Journal of Creation 35(2):91–97, August 2021

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

The ‘waters above’ do not surround all galaxies:

a critique of the ‘cosmic shell’ interpretation of Genesis 1:6–8

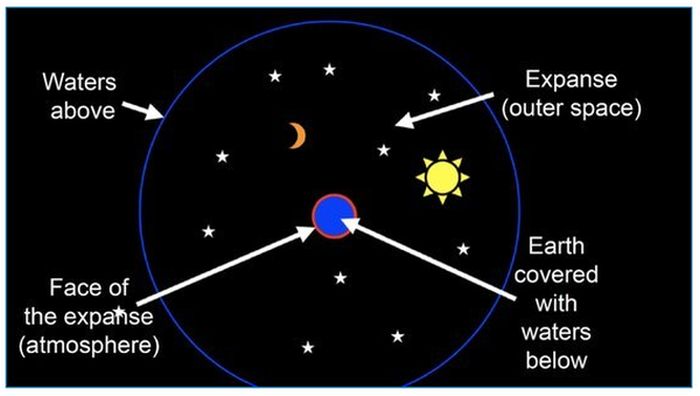

Many creationists believe that the waters God placed “above the expanse” on the second day of Creation Week depict waters surrounding the entire universe. But this ‘cosmic shell’ view faces several exegetical difficulties. Three problems are outlined, leading to a recommendation that the cosmic shell view be reconsidered.

Among Bible interpreters, there is a notable lack of consensus regarding the identity of “the waters that were above the expanse”, which God separated from “the waters that were under the expanse” on Day 2 of Creation Week (Genesis 1:7). In the Genesis account, the waters below are later given the name “Seas” (Genesis 1:10), but God does not name the waters above. To what do they refer? Many views have been offered, but most Bible readers subscribe to one of four positions which can be summarized using the following shorthand names: (1) a pre-Flood canopy, (2) a vaulted sea, (3) clouds, and (4) a cosmic shell.

In creationist circles, it was once popular to believe the first view—that the earth was originally surrounded by a vapour canopy which collapsed at the time of Noah’s Flood to produce its 40 days and nights of rain. This theory has fallen out of favour due to its numerous biblical and scientific problems.1,2 Creationists also rightly reject the second view, held by liberal scholars, that the biblical authors conceived of the waters above as a liquid ocean suspended over a flat earth, held back by a solid vault in the sky. This perspective is inconsistent with inerrancy, and it also has serious exegetical problems.3 My own view is that the waters above refer to clouds. This view will not be defended here other than indirectly by way of critiquing the fourth proposal—that the waters above refer to a shell of ice fragments or liquid water surrounding the entire universe. Though the cosmic shell view has become popular among contemporary creationists, it faces several challenges that require attention.

A summary of the cosmic shell view

While a form of the cosmic shell idea was advocated long ago by such historical figures as Martin Luther (figure 1), its modern incarnation was developed and popularized by creationist physicist Russell Humphreys.4 Similar views have been espoused by Faulkner and Mortenson.5,6 In Humphreys’ model, on Day 1 God initially created a giant sphere of liquid water which included the inchoate earth. The sphere is equated with the primordial ‘deep’ of Genesis 1:2 and its surface was “the face of the deep” over which the spirit of God hovered. On Day 2, God allegedly split this sphere into a much smaller inner sphere and a larger outer shell of water, leaving empty space in between. The inner sphere was to undergo further changes during Creation Week to become more like the earth as we know it, with its now familiar dry land, oceans, plants, and animals. Meanwhile, Humphreys proposed, God pushed the upper shell of ‘waters above’ outward so that the ‘expanse’ (raqiya‘) between the two bodies of water quickly grew to envelop all of what would become “interstellar space”.7 As the shell of upper waters rapidly receded from proto-Earth, it thinned to form a spherical halo (or cosmic shell) surrounding the entire universe, quickly reaching a size of at least 24 billion light-years in diameter.8 This shell need not have remained in a liquid state or as one contiguous body, according to Humphreys. He says that it may now be in the form of “a tenuous veil of ice particles, or perhaps broken up into planet-sized spheres of water with thick outer shells of ice.”8 Faulkner believes instead that the use of the Hebrew term ‘waters’ (mayim) indicates that they somehow managed to remain in a liquid state.9

Humphreys, Faulkner, and Mortenson all claim that the cosmic shell view is the most natural reading of the text. The waters above must be beyond the stars, they insist, because they were positioned “above the expanse” which was named “Heaven” on Day 2 (Genesis 1:7–8), and God set the stars “in” that very “expanse of the heavens” on Day 4 (Genesis 1:14–19). But it’s not so simple. Here are three exegetical reasons why the cosmic shell view should be reconsidered, and why the waters above need not have been placed beyond the stars.

The cosmic shell view is at odds with the creation account’s focus on known elements of the world and their relationship to humanity.

A careful reading of the creation account shows that it is concerned with letting readers know that God alone created the basic constituents of the world which were familiar to the ancients. It is also plainly concerned with mankind’s position and role within the created order. Why would esoteric materials hidden at the edge of the universe be discussed in such an account?

All of the other items that God created according to Genesis 1 were familiar to and had a known impact upon the original Israelite audience. Genesis describes in simple terms God’s creation of day and night; the land and seas; vegetation; the sun, moon, and stars; creatures that swim, fly, and walk; and mankind. All of these have important functions related to human beings. Land, sea, and sky were basic regions of the world that ancient Israelites could encounter. Celestial bodies with their daily cycle of light and dark were to serve as calendars, light sources, and more (vv. 14–15). Plants were given as food for man and beast (vv. 29–30). Animals of land, sea, and sky were to be ruled over by mankind (v. 28). By contrast with these familiar items and their relationships to humanity, any water billions of light-years from Earth could not have been observed by the ancients nor have had any relevance to daily life in the ancient Near East. If these were the ‘waters’ the author of Genesis had in mind, it is puzzling that they are mentioned in the text at all, let alone given the prominent attention they receive as a feature of Day 2.

Furthermore, there is no hint in Genesis 1 nor the rest of the Bible that God intended to reveal secrets about the largescale structure of the cosmos which could not be discovered apart from special revelation. The idea that God was giving the Israelites advanced scientific revelation—the inside scoop on water locked up at the furthest extremes of the cosmos—simply does not comport with the teaching purposes of the Genesis creation account.

The cosmic shell view cannot sustain its supposition that the term raqiya‘ (‘expanse’) retains a single rigid meaning throughout Genesis 1.

As mentioned, a key assertion of Humphreys, Faulkner, and Mortenson is that the ‘waters above’ must be higher than the stars. But the Bible nowhere says that the waters are above the stars. It only says that they are above the raqiya‘ (‘expanse’) that God made on Day 2. The idea that the waters are above the stars is an inference based on two factors. First, the sun, moon, and stars were set “in the expanse (raqiya‘) of the heavens” on Day 4 (Genesis 1:14–19). Second, it is argued that the term raqiya‘ retains a precise and fixed meaning throughout Genesis 1, permitting no variation between its occurrences on Days 2, 4, and 5.10 But if raqiya‘ has only one meaning throughout Genesis 1, this leads to a problem.

On Day 5, God created winged creatures to “fly above the earth across the expanse (raqiya‘) of the heavens” (Genesis 1:20). More literally, the Hebrew says that the birds fly “on the face of the expanse of the heavens”. Both Humphreys and Mortenson think this detail weighs in favour of their interpretation. Against those who would equate the expanse with the atmosphere, they point out that the birds are not said to be in the expanse, rather they are ‘al pene, “on the face” of it. Humphreys says, “the literal Hebrew doesn’t have ‘in the open expanse’. It doesn’t even have the preposition ‘in’. Instead it uses another preposition, לַע (‘al), which means ‘on, over, above’, but not ‘in’.”11 Mortenson similarly says, “The preposition al never means ‘in’.”12

Humphreys and Mortenson are correct that ‘al does not mean ‘in’. But they do not appreciate the significance of this fact for determining the location of the birds in Genesis 1:20, and thus the meaning of raqiya‘ in the context of Day 5. Oddly, after emphasizing the fact that the birds are not said to be in the expanse nor in its face, they place them there anyway.

According to Mortenson, “the raqiya‘ extends from the water on the surface of the earth to the waters above”, which he locates at the edge of the universe. But the “face of the expanse”, he claims, “is the relatively very thin inside perimeter or veneer of the raqiya‘ [which] we call today ‘the atmosphere’” (figure 2).13 Humphreys agrees, claiming:

“Birds can fly up to altitudes of 25,000 feet …, at which point they are above two-thirds of the atoms of the atmosphere. So most of the atmosphere is merely at the surface of the expanse. Therefore the expanse itself must be something much bigger—such as interstellar space” (figure 3).14

Is this really what the author of Genesis intended to convey, that the birds fly inside of the expanse’s face, which is a region of considerable thickness (at least 25,000 feet)—only thin by comparison to higher heavens? Not at all. This interpretation fails for three reasons.

It is doubtful that a ‘face’ refers to a layer of any thickness rather than a surface.

First, the biblical evidence does not support the idea that a ‘face’ describes an outer layer that itself contains some depth. In the Old Testament, the Hebrew term “face” (panim) often refers to a face belonging to a human, another creature, or God. But when referring to objects, it refers to a surface, facing side, facade, border, or edge. Frequently it refers to the surface of the earth or sea. But it can also refer to the visible surface of the full moon (Job 26:9), the sharp edge—or perhaps flat side—of an ax head (Ecclesiastes 10:10), the east side of the Jordan River (1 Kings 17:3), the flat top of a column (2 Chronicles 4:13), the front surface of the mercy seat (Leviticus 16:14), the facade of the temple (2 Chronicles 3:17), the eastern border of Egypt (1 Samuel 15:7), and the visual appearance of the city of Sodom from a distance (Genesis 18:16). In all cases, the ‘face’ would include the contours, if any, of the surface, but does not extend beneath the surface to refer to the outermost layer of an object. For example, the face of an apple would refer to an exterior side visible to an observer, not to the apple’s skin.

Some might allege that Job 41:13 provides a counterexample. The verse asks, regarding Leviathan, “Who can strip off the face of his garment?” (my translation). This obviously refers metaphorically to the creature’s impenetrable scales. But even here the face need not be identical with Leviathan’s ‘layer’ of scaly skin. The face could merely be the outer hard surface of his scaly skin. So there are no clear biblical examples where an object’s ‘face’ is a layer of any depth, let alone one that is 25,000 feet thick.

Mortenson claims that Scripture’s references to “the face of the earth” have in mind a layer with some depth. He says the phrase refers to a “perimeter or layer or veneer of the earth” which is still “very thin compared to the radius of the earth”.13 But he does not offer any exegesis to demonstrate that this is what the phrase means. He appears to believe it because he says the face is “where people, plants, and animals live (even those that live in the ground or deep in the oceans)”.13 But an examination of texts that speak of creatures on “the face of the earth” (or land, ground, field, etc.) shows they typically describe land animals, not sea creatures. Fish are usually said to be “in the water under the earth” rather than on its face (Exodus 20:4; Deuteronomy 4:18; 5:8).

One possible exception is Zephaniah 1:2–3, which seems to use a broader definition of ‘earth’ that includes the regions of the sea as well as the dry land. But even if “the face of the earth” does include oceanic realms in this passage, this would still be consistent with the ‘face’ referring only to the surface of the ground, not a layer of earth and seawater. The biblical writers knew that land extended beneath the sea (Job 38:16; Psalm 18:15; Jonah 2:5–6; Nahum 1:4), so fish “on the face of the earth” would mean those above the seafloor.

As for the burrowing creatures, they are implicitly included among the group described in Genesis 7:23, for example, as “every living thing that was on the face of the ground”. But if the face is a layer that encompasses their burrows, why aren’t these creatures said to be in the face of the ground rather than on it? Burrowers are grouped with those on the earth’s face because, first, burrowers spend some time above ground and, second, the text is making a generalization about the location of land-dwelling animals, not intending to pedantically describe every exceptional case. This is similar to the way God gave animals “every green plant for food” (Genesis 1:30) without meaning to exclude plants of other colours.

In sum, no passages clearly portray an object’s ‘face’ as a layer, so the proponents of the cosmic shell view have no sound basis for treating “the face of the expanse” in this way.

The original audience would not have considered the atmosphere to be a ‘thin’ veneer.

Even if the term ‘face’ could be used to describe a layer of some thickness, ancient Israelites did not have modern science to tell them that stars were vastly more distant than the heights achieved by birds and clouds, and the evidence we have suggests they did not think of the heavens in this way. In the Bible, clouds are frequently featured—more often than stars—as examples of extreme heights (Job 20:6; 22:12–14; 35:5; Psalm 36:5; 104:13; 108:4; Isaiah 14:14; Ezekiel 31:3, 10, 14). This is not to say that the Bible commits any error here, as no claim is made that stars are actually nearby. Scripture is silent about precisely how distant heavenly objects are. But it would be anachronistic to insist that the biblical author conceived of the starry heavens as so incredibly vast that, by comparison, the atmospheric region was merely a thin veneer. Here again, the cosmic shell view presumes that the Bible discloses advanced scientific insights—this time about the vastness of space. But there is no good reason to believe that the Israelites had this understanding. Thus, equating “the face of the expanse” with the region we call the atmosphere would have made no sense to them, so they must have understood the face to mean something else.

Birds are in front of the ‘face’, not inside it.

Even if the expanse’s face were a layer 25,000-feet thick, and even if the Israelites thought that the face was merely a veneer compared to the rest of the heavens, it would still be problematic to locate the birds inside the face of the expanse, because the expression ‘al pene in Genesis 1:20 demands that the birds are outside of this face, not within it. Other uses of the phrase show that it refers to a position of being on, above, or in front of something. In Genesis 1:2, for example, “the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.” In Genesis 6:1, “man began to multiply on the face of the land.” In Genesis 19:28, Abraham “looked down toward [literally, on the face of] Sodom and Gomorrah”. In all such cases, the subjects which are on or before the face are never positioned wholly inside it. They are outside of the face, either in contact with the surface, or situated opposite to it.

There are a few instances where objects partly penetrate a surface and are still described as “on the face”, but these are not exceptions to the rule. For example, Genesis 1:29 says that plants were “on the face of all the earth”, though their roots extended below the surface of the ground. Likewise, in Genesis 7:18, Noah’s Ark “floated on the face of the waters” even though some portion of it was submerged. In these instances, the idea is not that the objects were suspended within the face of the earth or the waters, because this would be inconsistent with the use of ‘al pene elsewhere. Rather, the expression means that the visible portion of these objects rose up from the surface. It’s only because they extended above the surface that they could be said to be “on the face”.

Hence, based on Scripture’s use of the phrase elsewhere, the birds which are ‘al pene in Genesis 1:20 must be outside (or at least extend outside) the face of the expanse. Humphreys and Mortenson place them entirely inside, so they cannot be correct. Faulkner is too vague on this point to critique.

A better way

The solution is to abandon the supposition that the ‘expanse’ must mean exactly the same thing throughout Genesis 1. The idea that the term ‘expanse’ can be flexible in meaning should not be surprising, since the expanse is coextensive with the ‘heavens’ (shamayim)—a term which is demonstrably flexible. Mortenson acknowledges this, calling shamayim an “imprecise word” which can refer to different aspects of the sky in different contexts.15 For example, wind can blow “in the heavens” (Psalm 78:26), referring to the area where birds fly, yet the clouds can also “cover the heavens” (Psalm 147:8), meaning they block from view the portion of the sky that is further away. The term shamayim can even switch meanings within a few verses, without warning. For instance, Genesis 6:7 calls birds creatures “of heaven”, but Genesis 6:17 classifies them as creatures “under heaven”. Birds can be described in both ways because the term ‘heaven’ conveys different concepts in the two instances.

Humphreys even admits that there are multiple ‘heavens’ in Genesis 1. He says:

“ … on day one God made a space, called the heavens, which contained a large body of water, the deep. On day two [H]e made the expanse, which He also called ‘heavens’, within the waters. Thus, there would be two heavens, the day-two heavens being a subset of the day-one heavens.”16

If so, there is no need to presume that the phrase “expanse of the heavens” always refers to the Day 2 heavens.

In the case of Genesis 1:20 (Day 5), the most natural way to understand the phrase, “the face of the expanse of the heavens”, is as a phenomenological description. This is because, as shown above, the face must be a facing side or a surface rather than a layer, and the birds are located on the near side of this face. The sky doesn’t literally have a ‘surface’, but, using the language of appearance, it is natural to refer to the sky’s opaque features apparent to a viewer as its ‘face’ (presenting side). So “the face of the expanse” refers to the appearance of the sky above as a background, just like the ‘face’ of Sodom that Abraham saw refers to its presenting side from his vantage point. The birds can fly ‘al—that is, in front of—this face without being in it because the face of the expanse is the visible backdrop, not the three-dimensional atmosphere.17 This interpretation is the only one consistent with the true meaning of the phrase ‘al pene as it is used throughout Scripture.

This precludes the expanse of Day 5 from being identical to the expanse of Day 2. The Day 2 expanse extends from the waters above down to the surface of what became the sea, so it must include the invisible airy space where birds fly.18 But on Day 5, the expanse clearly does not include the space where birds fly. The birds are outside of and in front of this expanse, so it must only refer to what is behind them.19

Once the expanse is acknowledged to have more than one meaning in Genesis 1, it can no longer be assumed that the waters above the expanse of Day 2 must also be above the expanse of Day 4. On Day 2, the upper waters could be clouds above the spacious region where birds fly—appropriately labelled “Heaven” (Genesis 1:8). But the Day 4 expanse could refer to the more distant part of the sky that appears to be blue during the day and populated by stars at night, no different perhaps to the Day 5 expanse. This variation in the meaning of the term ‘expanse’ is demanded by a careful investigation of its contextual usage, and such variation undermines any requirement that the ‘waters above’ be higher than the stars.

The cosmic shell view makes the ‘deep’ of Genesis 1:2 so vast that it threatens to undermine the contextual meaning of the terms ‘earth’ and ‘deep’.

Before the waters were separated on Day 2, they were previously united as one body on Day 1, when they were called “the deep” (Genesis 1:2). Outside of Genesis 1, the ‘deep’ (tehom) typically refers to seas as well as subterranean waters that can rise to the earth’s surface through springs. Another term that serves a similar purpose is ‘depths’ (metsolah), which is most commonly used to refer to deep seas. The ‘deep’ and plural ‘deeps’ or ‘depths’ are always treated as components of the ‘earth’ when the latter is defined broadly to encompass all regions under heaven, as opposed to mere dry land. For example, Psalm 148:7 says, “Praise the Lord from the earth, you great sea creatures and all deeps”. The deeps belong to the realm of Earth.

Was this also true of the deep when it was first created? Yes. In Genesis 1, the deep is clearly associated with the ‘earth’ made on the first day. This is implied by two important exegetical considerations. First, Genesis 1:1 is not a summary of the creation account or an “introductory encapsulation” as Faulkner asserts.20 It is the first creative act of Day 1. There are several strong reasons to regard it as the initial event, including the fact that in Hebrew there is a waw-conjunctive (translated “And” or “Now”) connecting verses 1 and 2. This is sandwiched between “the earth” at the end of verse 1 and the same term at the beginning of verse 2. Such a construction indicates that verse 2 is a circumstantial clause describing the state of the earth just mentioned, which involves an unfinished earth, not a completed one. Thus, verse 2 is not a description of conditions prior to any of the narrative’s events, but the state of affairs that resulted from verse 1.21

Also, Genesis 1 uses the classic formula for opening Hebrew narratives. It has a temporal clause (“In the beginning”) followed by a perfect verb (“created”) in verse 1, which regularly depicts the first event of a narrative. Next in the pattern comes a series of waw-consecutives (“and” prefixed to imperfect verbs). These describe subsequent events, exactly as found in Genesis 1 (“And said … And was … And saw … And

separated … ”).22,23

Furthermore, if verse 1 were an encapsulation of the whole week, then the earth and the deep would already have been present prior to the beginning of the account, without any explanation as to how they came to be. Ironically, if this were the case, the text would not actually describe the ultimate origin of the earth despite the claim of the encapsulation. No, the text means to say that God’s first act to kick off Day 1 was to create the regions of heaven and earth.24

The second consideration is that the phrase “the heavens and the earth” in Genesis 1:1 is a merism—combining two opposite extremes to refer to a whole. The phrase refers to the realms that comprise the entire (though as yet undeveloped) universe. It is not an exact synonym for ‘universe’ since the constituent parts are retained in the meaning.23 That is, the distinct regions of heaven and earth came into being with this first act of creation on Day 1, and they constitute the totality of physical realms. Also, because the context is about the first act of ex nihilo creation, here the expression would necessarily be inclusive of whatever contents these realms initially contained, such as the primordial waters discussed in the next verse.25

Verse 2 then comments on the state of the earth after its creation, and makes first mention of the ‘deep’. Since God’s creation of “the heavens and the earth” was the first creative act, and since these realms comprise the whole of creation, the deep must belong to one of them. Because verse 2 narrows the focus to the earth by itself, the deep in context belongs to the earth, not the heavens. Therefore, the term ‘earth’ in Genesis 1:1–2 does not refer merely to hard ground, but implicitly includes the waters of the deep. Even in its primordial state, the deep was created as a fixture of the earth.

The problem that then arises for the cosmic shell perspective is that this theory requires the deep to be so enormous that it becomes hard to see how it can be either part of or synonymous with the primitive earth. Consider how much water the cosmic shell view supposes was in the deep. The deep consisted of all of the ‘waters above’ and all of the ‘waters below’ prior to their separation. If the ‘waters above’ now encompass the entire three-dimensional universe—even as widely scattered ice fragments or liquid droplets—they must represent an enormous amount of mass.

Exactly how much space would the waters have occupied when they were originally combined on Day 1? Faulkner and Mortenson do not offer any specific estimates of the amount of material contained in the waters above or in the original deep. Mortenson cautions, “We have no biblical basis to say how much water is above the heaven or how thick that watery boundary is.”13 But we do know that the universe is extremely large, so even a thin, sparse cosmic shell would require a lot more water than is now present on the earth.

Admittedly, without specific numbers, Faulkner and Mortenson might be hard to pin down on this point. But Humphreys has speculated about the size of the initial deep, and his figures illustrate the difficulty.

Humphreys’ book, Starlight and Time, suggested the initial deep might have been a sphere “greater than 2 light-years in diameter”.26 In recent presentations, he has increased this to 20 light-years. Even the smaller figure of 2 light-years is mind-bogglingly huge. The diameter of today’s solar system, using the orbit of Pluto as its boundary, is merely 10 light-hours.

Humphreys does not try to claim that this enormous ball of water should be thought of as the early earth. No, he says, “The earth at this point is merely a formless, undefined region of water at the center of the deep, empty of inhabitant or feature.” 26 His presentations make it clear that the earth would be a tiny fraction of this material (figure 4). Planet Earth today has a diameter of about 1.35 x 10-9 light-years—more than a billion times smaller than Humphreys’ watery deep.

Given Humphreys’ view that the earth was tiny compared to the waters—absolutely dwarfed by an incomprehensibly large deep—it makes little sense to think of the deep as part of the primitive earth. The Bible presents the deep as a component of the earth, but Humphreys presents it as a collection of waters so vast that the earth virtually disappears inside it. If Humphreys’ depiction were correct, Genesis 1:1 should have said that God created the heavens and the deep, not the heavens and the earth.

I have not been able to ascertain Mortenson’s stance on the relationship between the primitive earth and the deep, but Faulkner takes a different view than Humphreys. He maintains that “the earth created at the beginning of Day One was a water mass”, which he equates with the deep.10 So, unlike Humphreys, Faulkner correctly believes that the primitive earth contained the entire deep. But if Faulkner joins Humphreys in thinking that the deep originally took up dramatically more space than planet Earth occupies today, problems remain.

Whereas Humphreys faces a challenge with the biblical conception of the ‘deep’, Faulkner faces a challenge with the biblical conception of the ‘earth’. For example, consider a scenario in which Faulkner’s water mass started off comparable in size to Humphreys’ ball, 2 light-years in diameter. In this case, it would not seem reasonable for Genesis 1:2 to describe this enormous object as “the earth”. Being composed of water is not the problem, as Faulkner reasonably argues that the term ‘earth’ can refer to “primordial matter that would become the earth as we know it now.”10 Yet, with a water mass of this size, the vast majority of it would not have served as raw materials which God transformed into our terrestrial planet. The bulk would instead have been swept to the edge of the cosmos. Faulkner’s so-called ‘earth’ would have been composed almost entirely of matter that became ‘cosmic shell’ and hardly any ‘earth’ at all.

It might be argued that one could rescue both Humphreys’ and Faulkner’s models from the above criticisms by postulating a cosmic shell which is dramatically less thick or less dense than Humphreys has supposed, so that far less water would be required in the original deep. However, it is not clear that any specific amount of water will alleviate the difficulty. For one thing, the universe could easily turn out to be much larger than our current estimates of its minimum size, exacerbating the problem. But even assuming a universe no larger than we can measure today, it may not be possible to find that ‘just right’ amount of water which is great enough to form a shell yet still minimal enough to fit on the earth. In my judgment, even a spherical water mass which was merely double our planet’s diameter is already too large to be faithful to the biblical terms ‘earth’ or ‘deep’. Yet if that same relatively small volume of water now surrounds the universe, it could only form a hopelessly meagre shell which would seem too insubstantial to be worthy of the description, “waters … above the expanse” (Genesis 1:7). If these assessments are correct, then no carefully chosen amount of water will allow the cosmic shell view to overcome this objection.

Conclusion

Although the cosmic shell view of the ‘waters above’ attempts to faithfully interpret the events of Day 2 of Creation Week, the problems highlighted here reveal that this proposal is not the most natural reading of Genesis 1. Hopefully, this contribution will encourage those who currently hold to the cosmic shell perspective to revise or abandon it.

References and notes

- Sarfati, J.D., The Genesis Account, Creation Book Publishers, Powder Springs, GA, pp. 158–160, 2015. Return to text.

- Humphreys, D.R., Starlight and Time, Master Books, Green Forest, AR, pp. 62–63, 1994. Return to text.

- Halley, K., The ‘windows of heaven’ are figurative, J. Creation 35(1):111–116, 2021. Return to text.

- Humphreys, ref. 2, pp. 32–36, 58–65. Return to text.

- Faulkner, D., The Created Cosmos: What the Bible reveals about astronomy, Master Books, Green Forest, AR, pp. 51–54, 2016. See also Faulkner, D.R., What were the waters of Day Two? answersingenesis.org, 29 January 2021. Return to text.

- Mortenson, T., The Firmament: What did God create on Day 2? ARJ 13:113–133, 2020. Return to text.

- Humphreys, ref. 2, p. 36. Return to text.

- Humphreys, D.R., New time dilation helps creation cosmology, J. Creation 22(3):84, December 2008. Return to text.

- Faulkner, ref. 5, pp. 52–53. Return to text.

- Faulkner, D.R., Thoughts on the rāqîa‘ and a possible explanation for the cosmic microwave background, ARJ 9:61–62, 2016. Return to text.

- Humphreys, ref. 2, p. 60. Return to text.

- Mortenson, ref. 6, p. 116. Return to text.

- Mortenson, ref. 6, p. 131. Return to text.

- Humphreys, ref. 2, p. 61. Return to text.

- Mortenson, ref. 6, p. 113. Return to text.

- Humphreys, ref. 2, p. 64. Return to text.

- The same concept is expressed in the New Testament, when Jesus referred to the ‘face’ (prosopon) of the sky, specifically its red colour and its cloud movements (Matthew 16:2–3; Luke 12:54–56). For Jesus, the ‘face of the sky’ is its phenomenal appearance. Return to text.

- This is where Kulikovsky’s view breaks down. He takes the waters above to be a cosmic shell but views the ‘face of the expanse’ not as the atmosphere but as “the boundary of interstellar space [which] is much further away than the bird.” So he does not believe the atmosphere is part of the raqiya‘. But the text describes only one expanse between the waters. There is no basis for introducing a second atmospheric expanse below the first. Kulikovsky, A.S., Creation, Fall, Restoration, Mentor, Fearn, Ross-shire, Scotland, pp. 129–132, 137, 2009. Return to text.

- We similarly switch between meanings of the term ‘sky’ and recognize the distinctions subconsciously with only subtle context clues. For instance, we might refer to trees that touch the sky, and elsewhere say that the sky is blue. Nobody should conclude from this that the trees must be in contact with the blue colour, because ‘sky’ is used differently in the two cases. The trees reach into the sky defined to include the invisible space just above us. But the blue sky does not refer to the nearby invisible air; it only refers to the visual appearance of the background further away. Return to text.

- Faulkner, ref. 5, p. 43. Return to text.

- Poythress, V.S., Interpreting Eden, Crossway, Wheaton, IL, pp. 291–321, 2019. See my review: Halley, K., Keen insights into Genesis 1–3 flawed by analogical days approach, J. Creation 33(3):14–18, 2019. Return to text.

- Sarfati, ref. 1, pp. 103–104. Return to text.

- Poythress, ref. 21. Return to text.

- Some say that this first event occurred prior to the first day, but Exodus 20:11 dispels this error. Return to text.

- In other contexts, the contents of the “heavens and earth” are distinguished from these realms (e.g. Genesis 2:1), but the phrase is a merism regardless of whether the totality includes only the realms or also their contents. Return to text.

- Humphreys, ref. 2, p. 32. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.