Journal of Creation 20(1):13–14, April 2006

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

A fossil is a fossil is a fossil. Right?

The recent findings of bio-molecules, soft-tissue blood vessels and blood cells in 65-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex fossil bones1 have caused geologists to re-evaluate the process of the preservation of fossils. After all, everyone knows that a fossil is an impression, cast, outline, or track of any animal or plant that is preserved in rock after the original organic material is transformed or removed.2 So, how can blood vessels and bio-molecules be found in fossils that are rock? Answer: a fossil does not need to be turned to stone to be a fossil.

The definition of fossil by the American Geological Institute begins, ‘The remains or traces of animals or plants which have been preserved by natural causes in the Earth’s crust.’3 There is nothing in this definition that requires transformation into rock. All that is important is that the fossil has been preserved. And preservation is a qualitative term that does not describe how the fossil was preserved. This is illustrated by Schweitzer in describing the fossil specimen MOR 555 [AKA, ‘Wankel T-rex’]:

‘An exceptionally well preserved specimen of the tyrannosaurid dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex shows little evidence of permineralization or other diagenetic effects.’ She further states, ‘Most fossils show signs of sediment infilling or secondary mineral deposition, but certain specimens can show little evidence of diagenetic change.’4

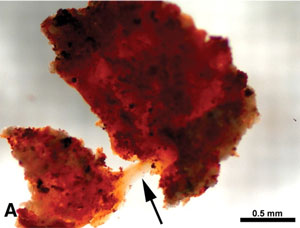

In other words, MOR 555 is a well preserved fossil with almost no mineral petrification, i.e. it is nearly pure bone (see figure 1)! This ‘65 million year old’ fossil is almost exactly the same today as it was when it was buried. So, if a fossil like MOR 555 can be a fossil without being turned to rock, then what makes a fossil a fossil?

We need to read the rest of the definition of fossil by the American Geological Institute. ‘The remains or traces of animals or plants which have been preserved by natural causes in the Earth’s crust exclusive of organisms which have been buried since the beginning of historic time.’3 It is more clearly stated as, ‘A remnant or trace of an organism of a past geologic age, such as a skeleton or leaf imprint, embedded and preserved in the earth’s crust.’5

So, according to this definition, a true fossil is something that has been preserved in some way or other from some ‘past geologic age before the beginning of historic time.’ It doesn’t matter if the material has or has not been turned to stone, i.e. petrified, but just that it was buried before the historic records of man!

Has this added caveat of deep time always been a part of the definition of fossil?

Let’s begin with a history of the use of the word fossil as paraphrased from Challinor’s A Dictionary of Geology:

The term ‘fossil’ (L. fossilis, dug up) was, as the word suggests, originally given to anything extracted from the earth or the rocks. It included minerals, all kinds of stony objects, and pieces of the rock itself, as well as the remains of organisms. ‘Fossilia’ in the wide sense and not, in fact, including organic remains, was used by Agricola in 1546. Gesner’s illustrated work on fossils included organic remains (1565). In Britain organic fossils were called ‘petrified shells’ (1665), ‘formed stones’ (1677), ‘fossil‑shells’ (1695), ‘figured stones’ (1699), ‘marine fossils’, ‘fossil fish teeth’ (1721), ‘native’ (minerals, &c.) and ‘extraneous’ (fossil shells, &c.) (1728). Owing, no doubt, to these various confusing usages, the term ‘fossil’ dropped out for a time, ‘petrification’ largely taking its place. The always appropriate ‘organic remains’ then became popular (1804/11), and was being used much later (1849 and following years). Meanwhile ‘fossil’ was again coming into use, but now for organic remains only, though usually with, or as, a qualifying adjective (1816, 1822). Already, however, the word by itself was beginning to be used. Parkinson (1804) remarks that ‘in the common language of those most conversant with these substances’ their nature ‘is conveyed by the substantive (“fossil”) alone’. Lamarck in France seems to have been the first definitely to restrict the term (1801, 1802). The substantive ‘fossil’, alone and exclusively for organic remains, became thoroughly established some twenty years later (1822).6

Up through 1948, fossils were defined as the remains of animals and plants or direct evidence of their presence preserved in the rocks of the earth. Yet, even then, the caveat of age is hinted at. While fossils were ‘evidences of animal or plant life in the rocks, such as petrified shells, skeletons, leaf and fern imprints, animals footprints and the like. It is chiefly by the aid of fossils that the age of the rock is determined.’7

As is typical of much of the debate about evolution and creation, the definition of fossil is not just descriptive but also interpretive since it includes the evolutionary interpretation of long ages. Therefore, in the evolutionists’ minds, every time creationists use the word fossil, they unwittingly concede the validity of the evolutionary paradigm. Furthermore, since creationists believe that most everything typically called a fossil was actually buried during Noah’s Flood, which occurred within historic time, then, from the creationists’ viewpoint, there is no such thing as a fossil, by that definition!

So what are creationists to do with the word fossil? It seems there are two choices. Either creationists can redefine fossil to fit the creationary viewpoint every time we use it, or invent a new word. A redefinition of fossil could be as simple as using just the first part of the American Geological Institute’s definition: The remains or traces of animals or plants which have been preserved by natural causes in the earth’s crust. The inconvenient part would be the need to state that redefinition in each creationary paper where fossil is used. The Latin clades fossio, meaning ‘catastrophic buried fossil’, has been suggested8 as a possible replacement. But anything new that is not as simple as the original may not catch on. In any case, the important thing to remember is a fossil may or may not be petrified. But we do not accept the evolutionary definition that a fossil is a biological remnant of a past geologic age before the history of mankind.

Blood and soft tissue in T. rex bone:

- 01 Dec 1993 Dinosaur bone blood cells found

- 01 Sep 1997 Sensational dinosaur blood report!

- 25 Mar 2002 Evolutionist questions CMI report—Have red blood cells really been found in T. rex fossils?

- 25 Mar 2005 Still soft and stretchy: Dinosaur soft tissue find—a stunning rebuttal of ‘millions of years’

- 28 Mar 2005 “Ostrich-osaurus” discovery?

- 16 May 2005 Squirming at the Squishosaur

- 01 Sep 2005 Dino soft tissue find

- 01 Dec 2005 Answering objections to creationist ‘dinosaur soft tissue’ age arguments

- 19 Jul 2006 ‘Schweitzer’s Dangerous Discovery’

- 16 Dec 2006 Why don’t they carbon-test dino fossils?

- 20 Apr 2007 Squishosaur scepticism squashed: Tests confirm proteins found in T. rex bones

- 02 Aug 2008 Doubting doubts about the Squishosaur

- 06 May 2009 Dinosaur soft tissue and protein—even more confirmation!

- 09 May 2009 Dino proteins and blood vessels: are they a big deal?

- 01 Dec 2009 More confirmation for dinosaur soft tissue and protein

- 11 Dec 2012 DNA and bone cells found in dinosaur bone

- 22 Jan 2013 Radiocarbon in dino bones

Other examples of soft tissue preservation in fossils:

- 01 Jun 1992 Fresh dinosaur bones found

- 01 Aug 1998 Exceptional soft-tissue preservation in a fossilised dinosaur

- 01 Dec 1998 Dinosaur bones—just how old are they really?

- 30 May 2000 ‘Sue’ the T. rex: another ‘missionary lizard’

- 01 Dec 2002 Feathered or furry dinosaurs? Soft tissue preservation

- 01 Apr 2004 Bone building: perfect protein (See paragraph six re osteocalcin in Iguanodon bones.)

- 01 Apr 2006 A fossil is a fossil is a fossil. Right?

- 07 Dec 2007 Hadrosaur hi-jinx: Will this find reveal more unfossilised soft tissues?

- 01 Jun 2008 The real ‘Jurassic Park’?

- 11 Nov 2009 Best ever find of soft tissue (muscle and blood) in a fossil

- 25 June 2013 Created or evolved?

References

- Schweitzer, M.H. et al., Soft-tissue vessels and cellular preservation in Tyrannosaurus rex, Science 307:1952–1955, 2005. Return to Text.

- Dictionary of geologic terms, 18 January 2006. Return to Text.

- Dictionary of Geological Terms, 2nd ed., American Geological Institute, 1960. Return to Text.

- Schweitzer, M.H. et al., Preservation of biomolecules in cancellous bone of Tyrannosaurus rex,J. Vertebrate Paleontology 17(2):349, 1997. Return to Text.

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed., Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000. Return to Text.

- Challinor, J., A Dictionary of Geology, 5th ed., University of Wales Press, 1978. Return to Text.

- Rice, C.M., Dictionary of Geologic Terms, Edwards Brothers, Inc, Ann Arbor, MI, 1948. Return to Text.

- Beverly Oard, personal communication. Return to Text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.