Fitness and ‘Reductive Evolution’

Herbert Spencer

Herbert SpencerEvolution comes with a lot of terminology. People sometimes struggle to understand some of the basic words used when talking about it. Even a phrase like “natural selection” is not necessarily easy to grasp, for, even if the term appears to be self-evident, “nature” cannot select anything. Since this phrase is the first thing people usually think of when they try to define evolution, the discussion starts out with some ambiguity. The phrase “survival of the fittest” was coined by a Darwin devotee, Herbert Spencer, and is often used as an alternate to natural selection. But it is not much better for clarity. For instance, what does “fitness” mean? Who are the most fit? Is it those who are the strongest, fastest, or smartest, or is it simply those lucky enough to have the most offspring? Actually, it is the latter. Evolutionary success is measured only by reproductive output—that is, did the organism have many or few offspring? You can be forgiven for not seeing that, because it is rare for a Darwinist to speak clearly on this matter. Most people, including most influential evolutionists, talk about survival, as if the length of life is important. An organism can be perfectly successful if it dies during a single reproductive episode (e.g. salmon) or if it survives to reproduce throughout a very long lifetime (e.g. oak trees). Thus, “survival” is irrelevant. It is not “survival” of the fittest, but “propagation” of the fittest that they are talking about. This is Darwin’s fault, initially, but evolutionists have been muddying the water ever since. We will show you several examples of how they do this below.

Fitness is defined in evolutionary biology as, “a relative measure of reproductive success of an organism in passing its genes to the next generation's gene pool.”1 Evolution can be reduced to this one metric: has fitness increased or decreased? But evolutionists often blur over how they measure fitness, meaning we are left trying to figure out how they came to their conclusions. For example, are they measuring how many offspring individuals with a certain trait have, or are they looking at a gene in a population and making assumptions about why that gene is so common? This is an effective sleight-of-hand, enabling them to control the terms of the debate.

This makes it possible for evolutionists to ‘move the goalposts’ any time creationists attempt to argue with them. Without a good definition of fitness or a straightforward way to measure it, the conversation devolves to, “You don’t understand evolution, therefore we win.” This is frustrating, to say the least.

Genetic Entropy

Dr John Sanford

Dr John SanfordThis tactic is frequently used, for example, in discussions about the reality of genetic entropy. Genetic entropy is a term coined by Dr. John Sanford to describe the gradual genetic decline of living things due to the accumulating effects of mutations.2 The discovery of the true impact that mutations have on life is the most serious challenge yet to the ‘Modern Synthesis’, also known as the ‘neo-Darwinian’ view of universal common descent. In fact, the entire theory of evolution can be said to be a car without an engine, since there is no known mechanism to account for the origin of genetic complexity as life supposedly evolved from bacteria to human beings. This points squarely in the direction of supernatural design, not undirected evolution, as the answer to the question of where life came from.

Fitness by fiat

We know that mutations happen, and we understand that most mutations are bad. So how does evolution work? One way evolutionists get around the problem is to ignore the discussion of mutations. They appeal to an increase in ‘fitness’ as a counter to any claim of genetic deterioration. If fitness has increased, they argue, then deterioration has not occurred. But in cases like sickle cell anemia, where the corruption of an important gene just happens to allow people to better survive malaria, children who carry the disease are more likely to live to adulthood. This is a bad change. The sickle cell trait is deleterious. It hurts people. But it helps them to survive. What do we do with this? Is it an example of natural selection? Yes. Is it good for the individual? Yes, but only if you live in places where malaria is present. Is it good for humanity? Not in the long run. “Fitness” in this case is subjective.

There are other cases where entire sets of genes have been lost in some species. They are able to survive because they have become fine-tuned to a specific environment. They have ‘adapted’ by becoming more specialized, but the original species could live in more diverse environments. Sometimes this is oxymoronically called ‘reductive evolution’. In this way, evolutionists never have to admit that genetic entropy is actually happening. But this is what natural selection does. It fine tunes a species to better exploit its environment. Since natural processes cannot ‘think’ ahead, the result is short-sighted. If the loss or corruption of a gene helps the species to survive better, it should be no surprise that this happens regularly. Species end up getting pigeonholed into finer and finer niches while at the same time losing the ability to survive well in the original environment. Natural selection goes the wrong way!

The Madeira coast

The Madeira coastTo cite a famous example: Darwin himself noted the prevalence of wingless beetles in windy areas of the Madeira islands off the coast of North Africa.3 Since winged beetles are more likely to be blown out to sea on a small, windy island, beetles with a mutation that reduces or removes their wings will be more likely to be around at reproduction time. This, in turn, is considered an ‘increase’ in fitness! Yet the information in the genome of the beetles has been corrupted, not improved, causing a feature to be lost. Darwinian language obscures that fact by claiming there has been an increase of fitness even though there has been a loss of something important. There are countless other similar examples of ‘reductive evolution’, meaning almost all examples of ‘evolution’ are running backwards.

In fact, a scientific paper written by two influential evolutionists (Yuri Wolf and Eugene Koonin) goes so far as to argue that the reduction of genetic material is the dominant mode of evolution!4 Using comparative genomics to assess changes in a variety of genomes over time, the authors conclude that, “[I]n many if not most lineages evolution is dominated by gene (and more generally, DNA) loss that occurs in a roughly clock-like manner … ” That is exactly what genetic entropy predicts!

Interestingly, the authors propose that evolution proceeds in two phases, with very short bursts of massive increases in genetic information followed by long periods of gradual decay. The assertion that bursts of increased complexity have happened at all, though, is entirely based upon the unquestioned presumption of evolution: “ … long-term increase in genome complexity (but not necessarily biological information density) is observed in various lineages, our own history (that is, evolution of vertebrates) being an excellent case in point.” The authors have no interest in questioning the evolutionary paradigm itself, but the actual operational science of their study shows only gradual decay. The authors do not even acknowledge, let alone attempt to solve, how or why these proposed sudden, massive increases of information would happen in the first place. The laws of probability would make any such chance occurrences completely untenable under naturalism.

What we see are countless examples of corruption and loss. What we do not see are examples of increasing complexity over time.5 Yet, in the evolutionary scenario the initial common ancestors of each major group must have been massively complex in order for the descendent species to contain the bits and pieces that remain. How about this for a better explanation: God created different ‘kinds’ which were full of genetic potential. After the Flood, as the members of those kinds spread out and got disconnected from each other, the individual subgroups were exposed to different environments. Each little group ‘adapted’, though ‘natural selection’, to its unique environment. This led to the development of the many ‘species’ we see on earth today. This was not through the Darwinian process of upward evolution but through a biblical process of separation and specialization.

An example of a spurious use of ‘fitness’ in recent viral research

One experiment being bandied about by anti-creationist skeptics in an attempt to disprove genetic entropy is from a paper entitled Evolution at a High Imposed Mutation Rate: Adaptation Obscures the Load in Phage T7. Here, they exposed a virus (T7) that infects the common bacterium E. coli to a mutagen. They wanted to see if they could drive the virus extinct by giving it a high mutation burden. We note that they did not control for the mutagen’s effect on the bacterium, which might explain some of their strange results. The paper begins by acknowledging,

“Evolution at high mutation rates is expected to reduce population fitness deterministically by the accumulation of deleterious mutations. A high enough rate should even cause extinction (lethal mutagenesis), a principle motivating the clinical use of mutagenic drugs to treat viral infections.”6

In plain English, this says that high mutation rates are bad, this might cause extinction, and this has been used to treat some viral infections (e.g. HIV). However, the authors claim their experimental results failed to conform to the expected decline in fitness. In fact, they claimed the opposite: an increase in ‘fitness’ over the course of the experiment, even going so far as to credit ‘adaptive evolution’:

“The main plausible explanation for the fitness increase is adaptive evolution, a process that lies outside the model.”(emphasis added.)

At first this may seem impressive to evolutionists, but what do the authors actually mean when they say fitness increased? And what is this “outside the model” thing? They define fitness as the ‘viral growth rate in the mutagenic environment’. This can only be a function of a combination of burst size (the amount of viral offspring per infected host cell) and lysis time (from infection to the time when the cell bursts to release the next generation of viruses). Yet, they recorded an 80% drop in ‘burst size’ over the course of their 200-generation experiment! How can the authors honestly claim that the strain was evolving upward in fitness when they lost 80% of their ability to successfully reproduce? If burst size went down, the only other way they could claim an increase in fitness would be for lysis time to go significantly down—enough to make up for that very steep drop in burst size. But no, the authors state:

“Lysis time was difficult to quantify precisely because phage release spanned several minutes … Lysis time (≈18 min) and adsorption rate (1.6 ± 0.2 × 10−9 ml/min) were largely unchanged from initial values, but the variance in lysis time was large enough to thwart accurate estimation of its mean (the data also do not allow a comparison of variances between initial and evolved populations). The main result is clearly the decline in average burst size, supporting a conclusion of a high load of deleterious mutations.”

You are not alone if you are confused by their explanation. In essence, they are saying that they don’t know what happened. Their measurements were all over the place (“high variance”), to the point where they could not draw conclusions (or, at least, they should not have!). So … if lysis time was largely unchanged, and the burst size went down by 80%, how exactly are they arriving at their claim of increased fitness? I (Paul Price) was so mystified by this that I personally contacted the corresponding author, Dr. J.J. Bull, to ask for his input on the matter. He responded:

"Having just looked at the paper again, it is the case that we did not have an easy explanation for the increase in fitness. The burst size went down, so if lysis time stayed the same (there was a big variance, complicating estimation of the mean), then fitness should have gone down. What we suggest as a possibility is that the means of burst size and lysis time should not be used to parameterize the fitness model when there are large variances."7

Well, at least we now know we aren’t crazy! It seems the authors were just as confused about this as we are. Fitness should go down, based on their results; why they claimed it went up still remains a mystery, as Dr. Bull did not exactly elaborate on that.

We also contacted John Sanford for his take on the experiment. He was crystal-clear that 200 generations is not long enough to see the effects of genetic entropy. It took the human H1N1 virus 90 years to go extinct (see below). In fact, it is possible to see local adaptation to a new environment while on the road to extinction, so even if fitness had technically increased during this short experiment, that would not have represented a challenge to genetic entropy.

This is a perfect example of how using a misleading definition of ‘fitness’ can mask the reality of genetic entropy, at least for those who are not careful enough to examine what they mean by it. This paper is inconclusive due to bad methodology; if anything, it supports the predictions of genetic entropy by showing a high load of deleterious mutations caused an 80% drop of burst size. It certainly cannot be legitimately used by evolutionists to challenge genetic entropy in any way.

Attempts to obscure genetic entropy in the H1N1 Virus

In 2012, I (Robert Carter) co-authored a peer-reviewed scientific paper with Dr. Sanford which dealt with the H1N1 influenza virus.8–10 The purpose of the paper was to see if we could find genetic entropy in action, and we did—the viral strain (the human version of H1N1) significantly degraded over time as a result of damaging mutations, eventually going extinct. It was already known that, after the viral outbreak started, the mortality rates continually went down. What we showed was that this correlated with an increased load of mutations in the viral genomes.

Mutation Accumulation in H1N1

Mutation Accumulation in H1N1We also measured something called ‘codon bias’. In genetics, 3-letter mini-codes within a gene tell the cell which amino acid to place in a protein. But since there are 64 possible 3-letter codes and only 20 amino acids, many of the 3-letter combinations code for the same amino acid. But different species prefer to use some codons over others. This is an important part of cellular design. If the cell uses one particular codon more often, there are all sorts of downstream changes that go along with it. For example, when a protein is manufactured, the gene for that protein is first turned into RNA. The RNA is then translated into a protein by an amazing machine called a ribosome. But different types of ribosomes are used for different classes of genes, because different genes preferentially use different codons. Codon choice is an important factor in cellular optimization. Influenza is a virus that infects waterfowl. It usually does not cause disease, and one would expect it to be fine-tuned to work in the genome of, say, a duck. Unexpectedly, after jumping to pigs and people about 100 years ago, the viruses became less adapted to the human genome over time. Their codon usage was approaching ‘random’. The viruses got worse over time at interacting with human DNA, meaning they were probably reproducing more slowly in the host. All of this fits together to show that the influenza virus succumbed to genetic entropy.

While there has been no peer-reviewed, scientific attempt to attack the validity of this paper to date (and in fact it has been cited several times by other scientists in the field), some online skeptics wish to throw stones at the paper and debate its accuracy. The main objection seems to be founded on yet another of these attempts to move the goalposts using the term ‘fitness’. Since viruses sometimes are able to propagate more effectively when they do not kill their hosts (leaving more time for the host to spread more viruses around), evolutionists usually say that viruses that are less lethal are more fit.11 Therefore, they claim, showing that the mortality rates dropped over time is actually showing an increase in fitness (adaptive evolution), rather than genetic entropy.

What’s wrong with that analysis? Simply this: in humans the influenza virus is a parasitic machine with one and only one function: making replicas of themselves using the hijacked equipment of their host’s cells. They do not ‘know’ anything, including whether or not they are going to kill their host and stop transmission from continuing. The only objective factor here, when it comes to the virus, is simply how many viruses are being produced, and how quickly. A virus with a large burst size creates more viruses per infected cell; a virus with a fast burst time is reproducing more quickly. The infected host will attempt to fight off the viral infection with the immune system; of course, if the virus outpaces the immune system of the host, the host can die.12 Conversely, a virus that is reproducing more slowly or less efficiently will be much less likely to overwhelm and kill the host. We can therefore see that we should expect to see an inverse correlation between mortality rates and the virus’ ability to replicate—as the virus reproduces less efficiently, mortality rates will go down. But the virus only has so much time to propagate to another individual before the host’s immune system kills it off. There is a short window of only a few days and any virus that reproduces slowly might fail to propagate to another host. If the virus is ‘less lethal’ because it grows more slowly, it is also more likely to be killed before it can spread. This is a contradiction in the evolutionary claims.

While it is arguably correct to say that certain viruses are able to maximize their spread by not killing their host, that explanation does not work in the case of influenza, since most deaths from influenza happen after the contagious period of the infection has already subsided—often from secondary infections like pneumonia.13 For the flu virus, the best way to spread is to reproduce as much and as quickly as possible; that is also likely to be much more deadly to those it infects. This is not true for HIV, because it evades the hosts immune system by hiding in white blood cells. It is also not true of Ebola, for it remains infectious even after the host dies. These three viruses all have different reproductive strategies. Would Ebola do better if it became less deadly? Maybe, but this would happen through genetic decay. As its systems became compromised, theoretically it could grow more slowly and infect more people by not killing the host as quickly. But just as with all the other examples of 'reductive evolution' we've shown thus far, this would be an example of decay (loss of function). It would tell us nothing about the origin of the virus (see box at bottom).

In the case of human H1N1, the fact that the viruses became less deadly shows they likely reproduced less within the host, and because viruses are replication machines, this likely means that the machinery degraded.14 That is a decline in functionality, which is consistent with genetic entropy.

What should we focus on instead of fitness?

In a recent lecture given at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, Dr Sanford noted that defining fitness in terms only of reproduction is a circular argument. He suggested instead that fitness be defined in terms of real traits and abilities like intelligence or strength or longevity.15 In other words, does the organism appear to be getting healthier over time, or weaker? Genetic entropy is not really directly about reproduction—it is about the decline of information in the genome. We should expect that as our genes are damaged, various physical traits would begin to decline as a result of this damage, and this decline will at first be more noticeable than any possible reduction of the ability to reproduce (this is especially true in humans, since we have advanced modern medicine to help us).

Conclusion

Only when we insist that the terms of the debate be fair and accurate will we have any chance to clearly communicate the truth of creation and the bankruptcy of Darwinism to the world at large. As we have undertaken to demonstrate here, evolutionists have been guilty of hiding behind the misleading use of the term ‘fitness’; it is now time for honest scientists to adopt a more realistic, objective look at the parameters of life. When one does this, the picture is bleak. We are all dying a slow death of genetic decay. Our hope is not in future scientific advances; it is in the Creator Himself, who has promised to, one day, restore this creation to its former glory, and he intends for us to enjoy that New Creation with Him for eternity. May that day come quickly!

The origin of viruses

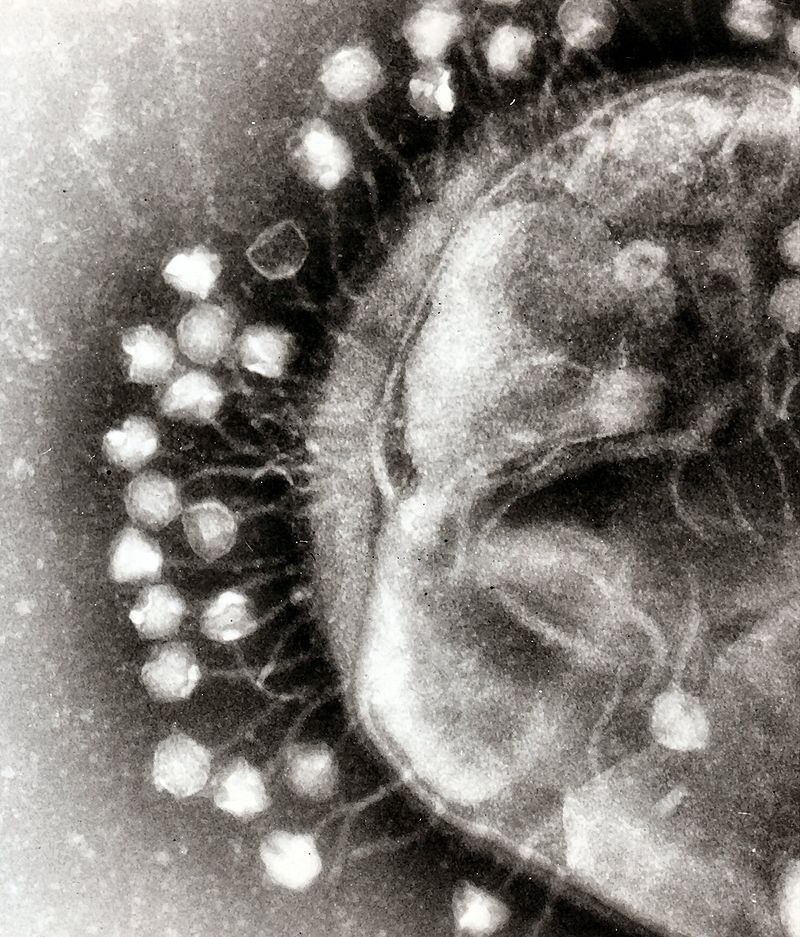

Viruses attached to a bacterium

Viruses attached to a bacteriumSince the discovery of viruses in 1892 (and their first visualization in 1940 by the newly-invented electron microscope), evolutionists have been using them as an argument against creation. From the large portion of the human genome that supposedly derives from viruses, to the lethal nature of the viruses discussed at length in this article, the virus has been a weapon used to discredit creation and the Creator. Some tough questions arise when dealing with the subject. For example, did God create these deadly pathogens? If so, what does that say about the nature of God? Or maybe they evolved. If so, what does that say about the history of the Bible?

We have addressed questions like this many times over the years—starting with an article simply titled “Viruses” by Dr. Carl Wieland way back in 1979 in the early years of Creation Magazine. Twenty years later, Dr. Jerry Bergman addressed the question, “Did God Make Pathogenic Viruses?” We have laid out arguments in an article titled Biological View of Viruses: Creation vs Evolution. We have assessed the phylogenetic relationships of several virus families, like the nucleoplasmic large DNA viruses, and discussed the enigmatic pandoraviruses that are a strong challenge to evolutionary theory. In essence, we are aware of the challenges and have been addressing them.

Yet many people are confused by the subject. The presence of viruses within creation looks like a challenge to what we believe. But what if we told you that most viruses are beneficial? This is true! Did you know there are more viruses in your gut than there are bacteria? In fact, viruses regulate the number and type of bacteria living there. They are an important part of a very beneficial relationship and without them we would die. There are also more viruses in the ocean than there are bacteria, for similar reasons and with similar results. From this, we can see that many viruses fit perfectly within a creation mindset.

But what about pathogenic viruses? These are the product of the Fall. Once sin and death came into the world—once corruption was the rule—it may have been only a simple step for an originally-designed beneficial virus to change. For instance, the influenza virus does not usually cause disease in their host species. However, when it jumps to pigs and people, it burns like wildfire because we do not have the natural regulatory mechanisms that aquatic waterfowl apparently do. True, flu strains sometimes arise that are very, very bad for birds. But this might be akin to cancer: a loss of control of cellular reproduction leads to tumor growth. This does not mean that cancer was an original condition. In the same way, many pathogenic viruses may have arisen through loss of control. They do not need to “evolve”. The system for which they were designed just needs to break.

Warren Shipton did a masterful job explaining the origin of pathogenic viruses from a creation perspective. It turns out that the cell does many of the things viruses do, including making viral-like coats and packing them with RNA or DNA. It is quite possible that many viruses are escaped systems originally designed by God.

Finally, viral-like sequences in the human genome show strong evidence of design. They are an important part of cellular information and control many different processes. See Large-Scale Function for ‘Endogenous Retroviruses’ by Shaun Doyle.

References and notes

- Darwinian fitness, Biology Online Dictionary, biology-online.org, accessed 27 November 2018. Return to text.

- Sanford, J., Genetic Entropy and the Mystery of the Genome, FMS publications, 2005. Return to text.

- Darwin, C., The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, London: John Murray, 1859, pp. 176–177. Return to text.

- Wolf, Y. and Koonin, E., Genome reduction as the dominant mode of evolution, Bioessays 35(9):829–37, 2013; doi.org/10.1002/bies.201300037. Return to text.

- But be careful with the outdated “no new information” argument. See Carter, R.W., Can mutations create new information? J. Creation 25(2):92–98, 2011. Return to text.

- Springman, R., Keller, T., Molineux, I., and Bull, J., Evolution at a High Imposed Mutation Rate: Adaptation Obscures the Load in Phage T7, Genetics 184:(1):221–232, 2010; doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.108803. Return to text.

- Personal email communication from Dr. J.J. Bull to Paul Price. Return to text.

- Carter R., and Sanford J., A new look at an old virus: patterns of mutation accumulation in the human H1N1 influenza virus since 1918, Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 9:42, 2012. doi:10.1186/1742-4682-9-42. Return to text.

- Carter, R., More evidence for the reality of genetic entropy, J. Creation 28 91):16–17, 2014. Return to text.

- Carter, R., More evidence for the reality of genetic entropy: Update, in press, 2019. Return to text.

- Evolution from a virus’s view, evolution.berkeley.edu, December 2007. Return to text.

- Edmonds, M., What is a virus, and how does it become a danger to human life?, science.howstuffworks.com, accessed 28 November 2018. Return to text.

- O’Rourke, K., Demystifying Secondary Bacterial Pneumonia, asm.org, 9 August 2016. Return to text.

- The paper addresses the possible objection that herd immunity or advances in medicine could have accounted for the decline in mortality we witnessed. Since the decline was witnessed several times as new strains emerged from 1918 through 1968, we can see that those outside factors were not significant. Return to text.

- Sanford, J., NIH Presentation – Mutation Accumulation: Is it a Serious Health Risk? youtube.com/watch?v=eqIjnol9uh8, 12 November 2018. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.