatomy of Homo erectus is inescapable.”17

According to Associated Press, Mexican professor Federico Solorzano, a teacher of anthropology and paleontology, was sifting through his collection of old bones from the shores of Lake Chapala when he noticed “a mineral-darkened piece of brow ridge bone and a bit of jaw that didn’t match any modern skulls.”18 The article then goes on to state:

“But Solorzano found a perfect fit when he placed the brow against a model of the Old World’s Tautavel Man—member of a species, Homo erectus, that many believe was an ancestor of modern Homo sapiens.”18

If Homo erectus is established as having been in Mexico, then this would require evolutionists to further revise their ‘evolving’ models of human evolution. From the fuzzy photo of the brow ridge, it is difficult to comment on it.18 Hopefully, more fossils from this region are discovered in the future, which can shed more light on the above claim.

Homo naledi updates

The allocation of DNH 134 to Homo erectus raises the question of whether the specimens allocated to Homo naledi should also be subsumed into this category. This is especially so given that the Rising Star cave system, where the Homo naledi fossils were found, is only about 800 metres from Swartkrans,19 where SK 847 was discovered, and 7–8 km from the Drimolen site,20 where DNH 134 was found. From a creationist viewpoint, all specimens genuinely belonging to Homo erectus should ultimately be reclassified as Homo sapiens if Homo erectus individuals were fully human, i.e. descendants of Adam and Eve. The sites are within a few hours walking distance from each other, and its erectus-like specimens all have small brain size. Ignoring the evolutionary-assigned ages of the specimens, it seems reasonable to suggest there is a connection between the specimens.

I have previously suggested that Homo naledi were erectus-like post-Babel humans, and that some of the odd skeletal features observed in the fossils, including the very small cranial capacity, could possibly be explained if some of them suffered from cretinism, a developmental pathology.21,22 The small cranial capacity observed in many Homo erectus specimens was discussed in more detail by me in 2020.2 Some, such as the small cranial capacities in the Dmanisi, Georgia Homo erectus group, may likewise be explained by a pathology, such as cretinism. If you include other ‘robust’ crania, which appear to be omitted from the Homo erectus category mainly because of their large cranial capacity (i.e. an example of circular reasoning), and related features, then it seems that there was a huge natural variation in cranial capacity of ‘robust’ humans. I also gave an example of a modern human with normal intelligence, whose cranial capacity was on the lower end of the Homo erectus range. This person’s cranial capacity would not have been that different in size to the DNH 134 Homo erectus cranium discussed above, if DNH 134 had reached adult cranial capacity. Also, some (but not all) of the difference in brain size between Homo erectus and modern humans may be explained by body size differences; this, on average. appearing to be larger in modern humans.2 However, as yet there is no definitive answer as to why proportionally so many Homo erectus specimens had a small brain size, and hence a small cranial capacity.

More than five years have passed since Homo naledi was first announced to the world, and the fanfare over the fossils has subsided somewhat, as have publications on the finds. A study by Li et al. had as a major goal “to test the hypothesis that Homo naledi did not have a flat foot as it is widely considered by prominent researchers”.23 From the study the authors reported that:

“Obtained results strongly suggest that Homo naledi does not have flat foot[sic]. Their relatively wide forefoot and narrow calcaneus reveal that Homo naledi is skilled in running with forefoot striking the ground, a better pattern for barefoot running because the ankle will be less likely to sprain. Running with forefoot striking can benefit from proprioception as well as the shock absorption function of longitudinal foot arch.”24

This adds to the evidence that Homo naledi individuals were fully human, as does the relative limb size index (RLSI) measurement of the LES 1 (Neo) Homo naledi partial skeleton, the RLSI of LES 1 described as being “decidedly human-like”.25 RLSI is used to quantify limb joint proportions per individual, and according to Prabhat et al. “is the logged ratio of geometric means calculated from upper (forelimb) and lower (hindlimb) limb measurements and quantifies whether a given specimen has relatively larger forelimb or hindlimb joints”.26

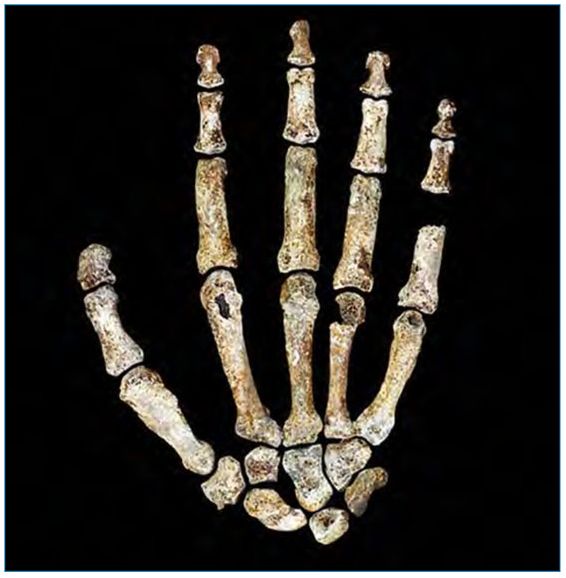

Further support that the specimens assigned to Homo naledi were human comes from a study on the biomechanics and dexterity of the thumb. The study reported that efficient thumb opposition “did not characterize Australopithecus, the earliest proposed stone tool maker”, including “Australopithecus sediba [MH2 specimen], previously found to exhibit human-like thumb proportions.”27 The efficiency was said to be “similar to that of present-day chimpanzees”.28 This indicates that even if some australopithecines may structurally have exhibited human-like thumb proportions, functionally their ability to move the thumb, particularly in terms of opposition (i.e. bring the tip of the thumb in contact with other fingertips of the same hand), was not any better than that of chimpanzees (who have shorter thumbs than humans). In contrast, it was reported that “later Homo species, including the small-brained Homo naledi, show high levels of thumb opposition dexterity”.29 Commenting on the study, Parletta stated that “more recent hominins showed greater levels of thumb dexterity similar to those of modern humans, including Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, as well as Homo naledi.”28 Discussing the high level of thumb dexterity in Homo naledi (figure 2 shows the Homo naledi hand), Karakostis et al. stated that:

“Although no artifacts have been found in association with this taxon as yet, such enhanced manual abilities in this small-brained species suggest a decoupling of the traditionally assumed correlation between brain size and tool-using skills in the fossil record and therefore a potential greater importance of brain complexity in cultural behavior.”30

Australopithecus sediba troubles

From an evolutionary viewpoint, the DNH 134 Homo erectus find (discussed above) essentially eliminates the possibility that Australopithecus sediba, supposedly dated to 1.977 Ma,31 was the ancestor to Homo. On this, Herries et al. commented that:

“It has been postulated that A. sediba is a good candidate for the ancestor of Homo … , although much older fossils attributed to Homo exist … . A. sediba can only be ancestral to Homo in southern Africa if a population existed before DNH 134, for which there is no current evidence … .”6

Regarding Australopithecus sediba, a recent study by Rak et al. of the mandibles belonging to the two partial skeletons (MH1 and MH2) assigned to the species concluded that “the specimens represent two separate genera: Australopithecus and Homo”, with the MH1 individual suggested as belonging to Australopithecus africanus.32 The aspect of the mandibles examined was the upper ramal morphology, mainly the shape of the mandibular notch between the condylar process and coronoid process. According to Rak et al.: “the MH2 mandible falls in the group that exhibits the generalized configuration, a group that includes H. sapiens. The MH1 mandible [see figure 3], on the other hand, is clearly clustered with the australopiths.”33 This latter group (which includes MH1) is said to exhibit a ‘derived’ or ‘specialized’ configuration.34 However, Ardipithecus ramidus, as well as chimpanzees and orangutans, also display the ‘generalized’ configuration of the former group (which includes MH2),35 and so from a creation viewpoint one should not read too much into this finding.

Concerning “the question of the Homo species at play”, in regards to the MH2 individual, the authors stated that “we do not deal with nomenclature on a species level” and so did not answer that question.33 When evolutionists label a specimen Homo or early Homo one has to consider the context, as it can mean human, as in, e.g., Homo erectus, but it can also mean Homo habilis. On Homo habilis, my assessment is that it appears to be a phantom species, i.e. a composite species made up of mostly australopithecine remains, but also a few Homo erectus remains, that have been bundled together and marketed as an ‘apeman’ (hominin) species.36 Rak et al. concluded that “Au. sediba seems to represent a mixture of two hominin taxa, leading Berger et al. to refer to the new species as a transitional one”.33 The authors finished their paper with the following statement:

“All the australopiths on which the relevant ramal morphology is preserved (Au. afarensis; Au. africanus, including the Australopithecus specimen at Malapa; and certainly Au. robustus) are actually too derived to play the role of a H. sapiens ancestor. Given that Malapa already contains representatives of two hominin branches, one of which appears to be Homo, we must seek the latter’s origin in geological layers that are earlier than those at Malapa, which are dated at approximately 2 million years before present … . Support for such a scenario can be found in earlier Ethiopian fossils attributed to the genus Homo: A.L. 666, dated at 2.4 million years … , and LD 3501, dated at 2.8 million years … .”37

From the above statement, it seems that Rak et al. have a different evolutionary scenario in mind, with an origin of Homo that does not include Australopithecus sediba. In my assessment the MH1 and MH2 Australopithecus sediba specimens both belong with the australopithecines,38 an extinct apish primate group, and the study by Rak et al., being heavily based on evolutionary interpretations, does little to change this. However, no doubt there is more to come in this dispute between opposing evolutionary groups.

Bipedal apes and the australopithecines

John Relethford, in discussing general characteristics “shared by all of the early hominins” in his textbook on biological anthropology, stated that “All are classified as hominin because they show evidence, direct or indirect, of being bipedal (although, as noted below, some of this evidence for the earliest possible hominins is being debated).”39As stated by Tracy Kivell:

“The commitment to terrestrial bipedalism, characterized by skeletal adaptations for walking regularly on two feet, is a defining feature that enables the assignment of fossils to the hominin lineage—which comprises all species more closely related to humans than to chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) or bonobos (Pan paniscus), our two closest living relatives.”40

As indicated above, bipedalism is the defining feature that evolutionists use to assign fossils to the ‘hominin’ (or ‘hominid’) lineage. As such, numerous documentaries, books, magazine articles, etc., promote the idea that ape-like creatures in Africa were on their way to becoming human because their fossils indicated they walked upright in some manner. As an example, consider the statement by Brian Handwerk in a recent article for the Smithsonian Magazine:

“The long evolutionary journey that created modern humans began with a single step—or more accurately—with the ability to walk on two legs. One of our earliest-known ancestors, Sahelanthropus, began the slow transition from ape-like movement some six million years ago, but Homo sapiens wouldn’t show up for more than five million years.”41

However, what if apes living supposedly millions of years earlier than this already walked upright—yet remained apes? Bipedalism would then be nothing novel, and animals like the apish australopithecines (members assigned to the genus Australopithecus) were likely, like these other ‘bipedal’ apes, simply an extinct group of apish primates unconnected to any supposed evolutionary lineage.

First there was Oreopithecus bambolii, then later Rudapithecus hungaricus, followed soon after by Danuvius guggenmosi, all fossil apes from Europe with claims of upright posture and/or being bipedal.42 Dated to allegedly 11.62 Ma, Danuvius guggenmosi, according to its discoverer Madelaine Böhme, had unusual features for an ape, i.e. the “ability to stand straight with its knees and hips fully extended and a lower back that curved gently to lend it stability.”43 Böhme points out that when “today’s great apes stand on two feet, they keep their knees and hips bent”, and their “lower backs are inflexible and too short for them to be able to stand upright with extended hips.”44 Paleoanthropologist Jeremy DeSilva, who has examined the Danuvius guggenmosi fossils, stated that:

“Böhme and her team concluded that over 11 million years ago Danuvius was upright and walked not on the ground, but in the trees. If Böhme is right, bipedalism did not emerge from the ground up, but from the trees down. From my own observations of the fossils, I saw no reason to contradict these findings, but they remain controversial and contested.”45

As indicated, the above finding is a real blow to the idea that bipedalism equals hominin (i.e. apeman). That is, if apes/primates in Europe were built for some form of bipedalism and/or upright posture, yet were not hominins, then why would bipedal-like features in the australopithecines from Africa mean they were hominins? Hence, the argument of evolutionists that the australopithecines were hominins because they were in some way bipedal collapses. In fact, however, the argument that the australopithecines were hominins because they were bipedal is invalid reasoning per se, regardless of whether there were ‘bipedal’ apes/primates in Europe or not.

The Bible does not address the issue of locomotion in primates, and so, from a creation viewpoint, if bipedal apelike primates existed, it does not contradict Scripture. If God created humans bipedal, why would He not use variation on a similar design pattern for some other primates? Given how many non-human primates there are, if considering both extant and extinct species, it would in some ways seem a bit unusual if He had not. The australopithecines may have been one such primate group.

According to evolutionist authority Charles Oxnard, “The various australopithecines are, indeed, more different from both African apes and humans in most features than these latter are from each other.”46 He further stated that:

“For instance, though bipedal, it is likely that their bipedality was mechanically different from that of humans. Though terrestrial, it is further likely that these fossils were accomplished arborealists. The combination of the two functions within the same set of creatures is certainly unique among hominoids.”46

According to DeSilva:

“We used to think that throughout human evolution, there was only one way to walk. But we now know that is not the case. Millions of years ago, different yet related species of upright walking Australopithecus, living in different environments, walked in slightly different ways.”47

Putting aside the above evolutionary assumptions, from a creation viewpoint the australopithecines appear to have been unique primates that were at home in the trees, as well as on the ground. If they were capable of an upright posture, it was likely a design feature also useful for life in the trees, e.g. for reaching overhanging fruit with their hands while walking on a limb, as well as for tree climbing. So any ‘bipedal’ locomotion was not necessarily like that of humans. The australopithecines appear to have exhibited considerable variation, as do the great apes, and so the locomotor pattern likely varied between different species in the genus Australopithecus. Likely, the australopithecines were an extinct apish primate group, and, while ape-like, may not necessarily be best regarded as apes, in the sense that monkeys are not classified as apes either.

The Sahelanthropus femur

The Toumaï cranium (figure 4), assigned to the species Sahelanthropus tchadensis and promoted in 2002 as the earliest known hominin, in my assessment appears to have belonged to an extinct ape/ape-like primate, with claims of bipedalism unsubstantiated.48 The possible existence of a Sahelanthropus tchadensis femur received considerable attention in 2018, but it still remained unpublished and shrouded in secrecy.49 In 2020 a study on the femur (referred to as the TM 266 femur) was finally published, and its finding, that “the overall morphology of TM 266 appears to be closer to that of common chimpanzees than to that of habitually bipedal modern humans”,50 poured more doubt on the ‘hominin’ and bipedal status of Sahelanthropus tchadensis. The authors (Macchiarelli et al.) of the study concluded that the “lack of clear evidence that the TM 266 femur is from a hominid that was habitually bipedal further weakens the already weak case … for S. tchadensis being a stem hominin.” 51 Reporting on this in New Scientist, Michael Marshall summed up the finding as follows:

“The leg bone suggests that Sahelanthropus tchadensis, the earliest species generally regarded as an early human, or hominin, didn’t walk on two legs, and therefore may not have been a hominin at all, but rather was more closely related to other apes like chimps.”52

The lead scientist of the group that discovered the remains of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Michel Brunet of the University of Poitiers, France, was asked about the femur in 2019 by DeSilva. Brunet is quoted as saying “Toumaï was biped. Yes? If the femur is from biped, then it is from Toumaï. Yes? If it is not from biped, then not from Toumaï.”53 DeSilva went on to state that “According to Brunet, Sahelanthropus was bipedal, the case is closed, and more study or additional fossils—no matter what they look like—will not change his mind.”45 As indicated above, if Toumaï was not bipedal then from an evolutionary viewpoint it could not have been a hominin, and it would hence lose its ‘prestigious’ status as the earliest (stem) hominin. It would also mean the extraordinary media hype surrounding its announcement as the earliest known hominin was fake news.54

A paper by another group (Guy et al.), disputing the finding of the Macchiarelli et al. study (discussed above), and so more favorable to Brunet’s view (although he is not an author), has been published as a preprint under consideration at a Nature Portfolio Journal.55 According to Marshall, “Guy and his colleagues say the femur does show signs of bipedality”, but “Other palaeoanthropologists agree with the analysis by Bergeret-Medina’s team [i.e. Macchiarelli et al.].”52 It seems the dust has not yet settled on this dispute.

Nesher Ramla Homo

As I was about to submit the article to the journal editor, a ‘new’ type of human, called Nesher Ramla (NR) Homo (figure 5), from Nesher, Ramla, Israel, dated to allegedly 140 to 120 ka (thousand year ago), was announced in the journal Science.56 The NR-1 fossil consisted of an almost complete right parietal bone and four fragments of the left parietal, whereas the NR-2 fossil consisted of an almost complete mandible (including a lower left second molar), with both fossils said to likely represent the same NR individual. 57 From analysis of the fossils, the parietal bone appears to show the closest affinity with some specimens classified as Homo erectus and Middle Pleistocene (MP) Homo (usually specimens thrown into the Homo heidelbergensis category), the mandible appears to show the closest affinity with some specimens classified as Neanderthals and Middle Pleistocene Homo, with the molar being closest to Neanderthals.58 Summarizing the morphology of NR Homo, paleoanthropologist Roberto Sáez wrote:

“The study shows the proximity of its features to the Neandertal morphology (such as the shape of the jaw, including the absence of a chin, and the characteristics of the teeth), but also affinities with hominins of 400 ka (in more archaic features of the skull, some similar to those in Homo erectus).”59

In Science, Marta Lahr writes that the Nesher Ramla fossils “suggest that a different population, with anatomical features more archaic than those of both humans and Neanderthals, lived in this region at broadly the same time.”60 According to the authors of the study (Hershkovitz et al.) the “NR fossils could represent late-surviving examples (140 to 120 ka) of a distinctive Southwest Asian MP Homo group”.61 Adding other MP Levantine fossils to this group, the authors wrote:

“… we suggest addressing this Levantine MP paleodeme as the ‘Nesher Ramla Homo’. Its presence from ~420 to 120 ka ago in a geographically restricted area may have allowed for repeated interbreeding with modern human populations such as the people from Misliya Cave … , a notion also supported by their shared technological tradition … . This scenario is compatible with evidence of an early (200 to 400 ka ago) gene flow between modern humans and Neanderthals … and helps explain the variable expression of the dental and skeletal features of later Levantine fossils from the Skhul and Qafzeh populations.”62

Evolutionist Lahr commented that the discovery at Nesher Ramla raises “questions about the coexistence of different hominin populations in this region and complex population dynamics in the Late Pleistocene.”60 From the above, it seems that the authors of the study already acknowledge the notion that NR Homo individuals may have been interbreeding with modern humans, and so from the biological species concept that would make them the same species. Hybridization between subgroups within the same species can give rise to appearances that are sometimes ‘blended’ in general character, and at other times mosaic. Hence, from a creation viewpoint, if there was a diverse human population at Babel, including people with ‘robust’ features, such as Homo erectus, then interbreeding between the different human population subgroups may well explain the NR Homo individuals.

In a companion paper in the same issue of Science, Zaidner et al. wrote: “The evidence from Nesher Ramla demonstrates that late MP Homo fully mastered advanced Levallois technology that until only recently was linked to either H. sapiens or Neanderthals.”63 This indicates, as far as intelligence is concerned, that NR Homo individuals were not inferior to modern humans. According to Bruce Bower, “Attempts to extract DNA from the Nesher Ramla fossils, which would reveal whether interbreeding took place, have failed.”64

Dragon Man

About the same time as the ‘new’ Nesher Ramla Homo type human from Israel was announced, another ‘new’ human, this time from China, officially named Homo longi, 65 was also revealed to the world. The fossil in question was a well-preserved cranium, called the Harbin cranium (figure 6), nicknamed Dragon Man. It got a lot of publicity in the media, with headlines such as “‘Dragon Man’: Scientists say new human species is our closest ancestor”.66 The opening paragraph of this article said the skull “represents a new species of ancient people more closely related to us than even Neanderthals—and could fundamentally alter our understanding of human evolution, scientists announced Friday.” 66 Catchphrases, such as “could fundamentally alter our understanding of human evolution”, are used so often, nearly with every new find, that they are meaningless. Although it does indicate that the theory of human evolution is built on shifting sands—not a very good foundation.

The Harbin cranium was handed over to paleontologist Ji Qiang at the Hebei GEO University in 2018 by a farmer who said the skull had been dug up by a coworker of his grandfather in 1933.67 The cranium was apparently found buried in the riverbank during bridge construction, and subsequently hid in a well to prevent the Japanese from finding it.68 Regardless of the mysterious circumstances surrounding the discovery and previous whereabouts of the cranium, it is nonetheless a very interesting find. Because of its confused history, the exact geographic location of the find remains uncertain, but the researchers directly dated the cranium by the uranium-series disequilibrium method, which allegedly suggested that the cranium was older than 146 ka.69

The cranium is stated as having been recovered in Harbin city in northeastern China. And it is said to be one of the best preserved MP human fossils, massive in size, with a cranial capacity of 1,420 cc, “combined with a mosaic of primitive and derived characters.”70 The authors of the study stated that the Harbin cranium “is characterized by a combination of large cranial capacity, short face, and small check [sic] bones as in H. sapiens, but also a low vault, strong browridges, large molars, and alveolar prognathism as in most archaic humans.”70 The authors said that the Harbin cranium showed “the greatest resemblances to Middle Pleistocene Chinese fossils, such as Hualongdong, Dali, and Jinniushan”, and that their “analyses also suggest a potential link between the Harbin cranium and the Xiahe mandible, a fossil attributed to the Denisovan lineage.”71 According to Ann Gibbons, the authors have yet to test that idea by attempting to extract ancient DNA or proteins from the cranium.68

Gibbons also stated that other researchers “question how the skull was found to be closely related to the Xiahe jawbone, because there are no overlapping traits to compare as the skull has no jawbone.”68 However, as reported by Laura Geggel, some specialists in human evolution believe it is possible that the Harbin cranium is a Denisovan fossil.72 Alison George quoted more paleoanthropologists of that opinion, and also stated that “Although there is excitement at the possibility that the Harbin skull might be Denisovan, there is less enthusiasm about the decision to officially name it as a new species.”73 According to Maya Wei-Haas, “not all the scientists and outside experts agree that Dragon Man is a separate species—nor do they agree about its relative position on the hominin family tree.”74 Writing for National Geographic, Wei-Haas added:

“Many of the skull’s defining characteristics seem to be matters of scale rather than distinct features, says Buck, of Liverpool John Moores University. Even within a species, she says, some variation is expected. Differences in sex, age of the individual, regional adaptations, age of the fossil, and more can all drive slight individual changes.”74

Others, like paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer (a study co-author), believe the Harbin cranium belongs with another species, as stated by Handwerk:

“He currently favors a view that the Harbin fossil and the Dali skull, a nearly complete 250,000-year-old specimen found in China’s Shaanxi province which also displays an interesting mix of features, might be grouped as a different species dubbed H. daliensis.”75

The Dali cranium has affinities with Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis, indicating that erectus and heidelbergensis are not separate species,76 but are subgroups of the same species. From a creation viewpoint, fossil finds such as the Harbin cranium and Nesher Ramla Homo appear to reinforce this point, i.e. that what we are looking at are variations within a single species. It seems to be reinforcing creationist understanding of a continuum of variation between humans broadly categorized as Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Homo neanderthalensis, Denisovan, and Homo sapiens, with these two new finds further connecting the dots, but not in an evolutionary sense. Interbreeding between the different human population subgroups may well explain the features observed. As already mentioned, hybridization between subgroups within the same species can give rise to appearances that are sometimes ‘blended’ in general character, and at other times mosaic. Even if a combination of features has not been observed before, it does not warrant new species status, particularly based on just one or a few individuals.

Conclusions

The striking similarity between the DNH 134 and Mojokerto crania, specimens as far apart as South Africa and Indonesia, supports the notion that Homo erectus individuals from different regions of the world ultimately trace their origins back to an original and diverse Homo erectus population, likely from Babel. Studies indicating that Homo naledi did not have a flat foot, and that its level of thumb dexterity was like those of modern humans, further support the view that these individuals were fully human. That Homo naledi was human is also supported by the discovery of a Homo erectus cranium (DNH 134) about 7–8 km away (at Drimolen) from the Homo naledi site, the Rising Star cave system, as there is likely a connection between them. The discovery of European apes, like Danuvius guggenmosi, that appear to be capable of an upright posture and some form of bipedalism, linked to their tree-dwelling lifestyle, nullifies the argument that the australopithecines were hominins (i.e. ape-men) simply because some of them may have been capable of some form of bipedalism. After a long delay, publication of the femur associated with Sahelanthropus tchadensis has caused more controversy, as well as raising more doubt that it was bipedal, and hence, from an evolutionary viewpoint, doubt that it was a hominin. The recently described Harbin cranium and Nesher Ramla Homo may reflect interbreeding between the different human population subgroups.

References and notes

- Semaw, S. et al., Co-occurrence of Acheulian and Oldowan artifacts with Homo erectus cranial fossils from Gona, Afar, Ethiopia, Science Advances 6(10):eaaw4694, pp. 1–8, 2020. Return to text.

- Line, P., New Homo erectus crania associated with stone tools, J. Creation 34(2): 55–61. For more on Homo erectus see: Line, P., Homo erectus, chap. 14; in: Bergman, J., Line, P., Tomkins, J., and Biddle, D. (Eds.), Apes as Ancestors: Examining the claims about human evolution, BP Books, Tulsa, OK, pp. 217–277, 2020. See pp. 241–242 for more on body mass and cranial capacity. Return to text.

- Herries, A.I.R. et al., Contemporaneity of Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and early Homo erectus in South Africa, Science 368(6486):eaaw7293, p. 1, 2020. Return to text.

- Herries et al., ref. 3, p. 5. Return to text.

- Herries et al., ref. 3, pp. 6–7. Return to text.

- Herries et al., ref. 3, p. 15. Return to text.

- Herries et al., ref. 3, pp. 3, 16. Return to text.

- Antón, S.C., All who wander are not lost, Science 368(6486):35, 2020. Return to text.

- Baker, S., The Remarkable Skulls of Drimolen, popular-archaeology.com/article/the-remarkable-skulls-of-drimolen, 14 July 2020. Return to text.

- Line, P., Homo habilis, chap. 13; in: Bergman, J., Line, P., Tomkins, J., and Biddle, D. (Eds.), Apes as Ancestors: Examining the claims about human evolution, BP Books, Tulsa, OK, pp. 196–198, 2020. Return to text.

- Clarke, R.J., Australopithecus and Early Homo in Southern Africa; in: Delson, E. (Ed.), Ancestors: The hard evidence, Alan R. Liss, Inc., New York, p. 173, 1985. Return to text.

- Wolpoff, M.H., Paleoanthropology, 2nd edn, McGraw-Hill, Boston, MA, pp. 383–384, 1999. Return to text.

- Herries et al., ref. 3, p. 4. Return to text.

- O’Connell, C.A. and DeSilva, J.M., Mojokerto revisited: evidence for an intermediate pattern of brain growth in Homo erectus, J. Human Evolution 65:156, 2013. Return to text.

- Antón, S.C., Developmental age and taxonomic affinity of the Mojokerto Child, Java, Indonesia, American J. Physical Anthropology 102:508, 1997. Return to text.

- Line, ref. 2, pp. 56–57. Return to text.

- Meldrum, J., Sasquatch: Legend meets science, Tom Doherty Associates, LLC., New York, p. 96, 2006. Return to text.

- Associated Press, Mexico discovery fuels debate about man’s origin, deseret.com/2004/10/3/19853733/mexico-discovery-fuels-debate-about-man-s-origins, 3 October 2004. Return to text.

- Berger, L.R. et al., Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa, eLife 4:e09560, p. 3, 2015. Return to text.

- Herries et al., ref. 3, p. 2. Return to text.

- Line, P., Making sense of Homo naledi, Creation 40(4):36–38, 2018. Return to text.

- Line, P., Den of ape-men or chambers of the sickly? An update on Homo naledi, 25 May 2017. Return to text.

- Li, R. et al., Homo naledi did not have flat foot, Homo 70(2):143, 2019. Return to text.

- Li et al., ref. 23, p. 145. Return to text.

- Prabhat, A.M. et al., Homoplasy in the evolution of modern human-like joint proportions in Australopithecus afarensis, eLife 10:e65897; Figure 2—figure supplement 5, p. 8, 2021. Return to text.

- Prabhat et al., ref. 25, p. 3. Return to text.

- Karakostis, F.A. et al., Biomechanics of the human thumb and the evolution of dexterity, Current Biology 31:1–2, 22 March 2021. Return to text.

- Parletta, N., Thumbs up (and over), cosmosmagazine.com/the-body/thumbs-up-and-over, 29 January 2021. Return to text.

- Karakostis et al., ref. 27, p. 1. Return to text.

- Karakostis et al., ref. 27, p. 6. Return to text.

- Pickering, R. et al., Australopithecus sediba at 1.977 Ma and Implications for the Origins of the Genus Homo, Science 333:1421, 2011. Return to text.

- Rak, Y. et al., One hominin taxon or two at Malapa Cave? Implications for the origins of Homo, South African J. Science 117(5/6), Art. 8747, pp. 7–8, 2021. Return to text.

- Rak et al., ref. 32, p. 8. Return to text.

- Rak et al., ref. 32, pp. 1, 9. Return to text.

- Rak et al., ref. 32, pp. 1, 8–9. Return to text.

- Line, ref. 10, pp. 169–214. Return to text.

- Rak et al., ref. 32, p. 9. Return to text.

- Line, P., Australopithecus sediba, chap. 9; in: Bergman, J., Line, P., Tomkins, J., and Biddle, D. (Eds.), Apes as Ancestors: Examining the Claims about Human Evolution, BP Books, Tulsa, OK, pp. 127–136, 2020. Return to text.

- Relethford, J. H., The Human Species: An introduction to biological anthropology, 7th edn, McGraw-Hill, New York, p. 268, 2008. Return to text.

- Kivell, T.L., Fossil ape hints at how bipedal walking evolved, Nature 575:445, 2019. Return to text.

- Handwerk, B., An evolutionary timeline of Homo sapiens, smithsonianmag.com, 2 February 2021. Return to text.

- More details about these apes can be found in my web article: Line, P., Bipedal apes, australopithecines and human evolution, creation.com/bipedal-apes, 17 April 2020. Return to text.

- Böhme, M., Ancient Bones: Unearthing the astonishing new story of how we became human, Greystone Books, Vancouver, pp. 85, 91, 2020. Return to text.

- Böhme, ref. 43, p. 91. Return to text.

- DeSilva, J., First Steps: How upright walking made us human, HarperCollins Publishers, New York, p. 81, 2021. Return to text.

- Oxnard, C., Fossils, Teeth and Sex: New perspectives on human evolution, Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, p. 227, 1987. Return to text.

- DeSilva, ref. 45, p. 130. Return to text.

- Line, P., Sahelanthropus tchadensis: Toumaï, chap. 12; in: Bergman, J., Line, P., Tomkins, J., and Biddle, D. (Eds.), Apes as Ancestors: Examining the claims about human evolution, BP Books, Tulsa, OK, pp. 157–168, 2020. Return to text.

- Callaway, E., Femur findings remain a secret, Nature 553:391–392, 2018. Return to text.

- Macchiarelli, R. et al., Nature and relationships of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, J. Human Evolution 149:102898, p. 7, 2020. Return to text.

- Macchiarelli et al., ref. 50, p. 9. Return to text.

- Marshall, M., The war over Toumaï’s femur, New Scientist 248(3309):17, 21 November 2020. Return to text.

- DeSilva, ref. 45, p. 65. Return to text.

- Line, ref. 48, p. 157. Return to text.

- Guy et al., Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad, researchsquare.com/article/rs-69453/v1, 9 September 2020 ǀ doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-69453/v1. Return to text.

- Hershkovitz et al., A Middle Pleistocene Homo from Nesher Ramla, Israel, Science 372(6549):1424, 1427, 2021. Return to text.

- Hershkovitz et al., ref. 56, p. 1424. Return to text.

- Hershkovitz et al., ref. 56, pp. 1426–1428. Return to text.

- Sáez, R., Nesher Ramla and the coexistence of diverse human groups in the Levantine corridor, nutcrackerman.com/2021/06/24/nesher-ramla-coexistencia-distintos-grupos-humanos-en-corredor-levantino, 24 June 2021. Return to text.

- Lahr, M.M., The complex landscape of recent human evolution, Science 372(6549):1395, 2021. Return to text.

- Hershkovitz et al., ref. 56, p. 1427. Return to text.

- Hershkovitz et al., ref. 56, pp. 1427–1428. Return to text.

- Zaidner et al., Middle Pleistocene Homo behavior and culture at 140,000 to 120,000 years ago and interactions with Homo sapiens, Science 372(6549):1433, 2021. Return to text.

- Bower, B., Israeli fossil finds reveal a new hominid group, Nesher Ramla Homo, sciencenews.org, 24 June 2021. Return to text.

- Ji, Q. et al., Late Middle Pleistocene Harbin cranium represents a new Homo species, The Innovation 2:100132, 2021. Return to text.

- AFP, ‘Dragon Man’: Scientists say new human species is our closest ancestor, weeklytimesnow.com.au, 26 June 2021. Return to text.

- Bower, B., ‘Dragon Man’ skull may help oust Neandertals as our closest ancient relative, sciencenews.org, 25 June 2021. Return to text.

- Gibbons, A., Stunning ‘Dragon Man’ skull may be an elusive Denisovan—or a new species of human, sciencenews.org, 25 June 2021. Return to text.

- Shao, Q. et al., Geochemical provenancing and direct dating of the Harbin archaic human cranium, The Innovation 2:100131, p. 1, 2021. Return to text.

- Ni, X. et al., Massive cranium from Harbin establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage in China, The Innovation 2:100130, p. 1, 2021. Return to text.

- Ni et al., ref. 70, p. 5. Return to text.

- Geggel, L., New human species ‘Dragon man’ may be our closest relative, livescience.com, 26 June 2021. Return to text.

- George, A., ‘Dragon Man’ claimed as new species of ancient human but doubts remain, newscientist.com, 25 June 2021. Return to text.

- Wei-Haas, M., ‘Dragon Man’ skull may be new species, shaking up human family tree, nationalgeographic.com, 26 June 2021. Return to text.

- Handwerk, B., A 146,000-Year-Old Fossil Dubbed ‘Dragon Man’ Might Be One of Our Closest Relatives, smithsonianmag.com, 25 June 2021. Return to text.

- Line, P., Homo heidelbergensis, chap. 17; in: Bergman, J., Line, P., Tomkins, J., and Biddle, D. (Eds.), Apes as Ancestors: Examining the claims about human evolution, BP Books, Tulsa, OK, pp. 316–317, 323, 2020. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.